3 things you should know about pumpkins, Trojan asteroids, and embracing your inner zombie

Meet Renée-Claude Goulet, Cassandra Marion, and Michelle Campbell Mekarski.

They are Ingenium’s science advisors, providing expert scientific advice on key subjects relating to the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum, the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, and the Canada Science and Technology Museum.

In this colourful monthly blog series, Ingenium’s science advisors offer up quirky nuggets related to their areas of expertise. For the October edition, they discuss how selective breeding results in more choice at the pumpkin patch, a fly-by of seven Trojan asteroids, and why you need to embrace your “inner zombie.” Happy Halloween!

These pumpkins aren’t sick, they were bred to be bumpy! Plant breeding can be focused on modifying both functional and aesthetic traits.

Pick your pumpkin: Selective breeding gives us unlimited choices

It’s pumpkin season! Whether you enjoy carving a jack-o-lantern at Halloween or eating pumpkin pie at Thanksgiving, it seems pumpkins are synonymous with autumn. With a huge range of shapes, sizes, and colours, there’s a pumpkin for all tastes and purposes. What you may not know is that these options exist because of selective breeding.

A human intervention, selective breeding changes the traits of plants and animals over time. For millennia, humans have bred pumpkins to better meet our needs. Goals for improving pumpkins can include more fruit per plant, better flesh quality for eating, disease resistance, novel colour, size, shape, and texture.

Today, pumpkins are typically bred for specific purposes. Consider the oilseed pumpkin: this special variety creates seeds without a hull, commonly known as pepitas. Because the seeds don’t need the extra step of hull removal, they are preferred for making pumpkin seed oil (made by pressing the seeds), and to package for eating.

Selective breeding not only improves the aesthetic and physical qualities of the fruit, but also the horticultural traits of the plants. Ongoing work to breed pumpkins allows us to create varieties which might deal better with the effects of climate change. If we are able to adapt pumpkins to do well in new growing conditions and reduce losses from disease and pests, we can boost our food security and agricultural efficiency.

It's possible for anyone to breed their own pumpkin variety. In fact, that's how we inherited the heirloom varieties we have today. They are the work of gardeners and farmers of the past who kept seeds from their best plants, replanted them and cross-pollinated the offspring to eventually reveal a range of traits, thus creating new varieties. Giant pumpkins — famous for their unbelievable sizes reaching up to 1,190 kg — first came to be through backyard breeding.

As we look to a future filled with uncertainty, it will certainly be an advantage to have diversity in agriculture. And let’s not forget the simple joy variety brings for all of our fall carving, eating, and decorating!

By Renée-Claude Goulet

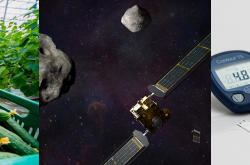

An artist’s concept of Lucy passing a Trojan asteroid.

Trojan asteroids may hold the keys to understanding our early solar system

For the first time in history, a spacecraft will launch towards the Trojan asteroids with the goal of gaining insight into the origins of our solar system.

NASA’s Lucy mission is scheduled to launch into space aboard an Atlas V rocket on October 16, 2021 from Cape Canaveral. It will take an estimated 12 years for Lucy to visit the Trojans — remnants of the early solar system — which act as rocky time capsules. To investigate these primordial materials, the Lucy mission will study and fly-by seven Trojan asteroids and one main belt asteroid, using remote sensing instruments to determine their surface characteristics, composition, and bulk physical properties.

The Trojans consist of two clusters of asteroids: one that leads and one that trails Jupiter in its orbit around the Sun. The asteroid clusters are located at about 60 degrees from Jupiter, in what are called Lagrange points, at just the right distance from both Jupiter and the Sun that their orbit is extremely stable. In these orbital “sweet spots,” an asteroid would be stable over billions of years — which is why scientists believe the Trojans to be the preserved remnants, or rocky fossils, of the formation of the outer solar system.

Lucy, NASA’s thirteenth Discovery Program mission, will take a complicated tour of the solar system to achieve its goal. First, it will fly-by the main belt asteroid dubbed Donald Johanson, after the researcher who discovered the Lucy fossil, to test drive its instrumentation. Then, Lucy will head to four Trojans in the leading swarm: Polymele, Eurybates, Leucus, and Orus. Finally, it will circle back to Earth for a gravity assist before heading out to a binary pair of asteroids in the trailing cluster, called Patroclus and Menoetius.

The variety of asteroids chosen to fly-by consist of all major types of Trojan asteroids. Some are similar to the icy bodies in the Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune, while others are more akin to the main belt asteroids between Mars and Jupiter. These investigations should give us a big picture understanding of the range of composition of these primordial materials, and the physical conditions billions of years ago.

The mission itself was named after the Lucy fossil, the skeleton of a female hominin found in Ethiopia which led to further understanding of human origins. Here, scientists hope the Lucy mission will give us insight into our solar system’s origins.

By Cassandra Marion

Without cellular regeneration, your body would wear out long before the end of your life. The key to survival is constant, carefully organized death on the cellular level.

Technically speaking, you’re part zombie

When’s the last time you stopped to consider your mortal state? You might feel pretty alive, but the mildly uncomfortable fact is you’re not TOTALLY alive. Your body is made of 30-40 trillion cells, but right now, billions of those cells are dying, already dead, or died before you were even born! A huge chunk of you has never been alive at all. Let’s face it: you’re part zombie.

Humans are made of cells, but that’s not all that makes up your body. About a third of your body is stuff that is made by cells, but not made of cells, so it’s not technically alive. For example, the liquid outside of your cells — such as spinal fluid, blood plasma, and mucus — makes up about 20 percent of your mass, but is not made of cells. The scaffolding that holds your body together, including bones, cartilage, and ligaments, is also mostly made of dead molecular material like proteins.

The remaining two thirds of your body is made of living cells, and about one percent of them will die today. We have about 200 different types of cells in our bodies, each with their own average lifespan:

- Neurons (the cells that form your brain and nerves) live just about as long as you do. Once your brain is done growing, what you have is what you’ve got. Very few areas in your nervous system can grow new cells, which is why brain and spine injuries are often so permanent.

- Muscle, fat, and bone cells stick around for a decade or more, though some have much longer or shorter lives. For example, about half of your heart muscle cells last your entire life, whereas the cells that helped grow the tiny bones in your ears were alive when you were in the womb, but died before you were even born.

- Red blood cells live about 120 days. Some white blood cells last only hours.

- Your nails, hair, and the outermost layer of your skin is already dead, and is continuously being replaced by the cells underneath. Every day you lose and regrow half a billion skin cells, which means in your lifetime you will produce enough dead skin to cover about a thousand bodies.

In the right balance, this cycle of death and regeneration in our bodies is critical for our health. Like a car, your body needs ongoing maintenance. So this Halloween, embrace your zombie side, because we’re all just squishy sacs of flesh that can only survive by being eternally rebuilt. How poetic is that?

By Michelle Campbell Mekarski

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!