There and back again, a Delta’s long journey

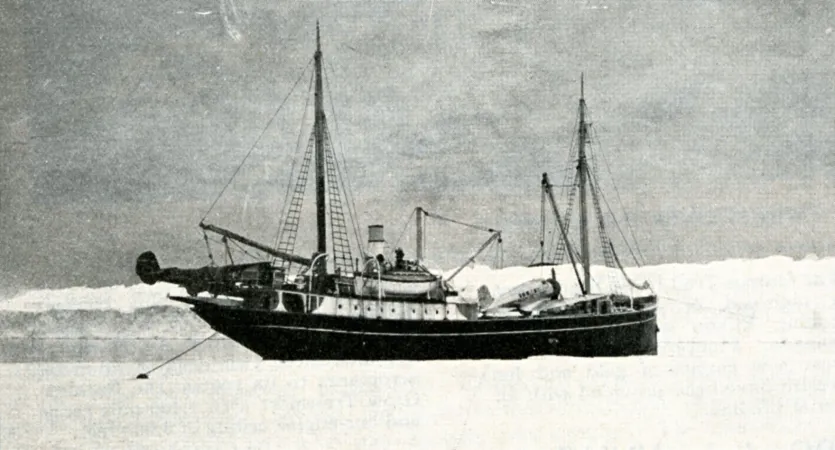

Greetings, he who has spent a great deal of time over a keyboard salutes you. While I realise that spring is in the air, up here, did you stop for a moment to think about the people currently living in Antarctica, for whom the month of May is a harbinger of winter? And yes, my reading friend, as the caption of the photo above, found in the May 1939 of the Canadian aviation monthly Canadian Aviation, states all too clearly, our topic of the week has to do with the land at the bottom of the world, Antarctica.

This isolated and dangerous land fascinated quite a few individuals, both would be explorers and seasoned explorers, during the 1920s and 1930s. One of these individuals was a well off American by the name of Lincoln Ellsworth. And yes, he was indeed mentioned in a March 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Ellsworth began to plan an Antarctic expedition in the early 1930s, in cooperation with a well known Australian explorer, geographer, ornithologist, photographer and pilot, Sir Hubert George Wilkins. His goal was nothing if not ambitious. Although not a pilot himself, Ellsworth wanted to make the first flight across Antarctica. As a first step, Wilkins bought a fishing vessel in Norway which, once refitted, became the base ship Wyatt Earp. Ellsworth, it seemed, admired Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp, a Wild West gambler, gunman, buffalo hunter, lawman and saloon operator. Most members of the expedition, including the pilot, Bernt Balchen, were Scandinavians, Norwegians from the looks of it. An important, if non human member of the expedition was the Polar Star, a Northrop Gamma skiplane that Northrop Corporation, a newly created American aircraft maker, had specially equipped.

The privately funded Ellsworth Wilkins expedition left Norway in July 1933. After some time spent in New Zealand, it sailed toward Antarctica in December. The Wyatt Earp moored near the edge of the ice in January 1934. Three days later, Balchen and Ellsworth flight tested the Polar Star. The following morning, heavy swells fractured the ice where the aircraft stood. The skis of the Polar Star were broken and a wing was bent. Unable to make repairs on site, the members of the Ellsworth Wilkins expedition had to call it quits, for the moment.

Ellsworth and Wilkins left New Zealand in September 1934, aboard the Wyatt Earp. The privately funded expedition reached its destination in mid October. By the end of that month, the Polar Star was ready for testing. A crucial part of the engine snapped. While Ellsworth, Balchen and few others stayed behind, in an abandoned whaling station, Wilkins and the crew of the Wyatt Earp sailed to Chile to pick up the needed part, flown in by Pan American-Grace Airways Incorporated, a joint venture created by Pan American World Airways Incorporated and Grace Shipping Company, a subsidiary of W.R. Grace & Company.

Wilkins and the crew of the Wyatt Earp were back in Antarctica by mid November. The Polar Star was ready for testing 2 or so weeks later. By then, so much snow had melted that no flight could be attempted. The aircraft was then loaded back onto the ship, which sailed south in search of a new base of operation. None was found. The members of the Ellsworth Wilkins expedition called it quits in late January 1935, for the moment.

You will remember, of course, that Pan American World Airways was mentioned in a November 2017 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Did you know that, in 1941, Balchen played a crucial role in the history of the first bushplane completely designed in Canada? Busy with the production of the North American Harvard advanced training aircraft for the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), Noorduyn Aviation Limited of Cartierville, Québec, considered closing the assembly line of its Norseman. Balchen, then working for the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), got 6 Norsemans destined for the RCAF to establish a military aircraft ferry route between North America and the United Kingdom, via Greenland. These aircraft proved so effective that the USAAF contacted Noorduyn Aviation after the United States entered the war in December 1941. They signed contracts totalling ultimately 720 slightly modified C-64 / UC-64 Norseman. This was the first time that the armed forces of a foreign country had ordered a Canadian aircraft.

