Now be honest, can you tell me what a Duncan & Bayley XP-2 Skyhook is?

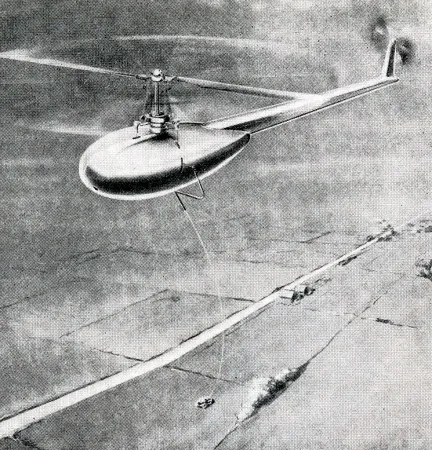

Really, do you know what a Duncan & Bayley XP-2 Skyhook is, off the top of your head, my reading friend? By the way, please accept my apologies for repeating the name of this pilotless aircraft / drone / remotely piloted vehicle / unmanned aerial vehicle. Yours truly just finds it very cool, but I digress. If truth be told, I must say I had never heard of the Skyhook before the photo above came across my path. Would you like to know more about it? No? Well, too bad, so sad.

Our story began in the United States around 1944-45, with 2 members of the small team (30 to 35 people) that put together at least 1 prototype of the Bell Model 47, a world famous type of helicopter mentioned in a July 2017 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. These men were John E. Duncan and William Hewitt Bayley.

A model airplane maker since 1929 or so, Duncan actually held several records. Seemingly during the 1930s, he was the assistant of a forgotten engineer who was trying to develop a helicopter. Sadly, Roger Sweet died before he could complete a prototype. Duncan finished this helicopter but could not find the money necessary to complete its development. He joined the staff of the Airplane Division of American aeronautical giant Curtiss-Wright Corporation in 1940. Duncan began to work for Bell Aircraft Corporation, a company mentioned in a July 2017 issue of the aforementioned blog / bulletin / thingee, in 1943. By 1947, he was the chief of model research.

Bayley, on the other hand, was a mechanic at Lockheed Aircraft Corporation who joined the staff of Bell Aircraft in 1941. By 1947, he was the assistant of the company’s commercial sales manager.

The use of models to help with the development of the Model 47 gave Duncan and Bayley an idea. They founded Duncan & Bayley Incorporated in 1945 to perfect a tiny pilotless single rotor helicopter powered by an electric motor using current supplied through a short insulated cable attached to a metal tube. This model would be the key element of a simulator used to train helicopter pilots. The 2 men completed a prototype of the helicopter in February 1947. Even though 10 or so of these machines were made, the simulator itself may not have been put in production.

As fabrication of the helicopters proceeded, Duncan and Bayley worked on a free flight version powered by a small gasoline engine. Offered as a kit to modellers, this new machine would be the very first helicopter model on the market. It looks as if this innovative design was not put in production either.

In spite of it all, Duncan and Bayley remained fascinated by the progress made in the development of practical helicopters. It occurred to them that a small pilotless flying machine of that type could fulfil a variety of civilian and military missions, from low level weather data gathering and photo survey work to radio antenna testing, and this at a very low cost.

The drone Duncan & Bayley developed, one of the first if not the first of its kind in the world, was a small single rotor helicopter powered by an electric motor using current supplied through a 150 metre (500 feet) insulated cable attached its carrying case. Yours truly does not know if the aforementioned carrying case could be plugged into a power source or included a battery, or both. In any event, the whole kit and caboodle weighed about 23 kilograms (50 pounds). Designed to carry a camera or some other type of sensor, the easily disassembled Skyhook tipped the scale at less than 7 kilograms (not quite 15.5 pounds).

