Food for the future: How Canada's seed bank is protecting crop plants for tomorrow

Plant biodiversity is essential for sustainable food production and climate resilient farming, but this biodiversity is disappearing due to human activity. That’s why organizations around the world are collaborating to maintain a giant library of plant seeds and cuttings, in a network of plant gene banks. This ensures the genetic diversity of our food crops — and their wild relatives — will still be available to us in the future.

Renée-Claude Goulet, Science Advisor for the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum in Ottawa, Ontario, visited Plant Gene Resource of Canada (PGRC) in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan in 2016. She brings you a behind-the-scenes look at her visit to Canada’s plant gene bank, and examines the role Canada plays in the global endeavour to ensure crop biodiversity. Through her photos and story, you’ll get a glimpse of how scientists and their teams collect, store, study, multiply, and share seeds around the world.

Why a plant gene bank?

For over 10,000 years, we humans have had a hand in the evolution of the plants we eat. By selecting plants with desirable traits and replanting their seeds, our ancestors shaped the crops we know today. The initial domestication of plants was an immense cultural achievement, and today’s crop biodiversity represents a rich, common heritage. These days, advanced breeding techniques and technologies allow us to fine tune these cultivated plants, by creating new crop varieties targeted to our needs.

As the Earth’s climate changes, farmers face more extreme weather patterns and shifting ecosystems. This can bring about losses and even crop failure, due to drought, flooding, pests, and diseases. One way to help farmers overcome these challenges is by providing them with crop varieties which are better adapted to the local conditions, and the specific challenges they may face. This can be achieved by breeding improved versions of our common crops, using specific genetic traits found in gene bank collections. It can also be achieved by reviving ancient cultivated plants or rare “strains” of our food plants.

In order to keep improving crops, breeders need breeding stock — that is, parent plants containing interesting gene variations. Some of the genetic traits needed for making a crop more tolerant to attacks from a certain pest — or more nutritious, for example — may be found in its wild counterparts. The variant may also be found in long-gone family lines of the crop, or in an isolated population collected in a farmer’s field halfway across the world. This is one of the reasons we need plant gene banks.

Recognizing the importance of preserving plant biodiversity for food security and future breeding efforts, many countries are cooperating in a giant, long-term science project: to collect, study, preserve, and utilize the genetic diversity of our domesticated plants and their wild relatives.

Hosted by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), PGRC is part of a worldwide network of gene banks that collect, preserve, study, increase, and distribute plant germplasm. This is the plant material that contains genes, which can be used to grow a new plant. Their work ensures we have a “backup” of our plant biodiversity for food and agriculture, and that we can have access to the precious genetic diversity of domesticated plants for the foreseeable future.

The PGRC was established in Ottawa in 1970, on the AAFC Central Experimental Farm, in an inconspicuous building right next to the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum. Today, there are three “nodes” in the collection, each with their own specialization:

- Fredericton, New Brunswick: Potatoes

- Harrow, Ontario: Fruit trees and small crops (eg, apple and strawberry)

- Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: All seed germplasm (cereals, crop wild relatives, horticultural plants) including the Crucifer node (eg, canola, mustard, camelina)

You may wonder what it looks like inside a gene bank and how it all works! Come along as I share some highlights from my visit to the PGRC in Saskatoon in June 2016.

We visited the AAFC Saskatoon Research and Development Centre in Saskatchewan — where Canada’s seed bank is maintained.

Gene banks around the world share the work of conserving our plant biodiversity for food and agriculture. Canada’s gene bank is responsible for maintaining the world’s base collection of barley and oats, and a copy of the world’s collection of pearl millet, oilseeds, and crucifers.

The vaults at this location contain over 115,000 unique samples — or accessions — of seeds.

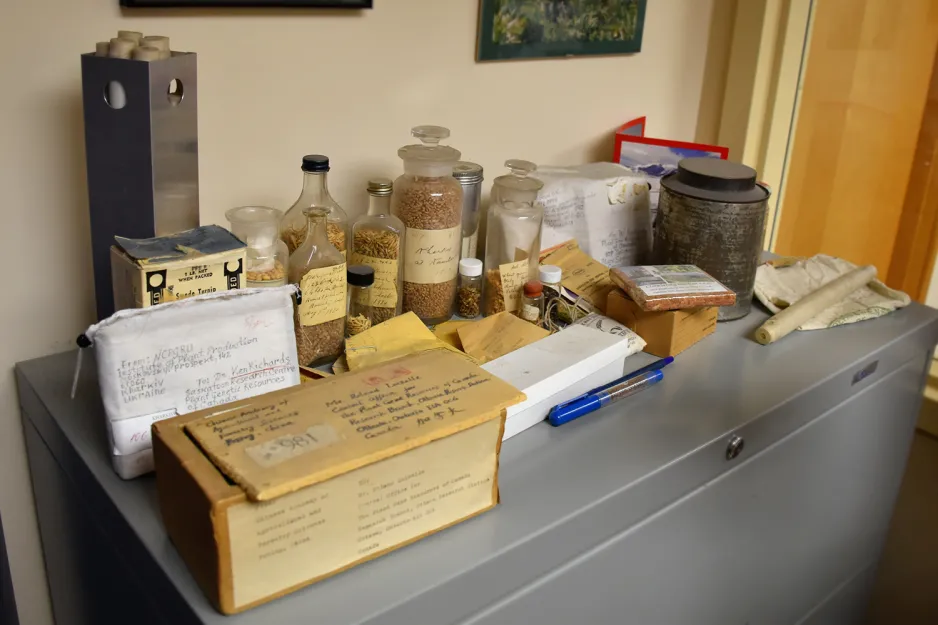

A display of various seed containers collected by the Plant Gene Resource of Canada.

