3 things you should know about living inoculants, space debris, and an ocean of plastic waste

Meet Renée-Claude Goulet, Cassandra Marion, and Ellen Morrison.

They are Ingenium’s science advisors, providing expert scientific advice on key subjects relating to the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum, the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, and the Canada Science and Technology Museum.

In this colourful monthly blog series, Ingenium’s science advisors offer up three quirky nuggets related to their areas of expertise. For the May edition, they examine a new product that could give your garden a boost, the growing issue of space debris, and the urgent need to address plastic waste in our world ocean.

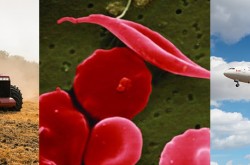

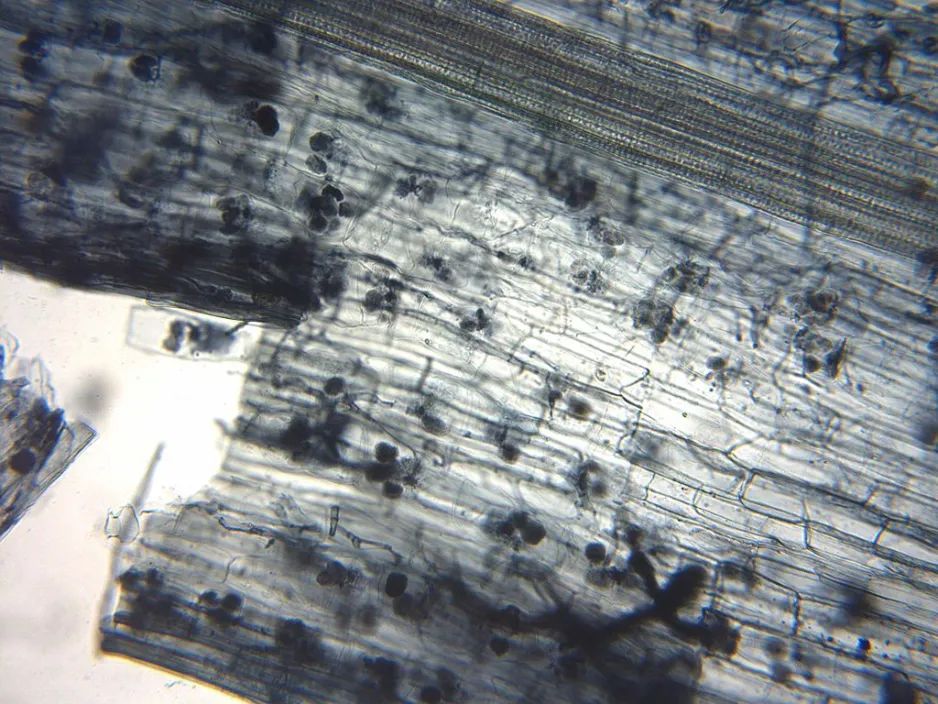

Mycorrhizal fungi is microscopic. Structures called arbuscules form in the cells of plant roots like this flax, seen under the microscope.

A secret mushroom-plant connection can help your garden

In recent years, gardeners might have noticed a new product on the shelves at garden centers: living inoculants for soil, containing “mycorrhizae.” Not only can we buy packaged inoculants, but more and more potting soils have started including it in their mix. So what’s the deal with these mycorrhizae things and why are they becoming so popular?

The inoculant packets contain spores — the mushroom version of seeds — of a type of soil fungus called arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, which forms mutually beneficial relationships with plants’ root systems. This type of plant-mushroom symbiosis occurs in an estimated 85 per cent of land plants, and is one of the most important, yet unseen, plant-soil connections. Though there are spores naturally found in the soil, inoculants allow us to beef up their numbers.

Named after the Greek words for mushroom (mykes) and root (rhiza), this type of microscopic fungus grows a little “puff” inside the cells of plant roots. It then extends long filaments out into the soil — effectively increasing the underground reach of the plant — and plugging it into a vast communication network. These microscopic filaments mine the soil for nutrients, and bring them to the plant. They also provide water, and offer some protection against stressors like drought and pests. In return, plants feed the fungus with sugars made through photosynthesis.

In agriculture, there’s a growing interest in harnessing soil biology to achieve better yields, while reducing environmental impact. Researchers are studying the potential of using bacteria and fungi to reduce the need for fertilizers and pesticides. To date, a growing roster of inoculants are available for farmers — and the outlook is promising.

Since this is all pretty new, we know relatively little about the long-term effects and efficacy of adding mycorrhizal fungi to agricultural soils. Recently, researchers at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada found that survival of inoculated mycorrhizal species depended on specific soil environments. This means that the solutions are not “one size fits all”, and results may vary across agro ecosystems.

Research is also revealing that fungal relationships in the ecosystem are even more complex than we first thought. For example, researchers from the University of Ottawa found that plants may actually influence the genetics of mycorrhizal fungi that associate with them. Thus, the same inoculant might have different results when used on different species of plants. Another recent study by researchers from Boyce Thompson Institute indicates that fungi might even have a microbiome of their own, specific bacteria allowing them to access nutrients like phosphorous and nitrogen.

This is an exciting field to follow, as we discover more about the interconnectedness of the world on our path to more sustainable, productive agriculture. Until we know for sure how these inoculants size up, it never hurts to do your own backyard experiments — to see if you can power up your gardening with fungi!

By Renée-Claude Goulet

A recent space debris shower, from a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket’s second stage breaking up over Oregon, was caught on video by an observer.

Space debris: Yes, you should be concerned.

