A dog, a mouse and a Sputnik

Hello, my reading friend, hello. Would you be unhappy if yours truly brought to our menu a largely spatial subject? Yes? No? Oh I see. Very well. We will talk about space today, despite all opposition. Indeed, the august institution for which I have the honour and pleasure of working, most of the time, is the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, Ontario. You will notice the presence of the word space in this name. I would therefore like to highlight this week the 60th anniversary of the premiere of a French feature film. The picture used to launch this venture came from a weekly newspaper, Photo-Journal, published in the metropolis of Canada, Montréal, Québec. More specifically, it came from the number covering the period from 23 to 30 August 1958.

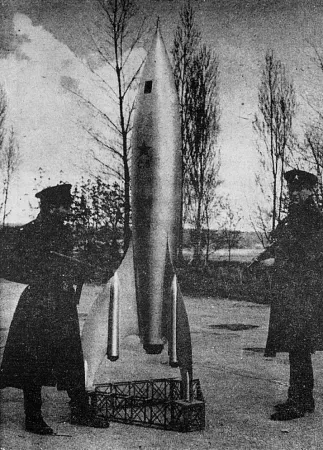

Allow me to quote the short text that accompanied our photo.

Conquering the Moon ...

In the fierce international competition for the conquest of space, France does not intend to stay behind Russia and the United States. General de Gaulle would like to bring his country into the club of atomic powers but as the Americans share their secrets only with the English, and as it is useless to speak to the Russians, it turns out that the first French rocket was prepared ... in a movie studio!

After feverish research, the “scientists” have developed a rocket capable of launching a satellite in the infinity of space; it will be seen in the film “A pied, à cheval et en Spoutnik,” which is currently being filmed in France with the famous comedian Noël-Noël. The machine is ready, and while we wait for its launch at any time, a flock of sheep grazes the grass all around it. Obviously, sheep brains do not understand the greatness of the “French mission in the world” ...

Given that the style and tone of this text did not particularly correspond to those of the articles published in Photo-Journal, yours truly wonders if this long quote did not actually come from a French news agency. Now that this quote and its commentary are behind us, let us get to the heart of the matter.

Our story began in September 1957 when a new feature film hit screens in the city of Paris. À pied, à cheval et en voiture was one of the most popular French comedies of its time. And yes, you read well, my reading friend, this film was not the one whose name appeared in the caption of the photo that accompanies this article. And no, this film had nothing to do with the first artificial satellite, Sputnik I, launched by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in October 1957 – a satellite mentioned in a July issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

The plot of À pied, à cheval et en voiture can be summed up in 4 and a half lines, 65 words and 395 characters, spaces included. Its main character, a hero or antihero, the choice is yours, was named Léon Martin, played by Noël-Noël, born Lucien Noël. This accountant in a funeral home bought a car, a second-hand car actually, make himself look better to the wealthy and aristocratic father of the young man that his daughter adored. This acquisition soon provoked a series of somewhat unexpected and very amusing mishaps.

The success of À pied, à cheval et en voiture resulted in the production of another feature film, entitled, you guessed it, À pied, à cheval et en Spoutnik. Apart from its title and several characters and actresses / actors, this film, which arrived in cinemas in September 1958, a few days after the publication of the article of Photo-Journal, had nothing to do with its predecessor. This being said (typed?), its plot turned once again around Martin. Our hero / antihero was now amnesic, following a car accident. A great calm being recommended to him, his wife, Marguerite, took him to the country. Martin spent his days in peace, gardening, without a radio, nor newspapers. What is it you are saying, my reading friend? No, Martin did not have Internet access. Let’s be serious please. The year was 1958. There was not even a television set in the house where he lived.

One day, Martin found a dog and a mouse near his house. He thought he recognized Friquet, his dog, who had been missing for some time, and took it with him. Although delighted, Martin did not understand why his good friend refused to eat. You will understand, my brilliant reading friend, that this was a case of mistaken identity. The dog’s name was actually Fédor. It and the mouse were on board a Soviet satellite that had accidentally landed in France. In fact, Martin’s wife, who was in Paris to help her daughter, who was about to give birth, saw a report to that effect on television. The dog, it was said, only ate after hearing a ring.

Meanwhile, Martin was surprised to see the mouse show up at his home. The dog seemed to recognize it and did not attack it. Let’s not forget that the word “sputnik” meant fellow traveler. At the sound of a ring, the dog and the mouse ate with enthusiasm. Confused as always, Martin concluded that Friquet / Fédor had been kidnapped and trained by one or more unidentified individuals. Before I forget, allow me to point out that Martin christened the mouse Marguerite, much to the chagrin of his wife.

