Women in aviation: A conversation with Brigadier-General Lise Bourgon

This fall, the Canada Aviation and Space Museum proudly welcomed a helicopter from the Royal Canadian Armed Forces (RCAF) into the museum's permanent collection. Operational for more than 50 years, the Sikorsky CH-124B Sea King is a twin-engined, anti-submarine helicopter that has earned a trusted reputation amongst Canadian military aircraft of the twentieth century.

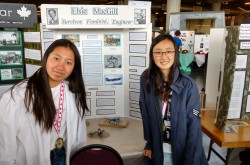

Brigadier-General Lise Bourgon has flown the very Sea King that will soon be proudly displayed at the museum. A woman of many “firsts,” Bourgon was the first female pilot to command a squadron, as well as the first to be promoted to lieutenant, lieutenant colonel, and general. She was the first female wing commander at 12 Wing Shearwater. When she led the Joint Task Force in Iraq, Bourgon became the first female to command a Canadian combat mission overseas.

The Ingenium Channel caught up with Bourgon to talk about her decorated career, her extensive experience with the Sea King, and what it takes to be a woman who pushes the boundaries of success.

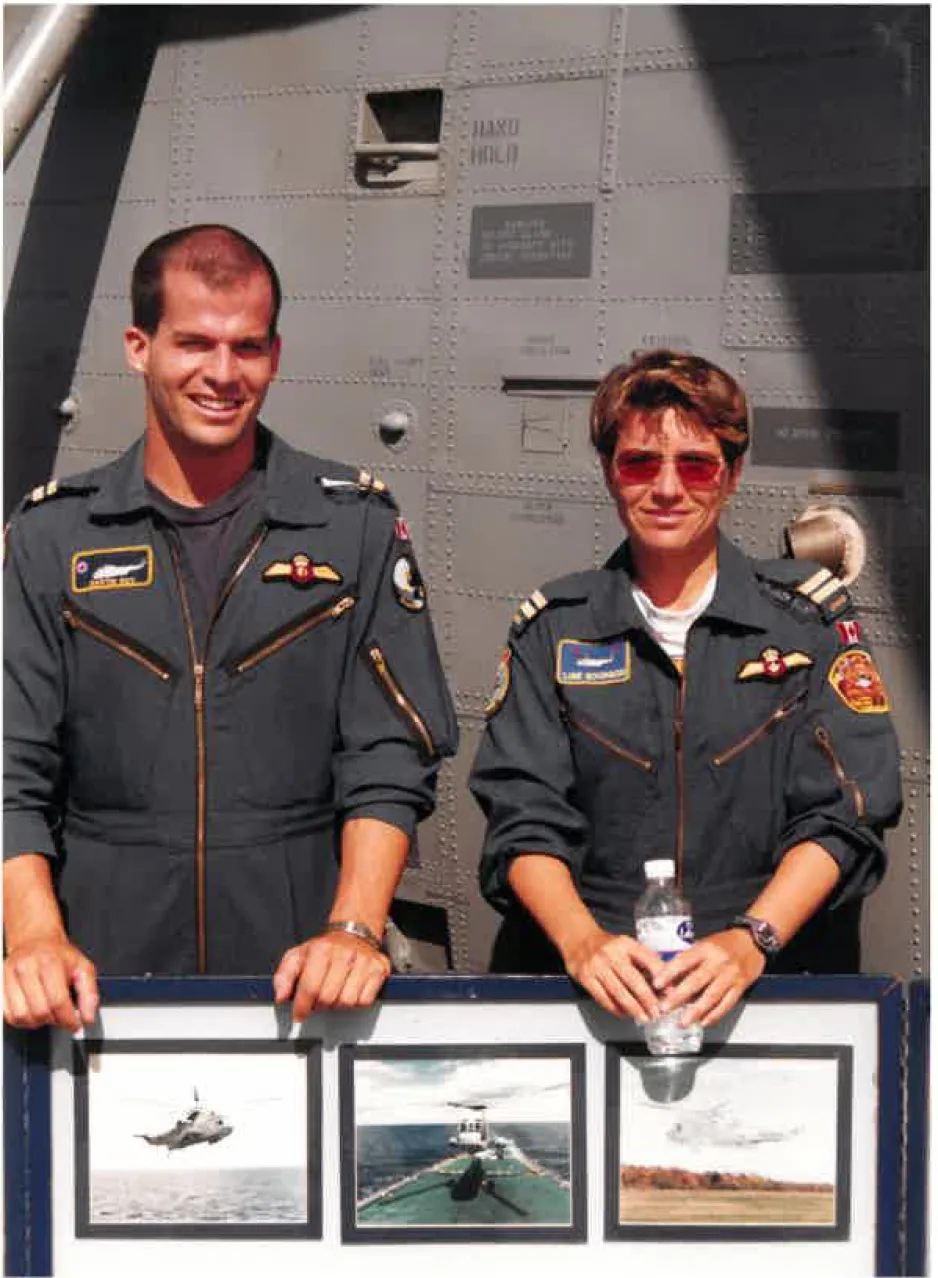

Captain Bourgon poses in front of the Sea King in Shearwater, Halifax in 1995.

Ingenium Channel (IC): You’ve been quoted saying that you first joined the RCAF for the free education, and didn’t intend to stay. What made you change your mind?

Brigadier-General Lise Bourgon (LB): I came in for the free degree and I just happened to be selected in one of the first windows of female pilots — when they opened the trade to females, so I gave it a try. Through my pilot training, I always wanted to be a tactical pilot, I wanted to fly the Twin Huey — that was my dream. When I got my wings and I was selected for the Sea King, I was not a happy camper because that’s not what I wanted at all. However, my first deployment at sea — landing the Sea King on the back of a ship — that’s when I fell in love. That was the turning point for me for my career, was going to sea. I love going to sea, and I love the Sea King — so the two of them together really changed everything for me. Every new job was an awesome opportunity and I never stopped having fun.

