Archives numériques : Les enfants invités au Canada

À l’occasion de la Semaine de sensibilisation aux archives (du 2 au 8 août), Ingenium met en valeur quelques joyaux de sa collection numérique. Ce texte a été adapté à partir du site Web Histoires en images, développé par le Musée des sciences et de la technologie du Canada en 2006.

Dès 1933, avec l’arrivée au pouvoir d’Hitler, le gouvernement britannique a commencé à se préparer pour la guerre contre l’Allemagne. De nombreux Britanniques étaient inquiets, non seulement du bombardement des villes, mais de la menace d’une invasion et d’une occupation militaires de l’armée allemande. La peur d’une invasion faisait croître les préoccupations pour la sécurité et la liberté des enfants britanniques. À partir de 1935, un plan d’évacuation des enfants des grandes villes, comme Londres et Liverpool, pour les envoyer vers les campagnes a été mis en œuvre par des représentants du gouvernement. Lorsque la Grande-Bretagne a officiellement déclaré la guerre à l’Allemagne, en 1939, après la chute de la majeure partie de l’Europe continentale, le danger d’invasion semblait imminent.

Le premier ministre britannique, Neville Chamberlain, a déclaré la guerre à l’Allemagne le 3 septembre 1939. Au cours des premiers jours de septembre, près de 3 000 000 d’enfants britanniques étaient déplacés des grandes villes vers les régions plus rurales du pays. Toutefois, après avoir vu sur des photos et des films sur les horreurs de l’invasion de la Pologne et de la France, de nombreux parents ont décidé d’envoyer leurs enfants dans des pays plus éloignés des zones de guerre.

Au début, les évacuations étaient privées. Les gens s’organisaient avec des parents ou des amis au Canada, en Afrique du Sud, en Nouvelle-Zélande et aux États-Unis. Dans certains cas, des écoles entières étaient transférées dans des endroits pouvant les accueillir. Les entreprises britanniques qui avaient des succursales au Canada ont également mis sur pied des programmes d’échange, comme l’ont fait les universités et les églises.