Better yet, in early 1944, fearing delays in delivery, the USAAF asked the American company Aeronca Aircraft Corporation to manufacture 600 Norsemans under license. This contract, although terminated soon after, was another Canadian first.

Balchen also played a significant role in the history of the most famous Canadian bush plane, the de Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beaver. Around June 1949, the United States Air Force (USAF), a new name adopted in September 1947, wanted to buy some search and rescue aircraft to support its Alaska-based squadrons. The military sales manager for the Toronto, Ontario, based aircraft manufacturer de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited (DHC) and Canada’s night fighting ace during the Second World War learned the news from a magazine article. Russell “Russ” Bannock, born Slowko Bahnuk, flew to Alaska at the controls of a Beaver. American pilots, including Balchen, were very impressed. In fact, their commander wanted to acquire a dozen Beaver.

Bannock then traveled to Washington, District of Columbia, for demonstration flights. The USAF was so impressed that it considered signing a contract for 112 aircraft. This request triggered a storm of protests. Spurred by aircraft manufacturers and the American aeronautical press, the Congress was forced to intervene. Comparative tests had to take place before the signing of a contract.

Chance smiled again at DHC in early 1950. The United States Army then wanted to buy a new light transport aircraft. Having learned the news while reading another article, Bannock performed demonstration flights. The American military men were speechless. What followed was predictable: draft contract, industry protests and comparative tests requested by the Congress. The United States Army and the USAF having decided to order the same aircraft, they organized tests that took place in January and May 1951. The Beaver prevailed over its many American opponents.

This being said (typed), the USAF tried to block the acquisition of the Canadian aircraft by the United States Army under the pretext that its weight was greater than the limit negotiated between these 2 services. Following discussions that increased this limit, DHC won the first of a series of contracts with the United States Army. The Beaver thus became the first foreign-designed aircraft ordered in peacetime by the American armed forces. Between 1951 and 1959, the USAF and the United States Army purchased approximately 980 L-20 Beaver, later redesignated U-6 Beaver. These orders were a turning point for DHC, which became dependent on its main customer, the United States Army, but back to our story.

Ellsworth and Wilkins left Chile in October 1935, aboard the Wyatt Earp, with 2 new pilots. Both British-born Herbert Hollick-Kenyon and Canadian-born James Harold “Red” Lymburner, the reserve pilot, normally flew for Canadian Airways Limited, the largest civilian operator in Canada at the time. The management of that company was understandably flattered by the fact that Wilkins believed it would have on staff the experienced pilots needed to fly over Antarctica – a risky endeavour if there was one. In any event, the Wyatt Earp arrived in Antarctica in early November. And yes, this expedition was also privately funded. By the middle of November, Hollick-Kenyon had test flown the Polar Star. Ellsworth was eager to leave for a long distance flight over Antarctica but his chief pilot chose to cancel a couple of attempts. This caution annoyed Ellsworth who considered the possibility of making the journey with Lymburner. In the end, he saw the wisdom of Hollick-Kenyon’s decisions.

Hollick-Kenyon left with Ellsworth soon after to make the long distance flight over Antarctica. Over the next 12 days, the 2 men had to land 5 times because of bad weather and, finally, lack of fuel. They covered a distance of approximately 3 550 kilometres (2 200 miles), very often over utterly unexplored territory. A Royal Research Society vessel found Ellsworth and Hollick-Kenyon in early January, slightly more than a month after their fifth and final landing.

During the flight, Ellsworth claimed a sizeable piece of Antarctica on behalf of the United States. The American government blissfully ignored this claim, as was its official policy. The United States did not lay such claims, nor did it recognise those made over the years by other countries.

Interestingly enough, the crew of the Wyatt Earp located the Polar Star. Better yet, Hollick-Kenyon seemingly flew it to the bay where the ship was moored. Returned to the United States in 1936, the Polar Star was donated to the Smithsonian Institution that same year. This historic machine is now in the collection of the National Air and Space Museum, in Washington.

In spite of their success, Ellsworth and Wilkins were not yet done with Antarctica. They left South Africa in October 1938, aboard the Wyatt Earp. Lymburner was now chief pilot. His reserve pilot and flight engineer was a Canadian by the name of Burton James Trerice. This time around, the expedition sailed with 2 aircraft, an Aeronca Model K light / private airplane and a Northop Delta commuter airliner respectively used for scouting and exploring. Faced with bad weather and extensive pack ice, the Wyatt Earp reached the shore of Antarctica only in early January 1939. Ten or so days later, Lymburner test flew the Delta. Later that same day, Lymburner and Ellsworth spent a few hours flying over Antarctica, and this is where the story gets interesting.