If you think your Wi-Fi is spotty now, be warned: Space debris has the potential to make things even worse.

Human-made junk orbiting the Earth is an ever-growing problem for the space industry, astronauts, and anyone living in the modern world. Space debris consists mostly of discarded rockets stages, inactive satellites, and unidentified fragments which can explode, collide with other objects, and eventually deorbit and fall to Earth.

The number of working satellites in orbit — 3,372 as of January 2021 — is increasing dramatically. These satellites share their orbit with approximately 129 million debris objects, each larger than a millimetre. Of those, 26,000 of the larger objects are being tracked and monitored from the ground; collision warnings are issued frequently to enable a working spacecraft to adjust its orbit to dodge the debris. At speeds up to 56,000 km/hr, even the smallest fragment can damage or destroy a satellite. In fact, several collisions have already occurred, such as the 2009 collision between a functional Iridium telecommunications satellite and an inactive Russian satellite.

The International Space Station, which orbits lower than most satellites, has already been hit by small fragments and has had to conduct some 25 collision avoidance maneuvers while astronauts bravely ‘shelter in place.’

Last month, the second stage of a SpaceX rocket broke up spectacularly in the evening sky over western Canada and the United States. It failed a de-orbit burn, which would have directed it to safely enter the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean. Uncontrolled entries are not uncommon, and this recent event was yet another reminder of the space debris crowding low Earth orbit (less than 1,200 km from Earth’s surface).

Today, our modern way of living depends on a number of satellite services that collisions could disrupt or obliterate! These include cellular, internet and television network communications, weather forecasts, Earth observation information during disasters, GPS navigation and climate and environmental monitoring.

The worst-case scenario would be a cascade of collisions that creates a global debris cloud so dense it would render low Earth orbit unsafe and inoperable for generations. Active intervention and international consensus are needed to address this ever-increasing global problem.

The good news is the Inter-Agency Space Debris Committee, now consisting of 13 space-faring nations, adopted a consensus set of mitigation guidelines endorsed by the United Nations. Mitigation strategies include: developing technologies for automated collision avoidance, methods for extending the lifetime of satellites in orbit, debris removal techniques including capturing debris and sending it to burn up in the atmosphere or moving them to a graveyard orbit, and regulations for the proper decommissioning of satellites.

The first debris removal missions are in the works, including ClearSpace-1, recently commissioned by the European Space Agency to launch in 2025. Let’s hope these strategies are effective and support the safe and sustainable use of outer space in the future.

Go further

- The European Space Agency just hosted a major space debris conference and campaign

- Read about Canada’s role in tracking and de-orbiting space debris

- Check out NASA’s Debris Mitigation site

By: Cassandra Marion

An ocean of plastic: How you can help

Our global ocean — which encompasses five interconnected ocean basins — is vital to our planet. According to the National Ocean Service, it produces over half of our world’s oxygen and absorbs a huge amount of carbon from the atmosphere. The ocean helps regulate our climate, by transferring heat from the equator to other areas of the planet. We also rely on the ocean for transportation, food, and ingredients for medicinal products. Despite these incentives to keep our ocean healthy, we flood it with nine million tonnes of plastic every year.

What happens to our plastic?

In Canada, we recycle only nine per cent of our plastic waste; about 86 per cent ends up in a landfill, and five per cent is burned for energy production (or is simply litter). Unfortunately, even the plastic that is disposed of in a recycling bin may not be recycled, due to contamination. In Ottawa, the blue bins picked up by the city-run curbside program have a 16 per cent contamination rate — mostly due residents adding plastic bags, which are not accepted.

Plastics don’t decompose in the same way that organic materials do. Organic materials — like wood and food — are transformed by bacteria. These organisms aren’t so interested in plastics. Instead, plastics can be broken down by UV rays. However, unlike organic materials, plastics aren’t transformed into useful compounds. Instead, the UV rays break down large pieces of plastic into many smaller pieces…which leads us to the next issue: microplastics.

How long does it take for plastic to decompose?

Plastic bags: 20 years

Plastic straws: 200 years

Plastic water bottles: 450 years

Coffee pods, disposable diapers, and plastic toothbrushes: 500 years

Microplastics are small pieces of plastic which are too small to be filtered out by water treatment facilities. These can include microfibers from plastic-based clothing, and pieces of larger plastic that has broken down into smaller pieces.

What’s the problem?

While some plastics are made from plants, 90 per cent come from fossil fuels. Recycling one tonne of plastic prevents up to two tonnes of carbon pollution. Incineration of plastics releases even more carbon into the atmosphere.

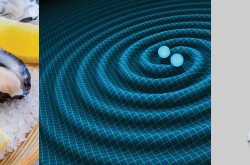

In our oceans, marine animals can eat, choke on, or become entangled in marine plastics. Some animals mistake plastic waste for prey — then starve because their stomachs are filled with plastic. They can also suffer injuries and infections caused by marine plastic. Tiny plastic particles can be found in tap water and in seafood; the chemicals present in these particles pose a health hazard for animals and humans who ingest them. They may be carcinogenic and interfere with the body’s endocrine system.

What can I do?

Consider adopting these habits to help keep our ocean clean:

- When able, avoid single use plastics (plastic bags, cups, cutlery, and bottles)

- Keep re-usable plastic alternatives handy

- Buy products that minimize plastic packaging

- Bring re-usable plastic bags when you shop

- Review your region’s recycling guidelines to ensure you’re recycling everything you can, and not contaminating the recycling with other plastics

- Join a shoreline cleanup

- Support initiatives dedicated to reducing single-use plastics

- Buy second-hand, and give away your old plastic-based items to someone who can continue using them