In the office area, I was drawn to this interesting display of old bottles, seed envelopes, and shipping boxes with return addresses in China, Ukraine, and other international locations. The PGRC receives seeds from around the world, and also collects them from plant breeders locally, from other gene banks, and on collecting trips.

In the lab

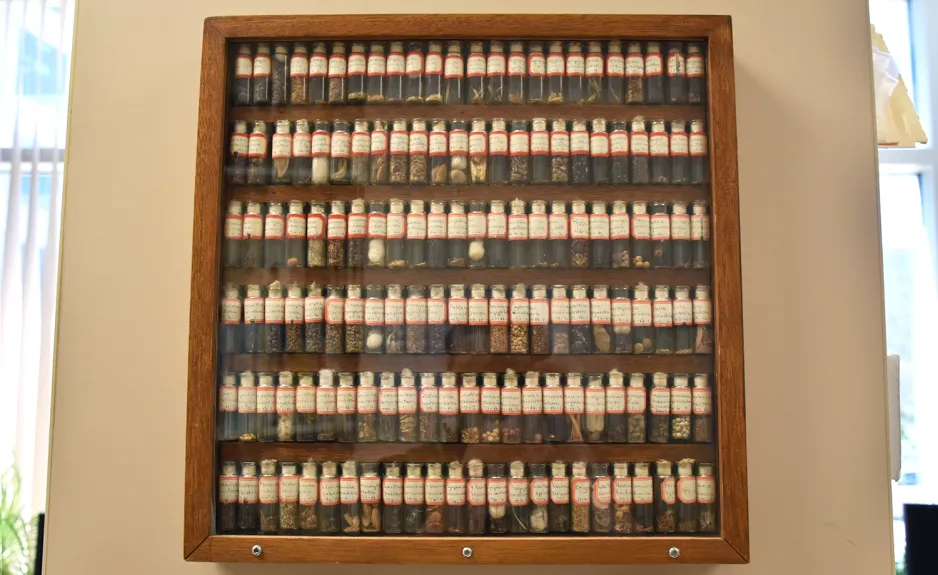

A wall display of seeds in vials in a Plant Gene Resource of Canada lab.

Entering one of the labs, another piece caught my eye — 144 unique seed samples beautifully displayed (they aren’t part of the actual collection). You can tell the people working here have a true appreciation for the beauty, diversity, and history of seeds and plant breeding.

When requested, seeds are taken out of storage, and sampled out into envelopes to be sent off.

An important part of the work at the PGRC is to process requests for samples of seeds stored in the gene bank. Anyone with a valid use can ask for samples, but typically requests come in from researchers, breeders, private companies, other gene banks, and seed-saving programs where enthusiasts can help preserve our crops’ genetic heritage.

The seed vaults

A look inside a medium-term storage vault at the Plant Gene Resource of Canada.

We enter one of the three seed storage areas, basically, a big cold room. In this medium-term storage vault, “in transit” seeds are kept in paper envelopes at four degrees Celsius, and 20 per cent relative air humidity. New samples added to the bank stay here for 30 days before they go off for long-term storage.

Every sample is labeled with a barcode and tracked in a computer database.

Packages of “male sterile barley” seeds await their turn for multiplication.

Seeds won’t be viable forever, and since they’re shared with people around the world, samples can run out. So each accession — or unique sample of seed in the gene bank — eventually gets grown out, so that new seeds can be harvested. This freshens up and replenishes the supply.

A view into the long-term storage vault at the Plant Gene Resource of Canada.

In this long-term storage vault, dry seeds sit in laminated, air-tight envelopes at -20 degrees Celsius. Seeds can quickly deteriorate when exposed to light, water, oxygen, living critters, and changing temperatures, so this room provides a stable environment where conditions are just right for long-term storage. Some of the seeds in here could still be viable centuries from now.

The greenhouses

Plants growing and maturing in the greenhouse at the Plant Gene Resource of Canada.

After the storage vaults, we step into the greenhouses. The PGRC staff grow seeds in the greenhouses when plants have specific needs or life cycles that make it impractical or impossible to grow in a field. Sometimes they just don’t have a lot of seeds to start with, and need to carefully tend to the few they can grow.

When researchers grow samples from the collection, all sorts of interesting forms and shapes emerge.

In the greenhouse and fields, breeders, researchers, and gene bank staff work together to study the plants closely. They document, describe, and catalogue the crops they grow to build up the information for each of them, which is made available on the PGRC website.

A cart in the greenhouse holds samples of Barbed goatgrass (Aegilops triuncialis) from Iran and Turkey, and Emmer wheat (Triticum dicoccon) from Manitoba and its wild relative (Triticum dicoccoides) from Jordan.

On our way out of the greenhouse at the end of our tour, this little station perfectly illustrated how collecting crop plant biodiversity is part biology, part geography. The majority of our crops were brought to Canada. This means many of these crops’ wild and cultivated relatives are found in the places where they first originated. And here, in the greenhouse, they’re brought back together to be saved for another day.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the kind folks at the Plant Gene Resource of Canada in Saskatoon for giving us this fascinating tour of the installations, and for their contributions to this article.

Go further

Visit the links below for more information about the global effort of conserving plant germplasm.

- Video: Plant Gene Resources of Canada: Our Investment in Biodiversity and Sustainability

- PGRC Website: Plant Gene Resource of Canada

- FAO International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture

- FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture

- Government of Canada: Plant genetic resources for food and agriculture - international treaty

- Convention on Biological Diversity: Agricultural Biodiversity

- History of Agricultural Biotechnology: How Crop Development has Evolved