IC: As you know, the Canada Aviation and Space Museum is adding a Sikorsky CH-124B Sea King to its collection. Tell me what this helicopter means to you.

For me, the Sea King is the workhorse of the RCAF. It’s a helicopter that could do — and did — everything. One day we were doing anti-submarine warfare, the next day we were doing search and rescue, the day after we were going to get parts. Offshore we were doing medical evacuation, surface surveillance; there were so many things we could do — it was great.

~ Brigadier-General Lise Bourgon

LB: It also gave me the opportunity to travel the world; you went where the ship went. One day you were in the Mediterranean, the week after you were in the Persian Gulf. My first year in the squadron as an operational pilot, I sailed for nine out of 12 months. I think in that nine months, I saw 17 different countries and 24 different ports. We went everywhere; we travelled the world and we had our own helicopter landing pad all over the place. That was exciting.

Captain Bourgon and her husband, Martin Roy, stand next to the Sea King at the War Museum in 1998.

IC : What sort of training goes in to learning how to fly a Sea King?

LB: All of our helicopter pilots used to be trained on the Jet Ranger in Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, and once you have your wings you’re assigned to an operational task: search and rescue, supporting the Army, or supporting the Navy with the Sea King or the Cyclone.

Once you’re assigned, you go to the operational training unit. For the Sea King or the Cyclone it’s the 406 Training Squadron in Shearwater, Nova Scotia. At the time, it was about six months where you learn to fly the machine and fight with the machine. Now you also have to fulfill your military role — which is often to fight — with your platform. After six months, you graduate as a co-pilot, meaning you fly with someone who has more experience than you. Throughout, as you’re flying as a co-pilot with your aircraft captain, you do all kinds of training and more studying, so you get better and better. It takes about two years to upgrade to be the aircraft captain; so now you’re the senior pilot and you’re the one responsible to train a new co-pilot.

