Re-examining Archival Research Following the COVID-19 Pandemic

Re-The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a laundry list of consequences on everyday life; a list far too long to synthesize into one tidy blog post. Instead, I want to shine a light on the impact that the pandemic has had on archival research. For much of the last two years, physical archives have been closed to researchers. For example, the University of Toronto’s archival collections have been shuttered for in-person use, while their online collections and services have remained accessible. This shift to online access, despite being necessary and justified, has had a notable impact on academic research. Like many of my fellow students, during the pandemic I shaped my research around what was available through online archives. I thought myself well versed in navigating the cumbersome Library and Archives Canada interface, the captivating digitized photographs of the Toronto Public Library, and the virtual shelves of the University of Toronto’s Robarts Library. Although this online research is incredibly valuable, many institutions have not digitized their collections which has meant that, over the course of the last few years, these sources have not informed our scholarly analysis of the past.

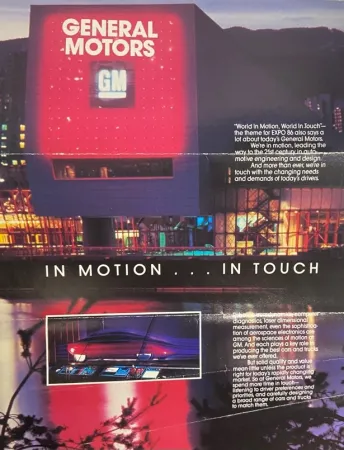

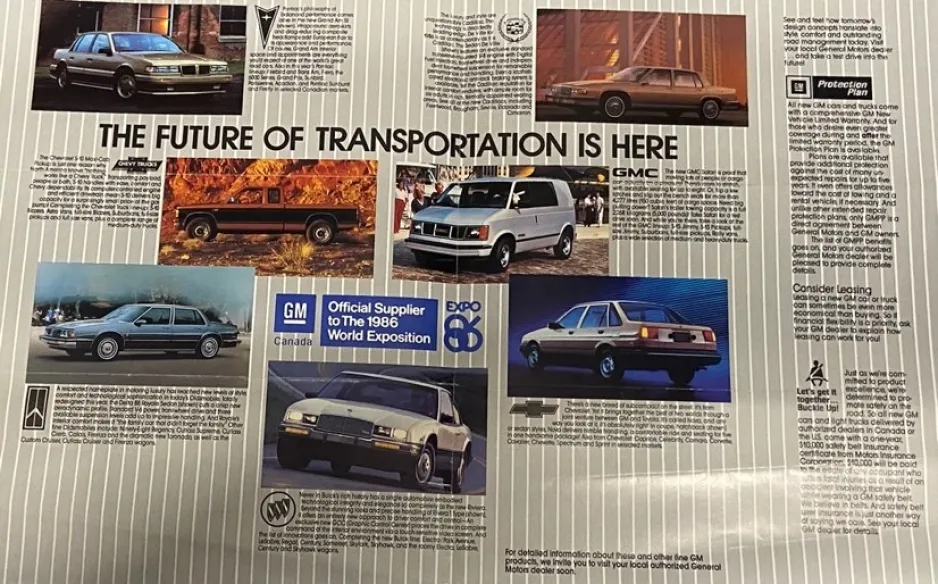

Through the Ingenium-University of Toronto project “Contesting Closure: Life Stories of Work and Community in Oshawa’s Motor City, 1980-2019,” we travelled to Oshawa for an intensive research visit. Our day began with a tour of the Oshawa Museum. In the afternoon, a few members of our research team conducted oral history interviews with former GM Oshawa employees and I investigated the archives held at the Canadian Automotive Museum. Upon entering the archival collection’s room, the first thing I noticed was that history is, in fact, messy, as clichéd as it sounds. My only other encounters with in-person archival research had been to look at specific documents I knew were there. Instead, my search at CAM consisted of navigating through hundreds of boxes of documents, a mix of categorized and uncategorized material. Unlike the digital archives, there was no keyword to input to get me started. I opened a box, went through the contents, and moved onto the next box. I found things that did not relate to our project or our timeline. I also found material that provided new insights into our project. For example, prior to the trip to Oshawa, I had read about GM’s plan to respond to the forces of globalization and autonomation through implementing a “Factory of the Future” automotive production strategy. While in the archives at the museum, I found a GM pamphlet for Expo 86 that stated “The Future of Transportation is Here.” This pamphlet is material evidence of the implementation of a corporate strategy; it’s an incredibly rich primary source!

In reflecting on this experience, I’m struck by the ways in which an archive can allow for a physical connection with history. By actually interacting with these physical documents, I was able to connect my previous research to real, tangible evidence of past events. I could have, and am sure I will in the future, spend hours in the archives.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!