And yes, my reading friend and comrade, the phrase fellow traveler could have a pejorative meaning. At the time that concerns us, 1958 that is, right smack in the Cold War, a fellow traveler was a person who sympathized with communism without being a member of a communist party. Such people often seemed suspicious to the governments of the member countries of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, of which Canada was a part, but I digress.

As you can easily imagine, the Soviet government told its French counterpart that it wanted to recover its dog, mouse and satellite. It offered an important reward to anyone who found Fédor. The mayor of the municipality where Martin lived visited him to ask that he return the 2 animals to representatives of the Soviet government. His action failed. A French diplomat had no more success. Martin, who was gradually regaining his intellectual faculties, had no intention of allowing himself to be pushed around. He appreciated more and more the company of the Soviet canine. Barricaded in a barn, Martin resisted the zany efforts of local police and firefighters trying to dislodge him.

A Soviet diplomat finally went to Martin’s home. He offered him to bring the dog and mouse back to Moscow. Our hero accepted. He and his wife flew soon after to the USSR. Their aircraft landed at Vnukovo international airport, not far from Moscow, a site mentioned in an April 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

It was with great sadness that Martin handed over Fédor to the researchers who wished to examine and prepare it, very secretly, for another flight in space. While this work continued, the Soviet government invited Martin and his wife to large receptions where they met the highest authorities of the USSR. Better yet, the Martins were invited to the launch of the rocket that was to carry Fédor and a Soviet researcher, Professor Popov, the first human in space, on a trip to the far side of the Moon. This news greatly affected Marin who feared for the life of his friend.

To everyone’s surprise, the rocket refused to work. Overwhelmed by emotion, our hero went to the cabin of the rocket to say goodbye to his canine friend. Before Martin had time to get out, one of the Soviet researchers who were arguing hard to find out what was wrong accidentally launched the rocket. The journey into space was without accident. At some point, however, the device that created / maintained an artificial gravity in the cabin was disabled. Martin, Popov, Fédor and the mouse floated in the cabin. Martin, completely lost, hit the ceiling and floor. Popov re-engaged the mechanism as soon as he could.

To kill time during the trip to the Moon, Popov read a Jules Gabriel Verne classic written in 1869, 20,000 lieues sous les mers, a somewhat unusual choice for a trip to the Moon. And yes, my reading friend, 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, the English version of this novel, was mentioned in a July issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

The Soviet researcher having fallen ill, Martin had to take control of the rocket. Soviet researchers guided him in his efforts. After flying over the Moon, the Frenchman managed to land the rocket in the USSR. He was obviously given a hero’s welcome. Martin and his wife soon returned to France, accompanied by Fédor. The three of them lived happily ever after, provided that the family car ran, of course. Said car was a Renault 4 CV, a very interesting vehicle that will not be discussed today. No, no, do not insist, my eager to knowledge reading friend. You do not have the financial means to bribe me, for the moment. You will have to wait to savour the joy of reading a text on the 4 CV.

Yours truly would like to be able to say that À pied, à cheval et en Spoutnik was as successful as À pied, à cheval et en voiture. Unfortunately, this was not the case, and this despite an excellent cast of comedians. This being said (typed?), this feature film did not lack humour. This very French humour was obviously well anchored in its time. In other words, it might not be to the liking of a North American viewer of the year 2018. By the way, if the American title of the film, A dog, a mouse and a Sputnik, could not be more reasonable, one certainly could not say as much of the one imagined by the British. Hold tight for the satellite did not mean a thing. Even worse, this title was grammatically incorrect.

Much of the appeal of À pied, à cheval et en Spoutnik resulted from the fact that this film was one of the rare satires of the space race of the 1950s and 1960s. The director gently mocked French and Soviet diplomats, politicians and researchers for example. This being said (typed?), the scenes taking place in the USSR may have vacillated a bit too much between a clear desire to make people laugh / smile and an apparent desire to seriously present the USSR’s achievements in rocket science. In fact, the Soviet characters were treated with humanity. As awkward or ridiculous as they may have been, these women and men were not bloodthirsty monsters. If you think about it, satirical science fiction movies are not all that numerous. The rare examples that come to the mind of yours truly made fun in most cases of feature films that took themselves very (too?) seriously.

It goes without saying that À pied, à cheval et en Spoutnik was inspired by the launch of the Soviet artificial satellites Sputnik I and, even more, Sputnik II, launched in October and November 1957. You will remember, I hope, that this second satellite was mentioned in a July issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. However, I wish to mention, memory being the faculty that forgets, that Sputnik II carried the female dog known worldwide as Laïka – the first cosmonaut / astronaut if I may say so. This poor animal without history or pedigree died a few hours after the launch of the satellite. The French screenwriter and director’s goal being to make people laugh and smile, they chose to keep Fédor fully alive.

