Honouring the brave: David Ernest Hornell and the heroic sinking of a German submarine

David Ernest Hornell was born in Toronto, Ontario on Jan. 26, 1910. Known to be an athlete, he enjoyed playing sports like rugby and tennis. Hornell proved himself to be an exceptional student, and received a scholarship intended to ensure that he continued his education into university. However, due to the economic circumstances of the 1930s, he was not able to pursue his education; he took a job working for Good Year Tire instead. Hornell was active in his community, and taught Sunday school at the Wesley United Church. His early life indicates a hard-working and well-rounded young man, qualities he would bring with him into his military career.

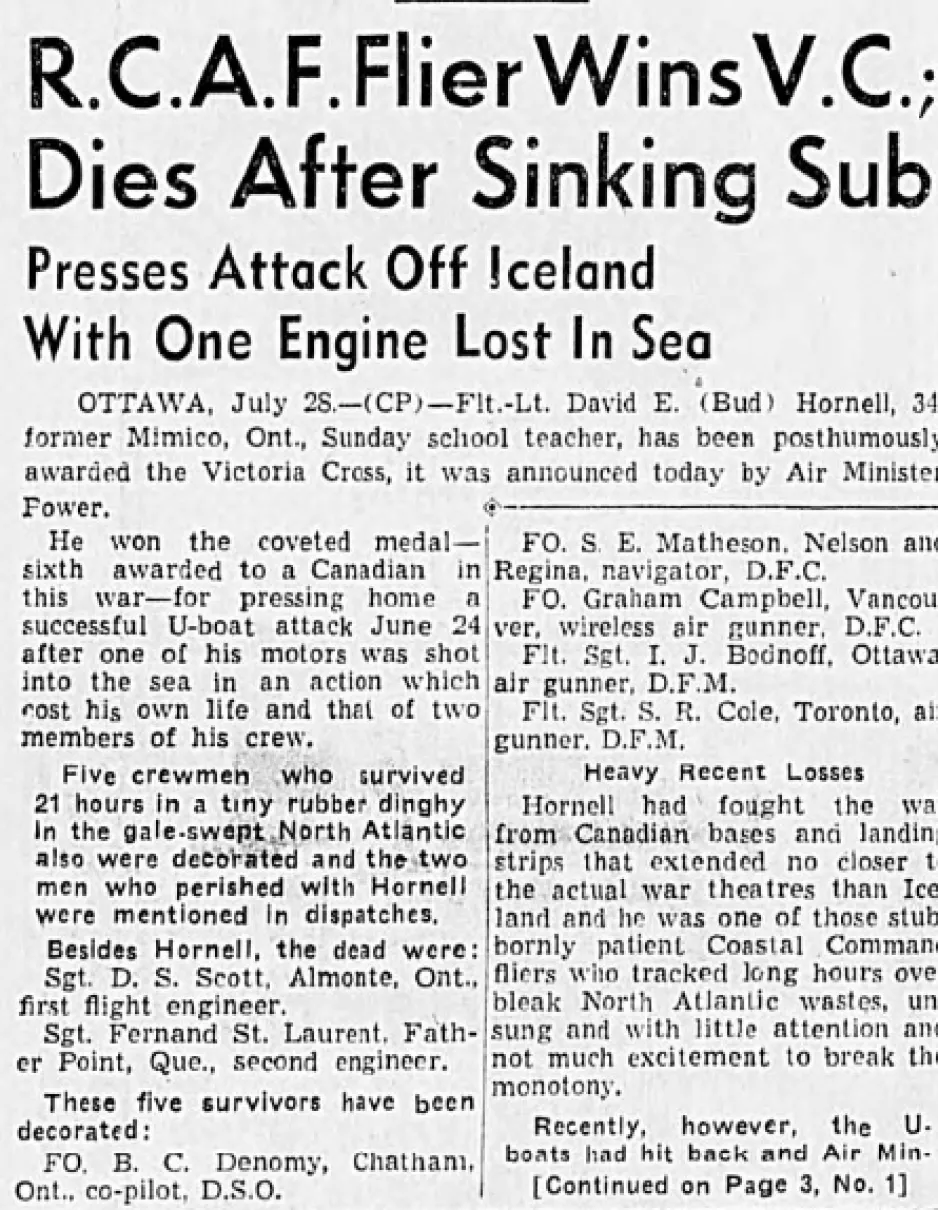

Hornell joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) in early 1941, at the age of 30. Soon after, he was flying solo. Hornell received his pilot wings in September. Although older than the other Second World War Victoria Cross recipients mentioned throughout this series, Hornell served with the determination of any younger airman. Hornell was first stationed in Nova Scotia with No. 120 Squadron, RCAF. The squadron’s objective was to patrol the Atlantic coast, looking for German submarines. During the Second World War, German submarines were known to patrol these waters, looking for unsuspecting ships making crossing the Atlantic, to and from Europe. Hornell was later assigned to No. 162 Squadron, RCAF. There, he continued the work he was doing with No. 120 Squadron, except now he was stationed in the middle of the Atlantic in Reykjavik, Iceland. Hornell was eventually sent to Northern Scotland with the other members of his squadron, to play both a defensive and offensive role — patrolling for submarines. During these patrols, Hornell was flying an amphibious aircraft; the Consolidated PBY-5A Canso A was capable of landing and taking off from both the water and the ground, making it suitable for these kinds of sorties.

An article from the Winnipeg Evening Tribune, detailing Hornell’s final moments and highlighting his posthumous award.

Duelling with a submarine

On June 24, 1944, Hornell was finishing up a 12-hour patrol in the North Atlantic when he and his comrades noticed a surfaced submarine. According to a citation published in the London Gazette, they engaged the submarine. The crew of the submarine met them with heavy anti-aircraft fire, dashing all hopes of a surprise attack. Trading shots back and forth, the damage to Hornell’s aircraft became more severe. Despite the enemy anti-aircraft fire, Hornell was able to release the depth charges his aircraft was equipped with. The charges were dropped in close enough proximity to the submarine to successfully sink the vessel, but the damage to the aircraft was too severe; fires had broken out across the aircraft in multiple places, including the wing.