Several prototypes of the Skyhook (10 or so?) were airborne by the summer of 1948. They reached altitudes of at least 60 metres (200 feet). The production version of the drone would be able to fly unattended for extended periods of time at any desired altitude, up to 150 metres (500 feet) of course, despite winds of almost 50 kilometres/hour (30 miles/hour). Unlike the prototypes, this version would not have a 4-legged landing gear. It would alight in some sort of cup. Confident that their drone had a bright future, Duncan & Bayley concluded a production agreement with a small tool manufacturer, General Riveters, Incorporated. Sadly enough, the company’s hopes were unfulfilled. No one knocked on its door. It considered the possibility of using the control system of the Skyhook to develop an autopilot for piloted helicopters. A prototype of this device may or may not have been built. In any event, Duncan & Bayley seemingly went out of business in the late 1940s or early 1950s.

Would you believe that a drone similar in concept to the Skyhook was developed in Canada in the 1960s? If you’re as good as gold, yours truly might offer you a text on this fascinating concept. In a few years, of course.

Is that it, you ask? Well, no. Of course. It so happens that Bayley was seemingly married to one Isabel Bayley, born Isabel Levin. Around 1946-47, this American Second World War veteran, who had served in the Women’s Army Corps, compiled the journals of Arthur Middleton Young. This inventor, helicopter pioneer and engineer at Bell Aircraft was heavily involved in the design of the Model 47. Young, who was also a philosopher, cosmologist and astrologer, later revised the text prepared by Bayley and published it under his name, in 1979. The Bell Notes: A Journey from Physics to Metaphysics contained a lot of information on the origins of the Model 47. The later chapters of the book, on the other hand, were quite esoteric, to say the least.

Isabel Bayley went on to edit a book containing the best of the thousands of notes written by a famous American novelist and short story writer. Letters of Katherine Anne Porter was published in 1990. She died in Scarborough, Ontario, in 1993. Her husband, or ex-husband, passed away in the United States in 2002.

Is that finally it for today? Of course not. On a serious note, yours truly has to admit that one of the things that attracted me to this story, besides its quirkiness and innovative nature, was the very designation of the Skyhook. You see, my father was a textile worker who spent a great many years in a noisy and dusty mill operated in Sherbrooke, Québec, by Dominion Textile Incorporated, one of the big players in the Canadian textile industry for a good part of the 20th century. The automatic looms he repaired during many years were XP-2s, a type seemingly designed and manufactured by Draper Corporation. This company was one of the most important manufacturers of power looms in the United States during the first half of the 20th century.

From the looks of it, the XP-2 was a descendant of the Northop automatic loom initially offered for sale in 1894. Its inventor was James Henry Northrop, a gentleman who should not be confused with Marvin A. Northrop, the owner of a small American company, Marvin A. Northrop Airplane Company, that supplied aircraft parts to homebuilders, rebuilders and repair stations, as well as plans for a primary glider known as the Northrop glider. A few examples of this simple single seat machine were made in Canada during the 1930s.

One of these was built by the Ottawa Glider Club, in Ottawa, Ontario. Interestingly, the first 25 members of this group worked for Ottawa Car Manufacturing Company or an associated company, Armstrong Siddeley Motors Limited, a subsidiary of Armstrong Siddeley Development Company, a British firm. Thanks to the kind cooperation of the Ottawa Flying Club, said group went to Uplands airfield, known in 2018 as Macdonald-Cartier International Airport, to try out its machine, in May 1930. Despite several mishaps and minor crashes, the glider flew for some time. A subsidiary of Ottawa Electric Railway Company, itself a subsidiary of Ahearn & Soper Limited, Ottawa Car Manufacturing was a maker of streetcars and buses interested in aviation. And no, my over enthusiastic reading friend, Armstrong Siddeley Development was not mentioned in a May 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. A British company by the name of Armstrong Siddeley Motor Limited was the firm mentioned in that article.

The inventor of the Northrop automatic loom was equally unrelated to one of the great aeronautical engineers of the 20th century, the American John Knudsen “Jack” Northrop. And yes, contained within the exceptional collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa are the battered remains of a Northrop Delta photo mapping and coastal patrol aircraft. The crew of the museum’s machine, lost in September 1939, were the first Canadian servicemen to die during the Second World War.