They also imagined, and correctly so, that a Soviet rocket would place the first human being in orbit. Of course, you know the name of this person, my reading friend. Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin, you say? Right answer! This fighter pilot, also mentioned in a July issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee, became the first cosmonaut / astronaut in history in April 1961, but let’s get back to our story.

The conditioning of the Soviet dog and mouse was a clear nod to the work of Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. During the 1890s, while researching digestion, this Russian physician and physiologist noted that the dogs he used produced saliva even before touching their meal. Pavlov managed to make these animals salivate by using various visual and sound stimuli (whistle, metronome, tuning fork, etc.) which informed them that their meal was coming. He thus discovered the principles of conditional, and not conditioned, reflex – a misinterpretation linked to a bad translation of his works. In 1904, Pavlov won the Nobel Prize in Medicine / Physiology. He was the first Russian researcher to win one of these internationally recognized awards.

Let’s mention in passing that the rocket designed by the crew of À pied, à cheval et en Spoutnik was very similar to the one seen in Destination Moon. Released in June 1950, this American film was one of the first, if not the first serious feature film in colour dedicated to the exploration of space. I must confess to thinking about writing a text on this most interesting film.

The rocket in À pied, à cheval et en Spoutnik was also very similar to the one imagined by an extremely well known Belgian cartoonist, Hergé, born Georges Prosper Remi, in his album Explorers on the Moon, a classic graphic novel released in French in 1954 and mentioned in a July issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. In fact, dare I suggest that there is a certain parallel between Martin’s spatial misadventures and those of the inimitable Thomson and Thompson, those representatives of law and order who sowed disorder wherever they went?

And yes, my reading friend, you are right. The researcher behind the space programme in Explorers on the Moon was none other than Cuthbert Calculus, a world-renowned figure also mentioned in the aforementioned July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. And no, Thomson and Thompson were apparently not twins. Many tintinophiles believed that they were look-alikes, or cousins, and ... These successive reminders to one or more July 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee seem to annoy you, my reading friend. If so, yours truly apologizes for it. I pinkie swear that I will not include other reminders in this article.

A cinephile with eyes wide open will note that the rocket returning to Earth at the end of À pied, à cheval et en Spoutnik is not the one lifting off earlier in the story. The director was using footage of an American Convair SM-65 Atlas, an intercontinental ballistic missile with a (thermo)nuclear warhead mentioned in a July issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Oops, I forgot that reminder. Sorry. If such a borrowing seemed a little unfortunate to a person living in 2018, the fact was / is that many filmmakers have used this approach over the decades.

This being said (typed?), the team behind the special effects of À pied, à cheval et en Spoutnik had no reason to be ashamed of its work. Its achievements compared very well with those of other teams of the time. They were even slightly better than what was done in Europe at the time. Just think of the scenes taking place in Moscow, which used excerpts of film showing the Soviet capital. Yours truly, however, must recognize that the presence of a device that created / maintained an artificial gravity in the rocket cabin had no scientific basis.

The wing nut who resides in me could not resist the temptation to mention an aircraft visible for a few seconds around the middle of À pied, à cheval et en Spoutnik. The 4-engined airliner that brought Martin and his wife to Vnukovo international airport was a Douglas DC-7 from the Compagnie de transports aériens intercontinentaux (TAI), a French private airline mentioned in a March 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Re-oops, really sorry. The presence of this DC-7 in the USSR may have made some cinephiles smile. Indeed, TAI served primarily French colonial territories in Africa, Asia and Oceania.

By the way, this DC-7 ended his career with the Armée de l’Air. The French air force used this aircraft, known as the Avion de mesure et d’observation au réceptacle (AMOR), to gather data during tests of intermediate-range missiles fitted with a (thermo)nuclear warhead. This unique DC-7 was scrapped in the mid-1970s, which was a shame. And yes, my exasperated reading friend, these warheads may have been tested on the Antarès experimental rocket of the Office national d’études et de recherches aérospatiales (ONERA), mentioned in a July 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Apologies for this reminder, but as the friendly but somewhat deranged pirate Jack Sparrow, sorry, captain Jack Sparrow, said so well, I couldn’t resist.

See you.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)

![Peter Müller at the controls [sic] of the Pedroplan, Berlin, Germany, March 1931. Anon., “Cologne contre Marseille – Le mystère du ‘Pédroplan.’ [sic]” Les Ailes, 2 April 1931, 14.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-04/Les%20Ailes%202%20avril%201931%20version%20big.jpg?h=eafd0ed4&itok=WnBZ5gMf)

![One of the first de Havilland Canada Chipmunk imported to the United Kingdom. Anon., “De Havilland [Canada] DHC-1 ‘Chipmunk.’” Aviation Magazine, 1 January 1951, cover.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2021-01/Aviation%20magazine%201er%20janvier%201951%20version%202.jpg?h=2f876e0f&itok=DM4JHe5C)