Hornell made an emergency landing in the ocean. While the aircraft had turned to little more than flaming wreckage, now the crew had a whole new enemy to deal with: they were plunged into freezing cold water, far from shore. This proved to be a fatal adversary for some of the crew as they awaited rescue in the North Atlantic. Since their single life raft was too small for eight crew members, the men took shifts hanging on to the side of the raft. The crew had to endure 21 hours in the freezing water before they were rescued. Although they were spotted in the water by a Norwegian Catalina Flying Boat from Squadron No. 333, the weather and waves made it extremely difficult for rescuers to secure them. While suffering from the freezing conditions, Hornell selflessly volunteered himself to swim to an airborne lifeboat that had been dropped nearby for the crew. Unfortunately, two crew members died from exposure during this time; Hornell would later succumb to exposure as well.

Remembering a brave fighter

This is the Consolidated PBY-5A Canso A, pictured outside of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa. This aircraft is currently part of Ingenium’s collection although it is stored in the reserve hangar and cannot be regularly viewed by the public

Hornell was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions throughout this ordeal. Not only was he and his crew able to successfully down a submarine in an aircraft that was surely becoming a death trap, but he also demonstrated superb bravery and selflessness while he and his crew awaited rescue from the freezing water.

Unlike Ian Willoughby Bazalgette and Robert Hampton Gray, Hornell did not end up having a mountain named after him. That’s not to say that he isn’t remembered through other important memorials to this day. In his hometown of Toronto, a public school was named after him — down the shoreline from where he was born — and Toronto's 700 David Hornell V.C. Royal Canadian Air Cadet Squadron was named in his honour. A PBY Canso with the colours and markings of No. 162 Squadron — including call number 9754-P, the call number of the plane Hornell flew on his last flight — was restored and dedicated to Hornell by the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum, located in Hamilton, Ontario. Hornell’s medals can be seen at the 1 Canadian Air Division Headquarters Museum in Winnipeg, Manitoba.