And yes again, this collection also includes a Canadair CF-116 supersonic fighter bomber, an improved version of the Northrop F-5 Freedom Fighter made under licence by Canadair Limited of Cartierville, Québec.

A rather interesting production project concerning this family of aircraft came forth in 1988. Bristol Aerospace Limited of Winnipeg, Manitoba, was considering the possibility of re-launching the production of the Northrop F-5 Tiger II supersonic fighter-bomber, an upgraded version of the Freedom Fighter. Indeed, this subsidiary of British giant Rolls-Royce Limited was also thinking of launching the production of a derivative of the Tiger II, the F-20 Tigershark, a much more versatile and efficient single engine aircraft. However, this private project of Northrop Corporation did not find a buyer among the air forces of secondary importance for which it is designed. They preferred to order an aircraft used by the United States Air Force, the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon. The death of 2 test pilots when prototypes crashed was also detrimental to the Tigershark’s reputation. After 6 years of trying to get orders, Northrop abandoned the aircraft in December 1986.

Bristol Aerospace’s both projects were the result of a recent refurbishment contract for approximately 50 CF-116 of the Canadian Armed Forces. To its great surprise, the company was contacted by the air forces of some foreign countries who wish to purchase up to 250 refurbished or newly manufactured aircraft. The Brazilian Air Force, or Força Aérea Brasileira, for example, wished to acquire 50. Despite the efforts of Bristol Aerospace, the Tiger II and / or Tigershark production projects did not proceed beyond the discussion stage.

Would you believe that, in 1967, Draper was taken over by Rockwell-Standard Corporation? By then, the company’s looms had to contend with more advanced machines from overseas, especially Japan. Dominion Textile, for example, chose to replace its XP-2s with looms made by Sulzer Aktiengesellschaft. My father and a few other machinists spent several weeks at the company’s facility, in Switzerland, in the mid 1970s I believe, to learn how to operate and repair the new machines. Upon their return, they trained other machinists.

Interestingly or not, you choose, Rockwell-Standard took over North American Aviation Incorporated, one of the great aircraft makers of the 20th century, in 1967, to form North American Rockwell Corporation. In the early 1970s, de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited, a well known aircraft maker if there was one, signed an agreement with this firm to promote a more powerful version of its DHC-5 Buffalo short take off and landing military transport plane. The project went nowhere. And yes, my attentive reading friend, the Buffalo was mentioned in a March 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. You will remember, I hope, that this writer remains very interested in adding one of these remarkable machines to the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum.

Rockwell International Corporation, a new name adopted around 1973, would go on to make 5 spaceworthy Orbiter Vehicles, or Space Shuttles, for the Space Transportation System of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. And yes again, the Canada Aviation and Space Museum has on display the very first Shuttle Remote Manipulator System, a huge robotic arm better known as the Canadarm. This technological jewel was loaned to the museum by the Canadian Space Agency. The museum also has on display a Space Shuttle tire loaned by that same agency. And yes, the Orbiter Vehicle was mentioned in a July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Now that’s it for today, and… All right, all right. We do have time for another digression, if you insist. In 1892, an individual and a small company in England completed a piloted ornithopter for Ross Franklin Moore, a retired major who had served in India with the Royal Engineers of the British Army. Similar to the Skyhook in concept if not in appearance or size, this tethered flapping wing machine was fitted with an electric motor linked by cables to a pair of high voltage power lines. Designed for use as a survey or observation platform, it proved unable to fly. This ornithopter was one of the more then 30, yes 30, motorised or human-powered heavier than air flying machines put together at least in part before the December 1903 flights of Wilbur and Orville Wright. Interestingly, Moore immigrated to Canada around 1910. He died in Victoria, British Columbia, in 1923, at the age of 76.

Live long and prosper, my reading friend.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)