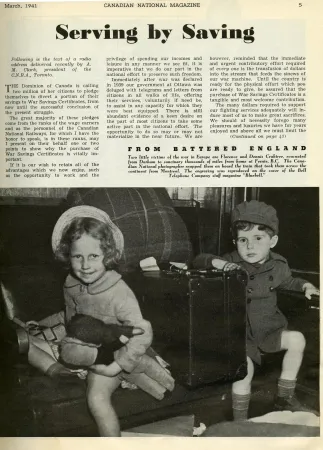

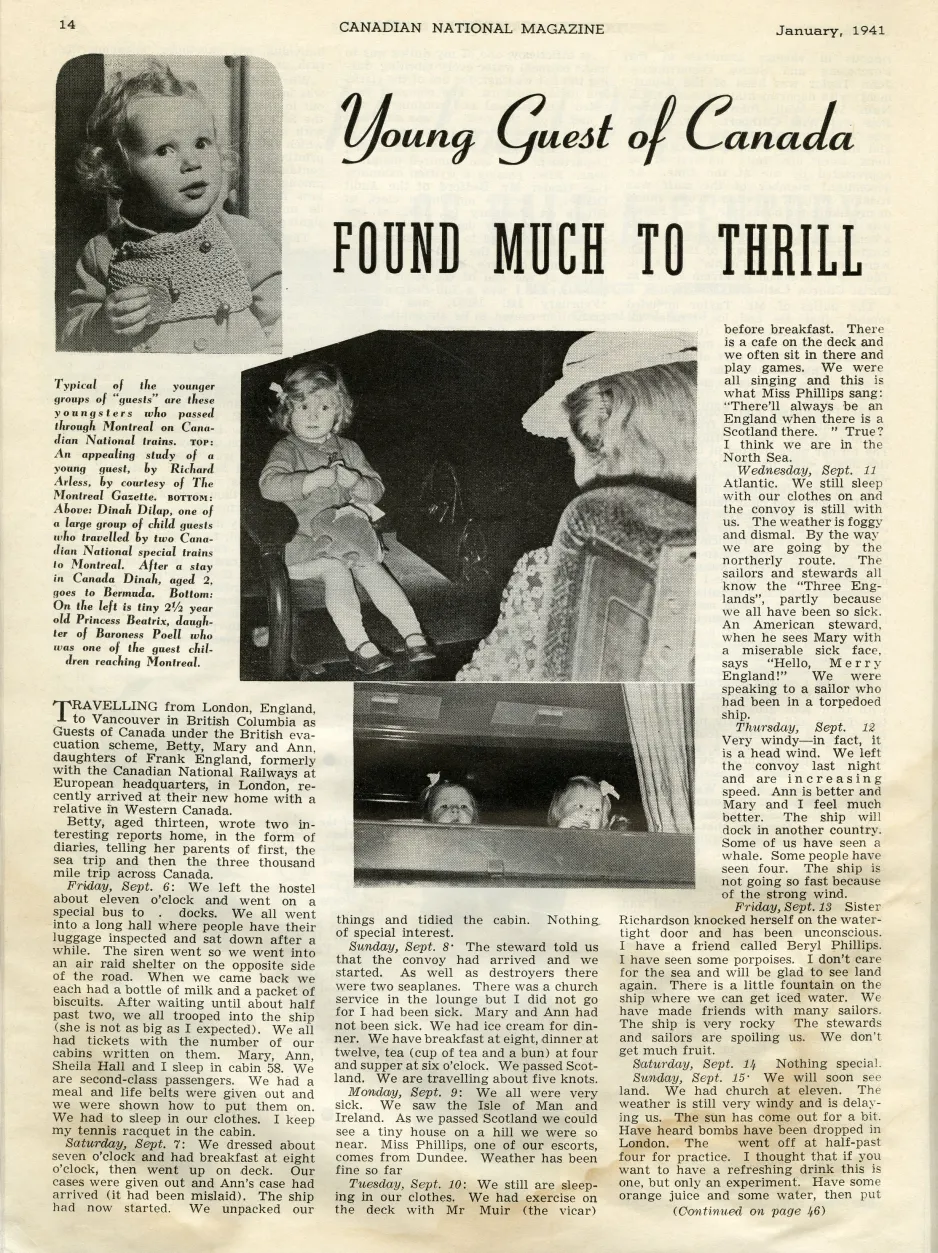

Article from Canadian National Magazine, January 1941, entitled "Young Guest of Canada Found Much to Thrill". Featured photos of guest children on CN trains, as well as a travel diary written by 13-year-old Betty England during her voyage.

As the bombings increased in frequency and intensity, it became clear that Germany was not merely targeting military structures, but deliberately bombing civilian targets in an attempt to terrorize the British people. Some members of the British government quickly began organizing a system to get children out of the country. The Children’s Overseas Reception Board (CORB), was immediately swamped with more than 200,000 applications.

CORB tried to eliminate the element of class from the selection process by paying for all travel costs and living expenses of evacuated children. The response by volunteer families in host countries was overwhelming, and there was no shortage of homes for the children. However, screening host families so that the abuse that had occurred with the Home Children immigration program presented a problem, even as organizations sprang up in host countries inspect applicants. Many parents also worried that they would never see their children again. Some never did. Most of the children who left Britain in the summer of 1940 did not return to their families until the end of the war, between 1943 and 1945.

Canadian destroyers in line astern, steam out to sea to take up their positions in convoy, ca. 1942.

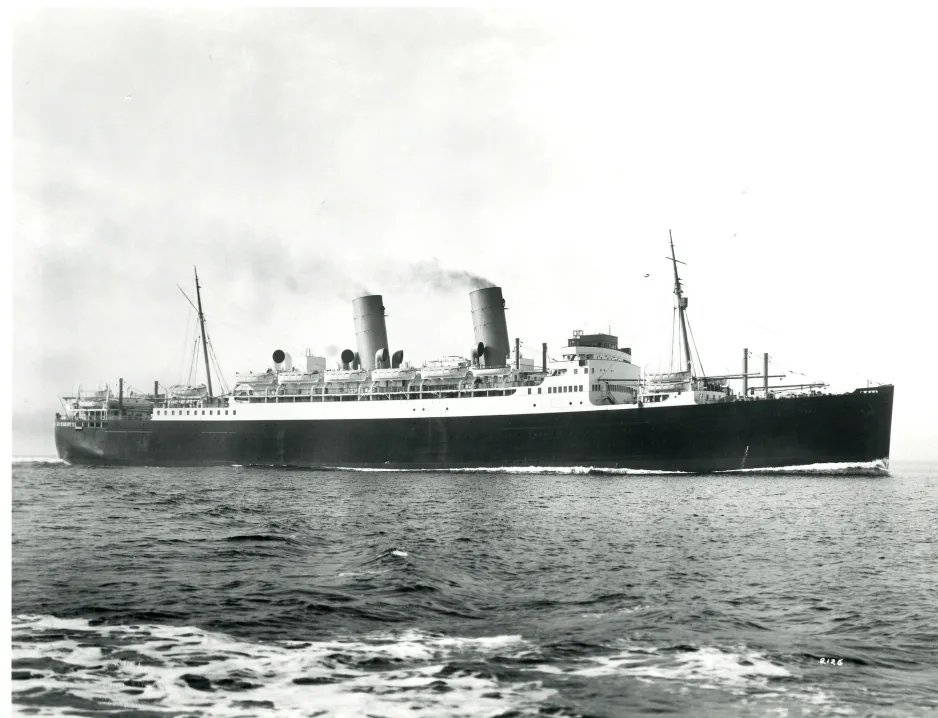

The first ships carrying CORB children left Britain in June 1940, and continued over the course of the summer. The government insisted that ships travel as part of a convoy, which left on an irregular schedule from Liverpool and Greenock, near Glasgow. The convoys were under constant threat of attack from airplanes, surface vessels and, most frighteningly, submarines (U-Boats).

Tragedy struck in September 1940, when the City of Benares, a ship carrying 90 CORB children, was sunk by a German U-boat. Rescue efforts were hindered by rough seas, and only 13 children were saved; they were found half frozen and clinging to lifeboats in the North Atlantic. The CORB program was shut down soon after. By then, the tide of the war was changing, and it appeared that Britain was going to withstand the German attack. The need to evacuate lessened and the number of evacuees dwindled, coming to a complete halt by the summer of 1941.

Many of the children arrived on re-purposed cruise ships, such as Canadian Pacific’s Duchess of York, pictured here.

In its short existence, CORB evacuated 2664 children, 1532 to Canada. It is believed that another 6,000 children to Canada through private arrangements. For the children, this was a life-changing event. After five years in a new home with a new family in a new country, many had spent the majority of their lives in another culture. Many found it difficult to adjust to life back home in Britain, which was under rationing for some years after the war ended.

This photograph shows child evacuees from the U.K. arriving at Montreal's train station in the summer of 1941.

Many children were evacuated as young teens and, five years later, had difficulty leaving behind their new lives. Some children, having left their parents when they were barely toddlers, had no memory of the distant land called Britain, or of their parents. Many Guest Children eventually returned as immigrants to their host countries. Many also remained in close contact with their overseas families over the course of their lives.

The Canadian National Railway photo collection at Ingenium documents Canadian life during the Second World War. Visit our new Digital Archives portal for more photographs.