Reconstructing a lost object: can you identify this component in Alexander Graham Bell's 1874 ear phonautograph?

The ear phonautograph was a macabre instrument. It was built by Alexander Graham Bell and Clarence J. Blake in 1874, and used a surgically-removed human ear—a skull fragment, ear canal, ear drum, and ossicle bones—to visually “write” sound waves.

It worked like this: the surgically-removed ear was first attached to the top bracket of the instrument by a bolt driven through the skull fragment. It was then tightened in place with a thumbscrew. When a user spoke into the mouthpiece, located behind the ear, the sound waves produced by their speech would travel down through the mouthpiece and into the exposed canal of the ear. As these sound waves collided with the sensitive ear drum inside the ear canal, they would set off a chain reaction: the ear drum would vibrate first, followed by the ossicle bones, and then finally a small piece of straw—called a stylus—that had been attached to the final bone. When a piece of glass coated with a thin layer of black soot was pulled quickly underneath the ear, the vibrating stylus would then etch or “write” the shape of the vibrations onto the surface of the glass.

The name "phonautograph" comes from phono (sound) and autograph (write/sign). By turning invisible sound waves into visible “sound autographs,” it was thought that sound and speech would be easier to study and understand.

The ear phonautograph is an object of much historical significance. Most famously, it gave Alexander Graham Bell the technical insight he needed to patent the telephone in 1876—a fact he and Clarence J. Blake testified to in court.

The ear phonautograph also sheds light on the darker sides of this achievement. It’s less widely known, for example, that this instrument was designed as a speech training tool for the deaf. Bell hoped the ear phonautograph would lend support for his (highly problematic) belief that oralism—speech training and lip-reading—should be promoted over sign language. Bell and Blake also never revealed from whom, or on what basis, they acquired the human ear they used to create their phonautograph. This raises serious ethical questions about how they employed human remains as a technical component in the instrument.

Despite the ear phonautograph’s significance, no one has reported seeing the instrument in more than a century. Today, it is believed lost to history. That’s why, in 2016, I initiated a project to reconstruct it. By physically recreating the 1874 ear phonautograph, using a 3D-printed ear in place of the real thing, I hoped our museum could revisit this history and contribute to important conversations about the origins, politics, and legacy of Bell’s early work. We finished our first prototype in 2017, and have since been looking at ways to improve it.

To learn more about the ear phonautograph, you can read my full-length article on the reconstruction project here and a research award profile by the Canadian Museums Association here. You can also see the reconstruction in person by visiting the Canada Science and Technology Museum’s Sound by Design exhibition.

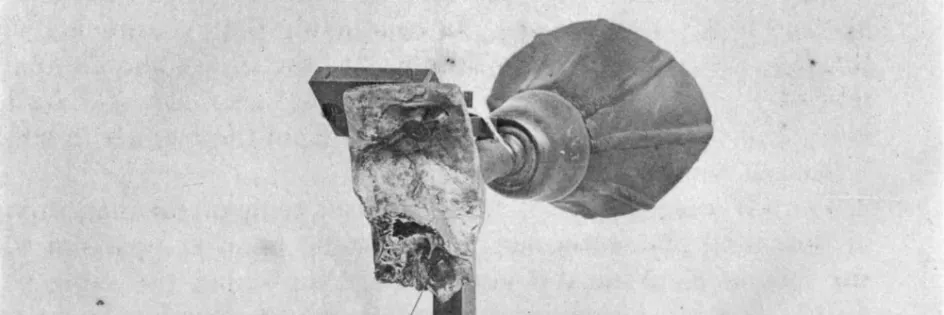

One particular challenge, which I’d like your help with today, is identifying a component that has so far remained a mystery to us: the ear phonautograph’s oddly-shaped mouthpiece (see Image 1).

While we do know what it does, we have no idea what it’s made of, where it came from, or why Bell and Blake would have chosen this mouthpiece over other possible designs.

Image 1: Mouthpiece of the 1874 ear phonautograph. We’re investigating what it was made of and where it might have come from.

The mouthpiece is a significant component in the ear phonautograph. It is here where users of the instrument would speak, and where their speech would be funneled into the surgically-removed human ear.

The material of the mouthpiece was no doubt carefully considered by Bell and Blake. It was critical because the sounds of the voice needed to be transmitted, with strength and little interference, directly into the ear canal to ensure the clearest and most accurate possible etching.

Unfortunately, neither Bell nor Blake recorded their choice of material for the benefit of future researchers, leaving it up to us—those future researchers they never anticipated—to guess.

And our guesses, so far, have left us no closer to solving the mystery.