It so happens that, since the 19th century, some countries had laid claim to pieces of Antarctica, sizeable pieces in some cases. As we both know, Ellsworth himself had claimed a slice of Antarctica in early 1936 – a claim blissfully ignored by the American government. This being said (typed?), the State Department was now concerned by what it saw as a race to take over large swaths of Antarctica. As a result, the American consul in South Africa presented Ellsworth with secret / covert instructions before the Wyatt Earp set sail. The explorer was asked to put aside his intended itinerary, which had been made public, in order to visit another region of Antarctica that he would claim on behalf of the United States. By doing so, both Ellsworth and his homeland would be shoving aside a claim made in 1933 by the Australian government. And yes, my reading friend, you are correct. Wilkins, Ellsworth’s technical advisor and friend since 1933, was indeed Australian.

Better yet, or worse still, you choose, the secret instructions received by Ellsworth seemingly went against the widely accepted view that a land claim in Antarctica extended from the coastline all the way to the South Pole, thus creating territories similar in appearance to slices of a gigantic pie – or pizza. One has to wonder if the American government used Ellsworth to test the reaction of countries with a stake in Antarctica.

As conflicted as he might have felt, Ellsworth abided by the wishes of the American government. He claimed a piece of Antarctica on behalf of the United States during the flight of the Delta. Ellsworth quickly informed The New York Times. The article published by this daily soon made its way around the globe. Wilkins was not amused.

As this was taking place, a member of the Wyatt Earp’s crew was dealing with the consequences of a serious accident. Given the risks surrounding a surgical procedure at sea, Ellsworth set sail for the nearest port without making further land claim flights. The Wyatt Earp arrived in Australia in early February. Before long, Ellsworth seemingly stated that the region of Antarctica claimed by the United States had grown significantly since the publication of the article in The New York Times. If truth be told, said region may have been almost as large as Sweden. The Australian government immediately disputed the American claim. If truth be told, it soon bought the Wyatt Earp to further explore Antarctica and / or, if I may be permitted a personal opinion, to prevent Ellsworth from going back and making more land claims. Incidentally, Ellsworth’s 1938-39 expedition was the last privately funded foray in Antarctica.

The onset of the Second World War, in September 1939, prevented Ellsworth from returning to Antarctica, as he had hoped. Sadly enough, he was never able to go back. Ellsworth died in May 1951, at age 71.

Lymburner, on the other hand, left Canadian Airways in 1939 to work for Fairchild Aircraft Limited of Longueuil, Québec, as a test pilot. He spent much of the Second World War doing such work. Lymburner died in August 1990. He was 86 years old.

Incidentally, no less than 7 countries (Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and United Kingdom) still claimed huge swaths of Antarctica as of 2019. While no other country has recognised these claims, some have reserved the right to make claims whenever they see fit.

It occurred to me that you might be interested in a wee bit of information on the Delta. I shall be brief, of course, and please keep the moaning and eye rolling to a minimum. If you do not behave, I may pontificate on the Aeronca Model K as well. Thank you.

The Delta commuter airliner, say I, was developed in parallel with the Gamma mailplane, which was, you are quite right my reading friend, the aircraft type used by 2 of the aforementioned Ellsworth Wilkins expeditions. While the 2 aircraft shared the same wings, the fuselage of the Delta was wider and able to accommodate up to 8 passengers. An unexpected 1934 amendment to the Air Commerce Act played a cruel trick on this robust and reliable design. It stipulated that American airlines could not carry passengers in single engined aircraft at night or over areas where emergency landings could not be contemplated. Northrop thus found itself unable to sell Deltas to its main potential customers. As a result, it made only a dozen or so aircraft of this type, including 3 briefly used by American airlines. This, however, was not the end of the road for the Delta.

The first Northrop Delta delivered to the Royal Canadian Air Force, at the Canadian Vickers Limited factory, Montréal, Québec, 1936. CASM negative no 25482.

Wishing to modernise the equipment of its photographic survey units, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) chose the Delta. In early 1935, it asked Canadian Vickers Limited of Montréal, Québec, to manufacture 2 of these machines. The shipbuilder and aircraft manufacturer protested. It could cover its costs only if the RCAF increased its order to 4. The RCAF was reluctant. The parties finally came to an agreement. Canadian Vickers would produce 3 Delta right away and others later.

The first Delta, the first all-metal aircraft assembled in Canada from parts manufactured by Northrop if you must know, flew in August 1936. Canadian Vickers manufactured all the other aircraft of this type delivered to the RCAF. The aircraft manufacturer unsuccessfully tried to find civilian customers in Canada. It even prepared plans for a twin-engine version of the Delta, the Victor. These failures were not tragic, however. In fact, the total number of aircraft ordered by the RCAF increased from 3 to 7, then to 20. Following 2 incidents in 1938, the National Research Council conducted wind tunnel tests which resulted in the introduction of modified fin and rudder on Deltas produced from that date. The last aircraft of this type entered service in 1940. By the time the Second World War began, in September 1939, the RCAF was so devoid of modern combat aircraft that many Deltas conducted coastal reconnaissance missions.

It should be noted that the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, Ontario, includes the remains of a Delta. The two crew members of this aircraft, lost in September 1939, were the first casualties of the RCAF during the conflict.

Given how well you behaved, I shall refrain from pontificating on the Aeronca Model K. Farewell then, until next time.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)