The Hudson Strait Expedition: Looking beyond the prism of provenance

In honour of Archives Awareness Week (April 2-8), Ingenium is highlighting a few gems taken from our digital collection.

In archives and museums, history is often told through the prism of provenance. This could mean that the history of the artifact is told from the point of view of the manufacturer that made the object, or by the company that used the object. Similarly in archives, we most often present records from the point of view of their creator or the last person to use them before they were deposited with us.

Presenting records in this context can help us to understand a lot, but it can also blind us to some of the other stories that the records might be able tell. Let me explain this idea by taking a closer look at one of our collections in the Digital Archives.

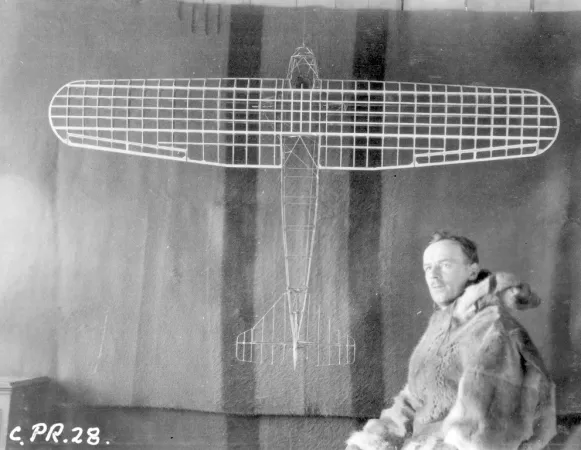

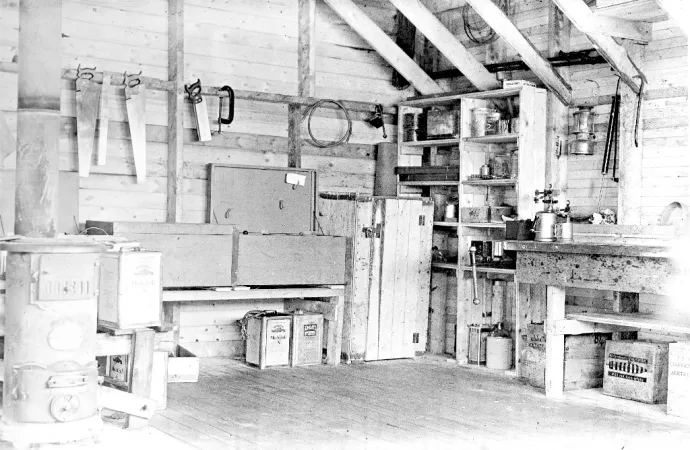

In 1927, the Hudson Strait Expedition set out on a mission to determine if the Hudson Strait could be used as an economical way of shipping grain to Europe. The expedition conducted aerial surveys, reported on weather patterns, and sought to find the best spot to end the extension of the railway line connecting to the proposed port. The members took photographs of their journey as part of their work; the resulting photograph albums that we have at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum have been catalogued as the “Hudson Strait Expedition fonds.” Fonds is the term we use in archives to describe records created by one creator. So, already we’ve made a decision to consider the “expedition” and its members as one creator.

Beyond the visual information in the photographs themselves, the only information in the fonds comes from the titles that were written under each image in the albums. Further understanding of the mission needs to come from reading the published report of the expedition (available in our library) or other sources, such as the National Film Board documentary, The Aviators of Hudson Strait.

But then if you have to look elsewhere to complete the story from the perspective of the expedition, why not also invest time and resources in telling some other stories? There are also individual life stories that could be told for each expedition member, including Inuit guides and camp helpers who are not named in the albums, report, or film. Other people – not on the expedition – were photographed as they conducted their daily lives. From the point of view of the expedition, they were sights or objects to be documented as part of the voyage.

As we work to add further information to the catalogue records in our Digital Archives, we hope to not stop at provenance – the creator’s point of view – by adding other keywords and relevant information. These archives live beyond the present purpose for which they were created, and could be made to tell more history where the story of provenance stops short.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)