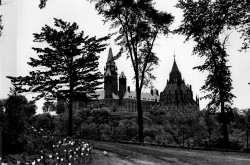

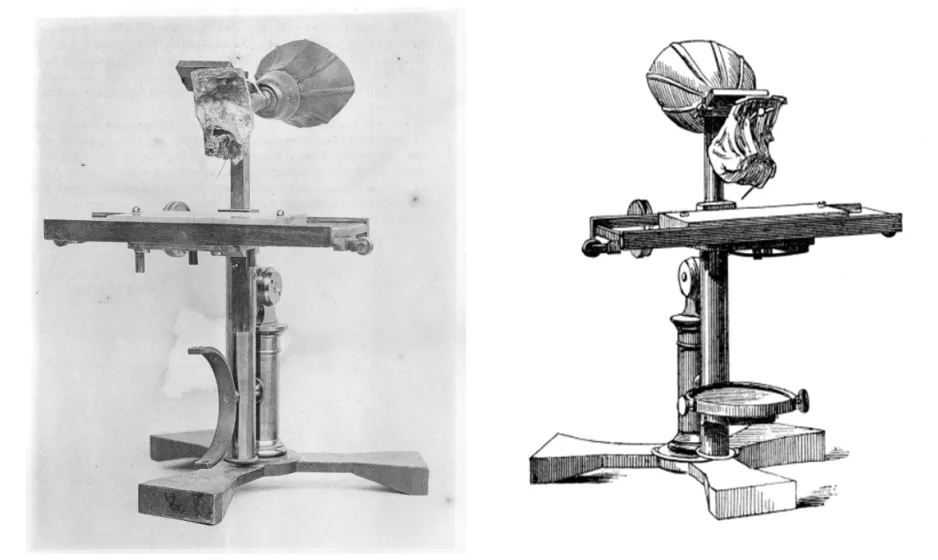

When looking at the two verifiable images of the original instrument we know to exist—one black-and-white photograph (Image 2) and one sketch (Image 3)—it’s difficult to determine what material the mouthpiece might have been made of, or where it might have come from.

Image 2 (left): The only known photograph of the ear phonautograph, published by Blake in 1876.

Image 3 (right): A line drawing of the ear phonautograph, published by Bell in 1877.

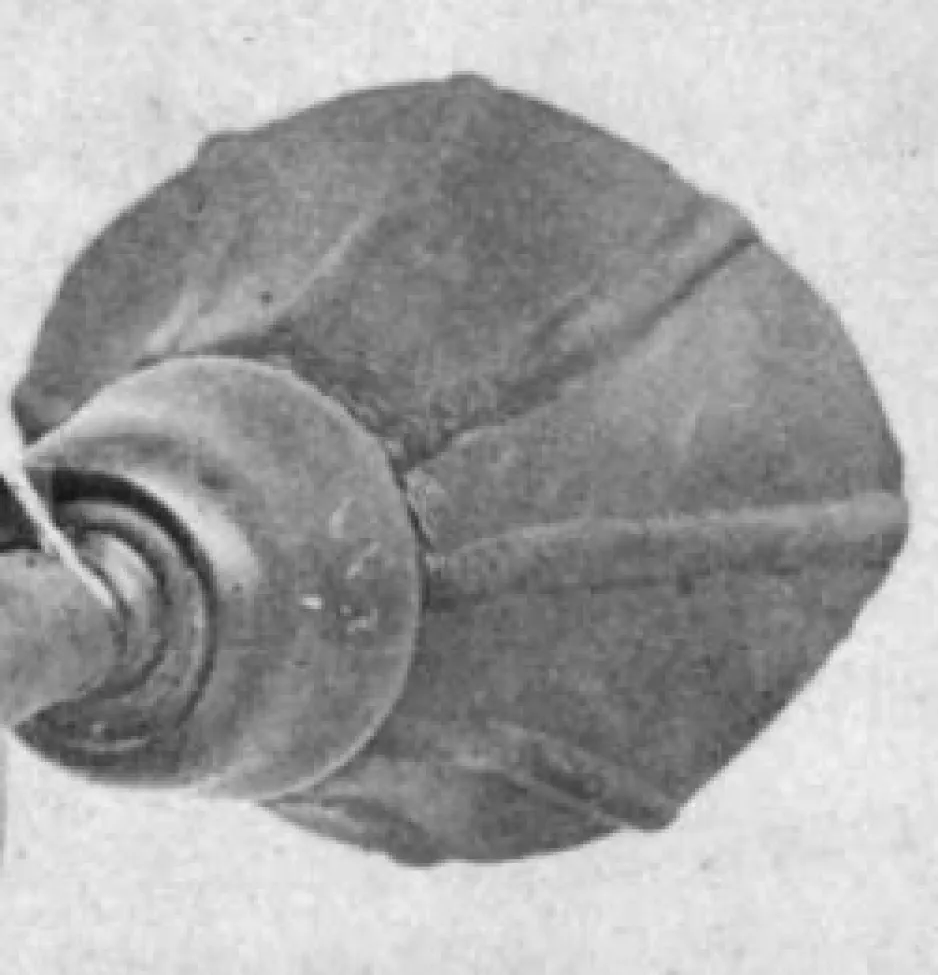

For our first prototype (Image 4), we experimented with a metal mouthpiece. After welding strips of brass together, however, we realized the ribbed look and texture/scale wasn’t a good match to the original. By comparing our finished prototype to the two images above, we determined the mouthpiece likely would have been made of leather, rubber, or some other more pliable material. But what material might that be, exactly? We’re still not sure.

Image 4: Our first prototype of the ear phonautograph, fabricated by Denis Larouche, with a mouthpiece made of metal.

