3 things you should know about fertilizer pollution, Mars, and the wandering albatross

Meet Renée-Claude Goulet and Michelle Campbell Mekarski.

They are Ingenium’s science advisors, providing expert scientific advice on key subjects relating to the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum and the Canada Science and Technology Museum. Jesse Rogerson, formerly the science advisor for the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, continues to lend his expert voice to the Channel.

In this colourful monthly blog series, Ingenium’s past and present science advisors offer up three quirky nuggets related to their areas of expertise. For the October edition, they discuss how technology is helping with fertilizer pollution, your chance to see Mars, and how the wandering albatross is helping to prevent illegal fishing.

Plants take nutrients from the soil, so these become depleted over time. Fertilizers allow us to provide field crops, such as corn, with the nutrients they need to grow.

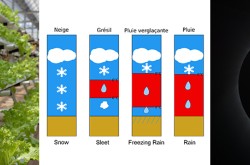

Farm technology is reducing fertilizer pollution

Composing 78 percent of the air we breathe and present in all living things, nitrogen is a key element for plant growth. Although there’s plenty of nitrogen in the air, it doesn’t dissolve in rainwater; so plants can’t take it up through their roots. Instead, they get it from decaying organic matter, and from soil microbes (and lightning!), which combine nitrogen from the air with other elements to create nitrate and ammonium — the two forms of nitrogen plants DO take up.

In the early 1900s, the Haber–Bosch process allowed us to transform nitrogen from the air into a form available to plants, creating fertilizer. Agriculture was revolutionized; we could now provide nitrogen to plants directly and increase agricultural productivity exponentially. But along with this came unforeseen environmental consequences, and the need to rethink our approaches.

The process to create nitrogen fertilizer has a large carbon footprint. Although plants need nitrogen in large amounts, their needs vary with time, weather, and soil. Excess nitrogen can quickly escape to the environment as a greenhouse gas — nitrous oxide or laughing gas — or leach into the water table.

Fertilizer pollution is a big problem that farmers and researchers are tackling together, across Canada and around the world. Some of the most promising solutions involve understanding exactly what crops need and when, and developing ways to provide them just that and no more.

Technology is helping us achieve this. For example, modern equipment that uses an in-tractor computer, GPS, and mapped field data to apply different amounts of fertilizer across the field — only where needed — provides more precision than ever before. Farmers now can reduce the amount of fertilizer applied while also reducing losses to the environment, while still maintaining and even improving yields.

Thanks to evolving agricultural research and technology, we can implement farming practises that benefit our food supply while protecting its most valuable resource: the Earth.

By Renée-Claude Goulet

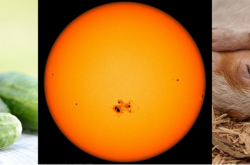

Mars gets its reddish hue from rust in the regolith (soil/rocks) that make up most of its surface.

Mars...in plain sight

On October 13, 2020, Mars will be closer to Earth than it will be for the next two years. This is an excellent opportunity to view the red planet, whether it's with a telescope, binoculars, or even just the naked eye.

Earth takes 365 days to orbit the Sun once, while Mars — being a bit further from the Sun — takes 687 days. Once every two years or so, Earth and Mars arrive at their closest approach to each other. Imagine it like the Sun, the Earth, and Mars fall into a line; the Sun is on one end, the Earth is in the middle, and Mars is at the other end. From Earth’s point of view, that means the Sun and Mars are exactly opposite one another in the sky, which is why we say Mars is at ‘opposition.’

As a result of opposition, when the Sun sets in October and November, Mars will start to rise. It will arch across the southern sky (if you live in the northern hemisphere) and set in the west, right about the time the Sun is rising. Since Mars is physically closer to us than normal, it will also appear to be slightly larger and brighter than normal.

While you look up at Mars this October, remember that the Perseverance Rover is currently en route to the red planet. The rover launched at the end of July 2020, and is expected to land on the surface, in Jezero Crater, in February 2021. Its mission: to search for evidence of past or present life, and to pick up samples of Mars to be returned to Earth at a later date. Canadian researchers at the University of Alberta and the Royal Ontario Museum are part of the teams that will help determine where Perseverance will retrieve samples from on Mars, and how to treat the samples when they return.

The next Mars opposition won’t be until December 2022, so make sure you don’t miss your chance to get a good look at one of our closest planetary neighbours this fall.

By Jesse Rogerson

How the albatross could report illegal fishing

Effective responses to environmental problems are often limited in terms of money, time, and the people required to implement them. So when a creative innovation takes flight, it’s particularly exciting.

Consider the problem of overfishing, which occurs when sea life is caught faster than it can replenish, leading to the decline of populations and species. Overfishing is often related to another serious problem: bycatch. Even though fishing vessels target a particular species, unwanted species often end up caught in nets or traps, too. Since bycatch generally cannot be used, this causes tons of unnecessary deaths of sea creatures — including endangered whales, turtles, and sea birds.

How does a nation go about limiting overfishing and bycatch? It requires a huge amount of resources to monitor fishing vessels and patrol the oceans. Unfortunately, due to the vast expanse of the world’s oceans, it’s relatively easy for illegal fishing vessels to escape monitoring and break laws regarding when, where, and how they catch fish. Especially when they venture into the open ocean, which is not under the jurisdiction of any single nation. So what’s the solution?

One answer might be the wandering albatross. These incredible birds have 3.5 m wingspans – the length of a small car — which carry them over 8.5 million kilometers during their lifetimes (that’s like flying to the Moon and back 10 times!). Albatrosses patrol vast areas of the oceans searching for fish, and some researchers have realized that this behavior could also be used to monitor illegal fishing.

Special data loggers attached to an albatross can be used to detect boat radar, which gives real-time data on boat locations. Initially, this data was used to reveal the flying and hunting patterns of albatrosses around fishing vessels. However, researchers realized that this data can be compared with data from the Automatic Identification System (AIS) to detect potential illegal activity. AIS is a system marine vessels use to detect each other and prevent collisions, and tends to be turned off if vessels want to avoid detection. In the Southern Ocean where the wandering albatrosses fly, this data has already provided an idea of the extent of illegal fishing.

Albatrosses have been severely affected by bycatch in the past; as they take advantage of fish being brought to the surface, it’s easy for them to get caught in nets. This has contributed to the threatened or endangered status of most albatross species. Now, these birds could collect the very data needed for their own conservation and survival.

By Michelle Campbell Mekarski