There’s also a third category in the Sea King which is the crew commander. He or she is responsible for fighting, for the tactics being used for the actual mission that you’re conducting — if you’re chasing a submarine, using anti-torpedos, using machine guns, search and rescue. That’s usually another year of training and simulators to reach the category of crew commander. From the time you graduate from operational training to becoming crew commander, it takes about three years of continued studying, practise, drills, exercise, and exams. That’s the thing with the military — you never stop learning. When you think you’ve reached the top of your game, they throw something else at you and you go back to school.

A light-hearted moment at Colonel Bourgon’s outgoing change of command ceremony, as she takes a ride with her daughter, Megan Roy.

IC: You’re an extremely accomplished and well-respected female in the RCAF. What have been your biggest challenges in getting to where you are today?

LB: I always go back to work-life balance, and trying not to sacrifice the family as you’re doing your job. It’s a very thin line of trying to do the best you can — the best mother, the best spouse — but also being the best officer in the RCAF and the best pilot. But nobody can be the best at everything, so I think it’s about compromise and accepting that you’re not the best at everything, and being happy in the balance that you can achieve.

I’ve been super lucky that my husband is a great man. They say, “Behind every great man is a great woman,” well, I have to say that behind every woman is probably an even greater man. My husband, Martin, supported me while I had to deploy, and he always allowed me to be promoted and pursue opportunities. It’s truly a team effort; I would not be where I am if I didn’t have the great husband that I have.

I don’t think our society has changed as much as it needs to for that balance; it’s kind of expected for women to stay behind and support the man, but the reversal where a man sacrifices a bit of his career to support his wife and family — sometimes my husband would get looks and questions. But what’s the difference? They are as much his kids and they are my kids, but not everyone has that attitude.

We’ve moved the kids (Jeremy, 19 and Megan, 17) all over the place, but I think they’re so well adjusted and mature. I guess the future will tell — either they’ll never move because we’ve changed their roots so many times, or they’ll always be looking for change.

Colonel Bourgon salutes during her outgoing change of command ceremony for 12 Wing Shearwater in April 2015.

IC: What else needs to happen within the RCAF in order for gender integration to see continued success?

LB: I don’t see gender integration as a number, but as a state where the opportunities are the same between men and women. Honestly, I think we’re there; in the RCAF it doesn’t matter if you’re a woman or a man — you are given the same opportunities for success, for courses, for deployment. Now, it’s just trying to convince society to join the military. We’re still fighting societal and cultural beliefs — women don’t see themselves joining the military because they don’t think they can do it. Until we can change that societal belief — so women look at the military as a place where they belong — that’s going to be the key.

I imagine a little girl holding hands with her mom at the air show, looking at the Snowbirds. And she’s saying, “Hey mommy, when I grow up, I want to be a pilot.” Her mom says, “Yes honey, that’s a great job for you — you’re going to be great.” If we can convince the mothers to encourage their daughters — and their sons — to join the military, that would be great. Particularly young ladies ages eight to 12 – if we can give them the knowledge and excitement of what we do, we can give them the spark to succeed. Any girl can be a great pilot if that’s truly what they want.

The newly-appointed Brigadier-General Bourgon salutes during her formal ceremony in April 2015.

IC: Women are often intimidated by male-dominated fields such as aviation. What would be your advice to a young woman who is considering a career as a pilot?

LB: We have to stop second-guessing ourselves; women can do anything they want. The sky is not the limit — there are no barriers. The barriers that we perceive are in our own head. I think women are the worst at saying to themselves, “No, I can’t do that — I’m not good enough.” Men and young boys will try everything; they don’t mind failing as much as women. Women tend to see failure as a big thing, where men see that they tried and failed and they’ll try something else. Women need to be told again and again, “Yes, you CAN do it — give it a try! If you like it great, if not, you didn’t lose anything — it’s called experience.”

I think it’s about discovering who you are — your strengths and weaknesses, and attempting stuff that is a little bit scary. Scary is OK! I always tell my daughter; butterflies in your stomach are normal, and they’re going to go away. You have to push once in a while to get outside of your comfort zone. I think it’s about discovering, it’s about exploration, it’s about having fun — living on the edge a little bit, and choosing to never stop learning.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)