Based on a colleague’s compelling recommendation to look into rugby ball bladders from the period (1870s), we launched an investigation to see what other objects or materials might be a better match for the look and texture of the ear phonautograph's original mouthpiece.

Here are some of the objects a member of our research team, Kate Jordan, turned up in her search—none of which yet appears to be the exact match we’re looking for. I will paraphrase from her findings:

Bladder for a ball (animal bladder, intestine): While the historical period lines up, internal organs (bladders, intestine sections, lungs, stomachs) are the incorrect shape. They don’t appear to have pronounced ribs or ridges, as does the surface of the 1874 mouthpiece.

Bladder for a ball (India rubber): Innertubes for balls were generally made of one piece of rubber and inflated with a hand or foot pump. No instances of sewn balls were uncovered, though it’s not beyond the realm of possibility that balls could have been made with separate pieces of rubbed stitched together and sealed (which would explain the outward-facing ridges). More research on rubber seaming and sealing methods in the 1870s could be worthwhile, but we’ve uncovered no promising leads so far.

Leather shell for a ball: The ridges on a ball typically go inwards at their seams, rather that protrude outwards, so no matches have yet been found for the ribbed surface of the mouthpiece.

Dictaphone mouthpieces: While used for a similar purpose—directing the voice into a sound-etching apparatus—the Dictaphone and similar technologies came after 1874. A variety of materials were used in these mouthpieces, from vulcanized rubber and Bakelite to glass and brass, but none appear to have a ribbed surface. As such, they offer little insight into the ear phonautograph mouthpiece’s materials or design.

Speaking tube: During our investigation, we uncovered a quote by Bell made during legal proceedings about the 1876 telephone patent in which he states that he had built other phonautographs (which didn’t use human ears) prior to the ear phonautograph. All of these previous instruments, he claims, “used a rubber tube, with a mouthpiece similar to those employed in speaking tubes.” While “similar to” could mean many things, and while he wasn’t referring specifically to the ear phonautograph in this quote, we decided to look into speaking tubes further. We uncovered several types—marine, domestic/residential, and those used as an early form of hearing aid—but none was a match for the ear phonautograph. Some, like marine speaking tubes, were made of brass or canvas; others, like domestic/residential and hearing aid speaking tubes, were made of brass, vulcanized rubber, Bakelite, or gutta percha (rubber). Most had a smooth, polished surface, in contrast to the ear phonautograph’s seemingly matte finish, and none had the latter’s prominent ridges.

Gas, anaesthesia, or vapour masks: Gas masks weren’t yet available in 1874, so they can be discounted, and anaesthesia masks typically had a much different shape/style (cloth stretched over a wire frame). Some vaporizers from the period used rubber mouthpieces, but these were more “fanned out” in shape than the ear phonautograph mouthpiece and didn't have any apparent ridges.

Plunger: None of the historical plungers we could locate were of the right shape. The ear phonautograph mouthpiece opens outward at the edges, possibly to form a comfortable seal around the speaker’s mouth. By contrast, plungers curve inwards as a means to create suction.

Funnel: The idea that a funnel for liquid could be repurposed as a funnel for sound was compelling, though we were unable to find any funnels that were a match in either materials or style.

Microscope eyepiece: While this might seem an odd choice, it was actually among the most obvious avenues for us to pursue. This is because we discovered, during the broader reconstruction project, that the ear phonautograph was actually built on a pre-existing microscope base. Could the eyepiece, which was dismantled to make way for the instrument’s sound-writing components, have been somehow repurposed to function as a mouthpiece? Unfortunately, no evidence of any broad eyepieces that would match the style of the ear phonautograph mouthpiece was uncovered in our search.

Oilcloth: Oilcloth is a light cotton canvas that is boiled in linseed oil for a few days before being hung to dry. Once dried, it stiffens into a waterproof material capable of retaining a pre-determined shape. Seams were often waterproofed by another layer of cloth, but could also be waterproofed along their seams with wax or pitch, leading to ridges not unlike the ridges seen on the phonautograph. While no evidence of similarly-shaped oilcloth mouthpieces was found, it’s plausible Bell or Blake could have created a bespoke design themselves. The technology would have been well-known and widely available at the time. That said, the process of creating oilcloth typically produced a much thinner membrane than is suggested in the photograph of the ear phonautograph. So if oilcloth was used, it’s likely it would have been made using an experimental, non-standard method.

So that’s where we’re at. After much brainstorming and researching, the mystery of the ear phonautograph mouthpiece remains.

What material was it actually made of? Why the strange “ribbed” surface? Was it custom-made by Bell and Blake, or borrowed from another instrument? If borrowed, where might it have come from?

If you have any thoughts or suggestions, we’d love to hear them. You can reach me directly on Twitter by following this link.

In the meantime, here’s a photograph of our updated version of the ear phonautograph (Image 5), with a more visually appropriate rubber mouthpiece. We’re looking forward to learning of any new insights or ideas it inspires in you.

Image 5: The revised ear phonautograph reconstruction with a mouthpiece made of rubber. Fabricated by Denis Larouche.