Representing accessibility in the Ingenium collection

Historian Anna Whitelock once said, “Studying history is the ultimate passport to the future.” Her quote reminds us that in many contexts, history teaches us to move forward, recognize mistakes, and learn from them.

This pearl of wisdom provides us with a framework to examine how accessibility is showcased through the collection at Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation. It’s important to note that historically, when we present accessibility collections in a museum setting, the viewpoint is often from medical institutions.

First of all, I believe we need to broaden our overall view of accessibility. In a number of the exhibitions at the Canada Science and Technology Museum, there are narratives about individuals who became disabled — due to illness or accident — and used technology to triumph over new barriers in their lives. While I understand the importance of highlighting these barriers and their solutions, I feel these narratives can lean towards presenting disability as a problem that needs to be “fixed.” As a member of the disabled community, I think the view of accessibility as a triumph over disability is limited and limiting at best.

By adding new narratives that showcase the stories of individuals who were born disabled — and who possess unique talents and abilities — we can contribute to overcoming stereotypes around disability, while accommodating and celebrating the disabled community.

Secondly, the collection could be expanded to include a broader representation of accessibility artifacts. Currently, a large part of the collection on display at the museum focuses on mobility accessibility (such as prosthetics and adaptive vehicles) and age-related accessibility. Technologies developed for the deaf and blind communities (such as braille) are also represented. However, the collection does not represent disabilities related to neurodiversity, such as autism, attention deficit disorder, and dyslexia, to name a few. While these are often thought of as “invisible” disabilities, there are concrete ways to incorporate them in our collection. To represent dyslexia, for example, a software program — such as the HelperBird text-to-speech app — could be added to the collection. This would complement the collection by showcasing technologies that dyslexic individuals rely on in their everyday lives.

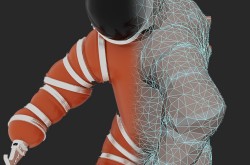

Finally, the museum needs to continue the effort to shift to a more human representation of accessibility. This means acquiring objects that showcase the individual experience of living with a disability. For example, museum curator Tom Everrett collected a number of aesthetic coverings for prostheses. Created using a variety of bright-coloured, patterned plastics, these coverings have no medical value. Instead, they offer disabled individuals the opportunity to express their unique personalities by decorating their metal and plastic prostheses.

As we look ahead to the future of our national science and technology collection, I am hopeful that we have started to make a critical shift in how we represent accessibility. It is only by moving past the representation of disability as a medical misfortune that we can lift up the extraordinary individuals who make up the fabric of our culture. By bringing to light a more holistic and true representation of accessibility, we can move towards a more progressive, inclusive, and informed society.