Searching for the sublime: Algonquin Park and the origins of wilderness tourism

In the late 1800s, Canadian cities were in the process of a major transition due to great population increases, industrialization and a growing middle class. Toronto was no exception, and in terms of its population size and industrial production, was second only to Montreal in these years.

A great source of concern about the city came not only from industrial pollution, but also from the increased visibility of poverty and disease, and the evolution of transportation systems, most notably, the appearance of the automobile.

Another concern was that the modern, sedentary lifestyle, combined with dirt and congestion, had ill effects on both the physical and mental health of city dwellers.

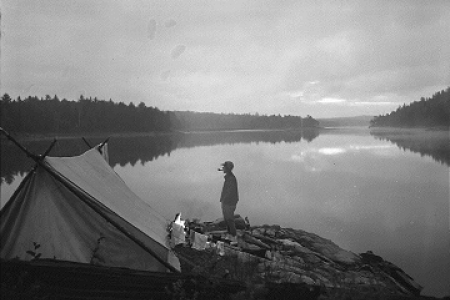

As the ill effects and social problems of Canada’s industrialized cities became apparent to an increasing number of people, many citizens sought relief through various forms of outdoor recreation. Wilderness vacations became increasingly popular for urban, middle–class Canadians in the late–nineteenth and early–twentieth centuries. Beyond their desire for simple respite from the pressures and problems of city life, their views were influenced by an established, largely Anglo–American cultural framework in which nature was associated with the idea of the sublime.

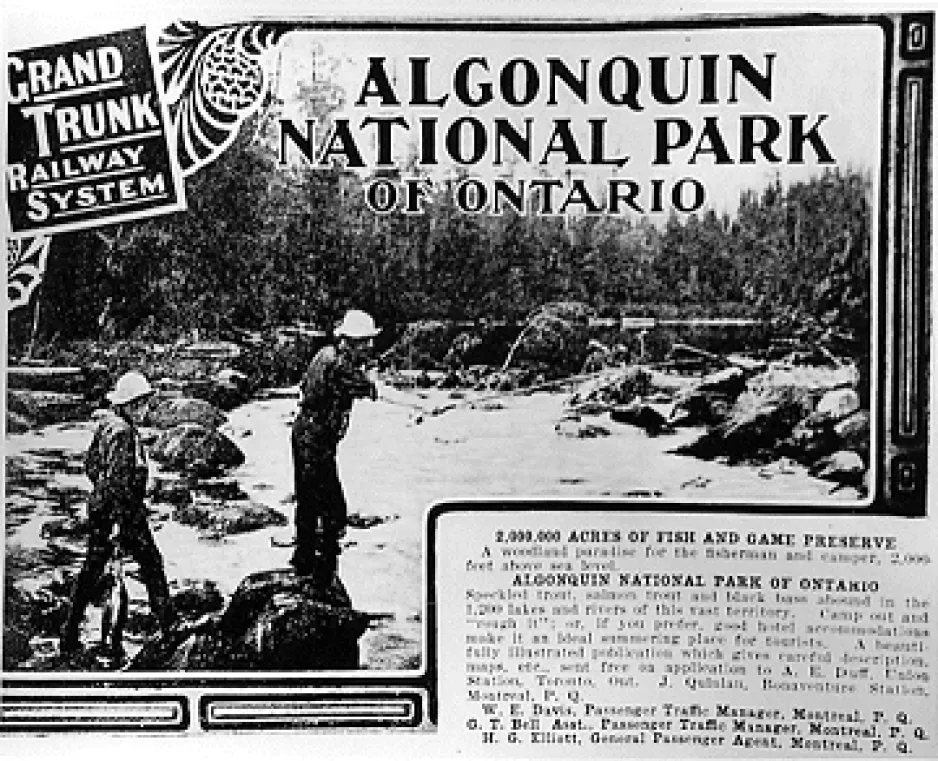

Although the construction of the railway had, in many ways, facilitated the creation of the modern industrial city, it was also the means by which citizens made their escape. The highway to Algonquin Park was not constructed until 1936, so until that date, the railway was the only means — aside from the canoe — by which people could reach the park. Both the Grand Trunk Railway and, later, the Canadian National Railway (CNR) actively promoted travel to wilderness destinations within Canada.

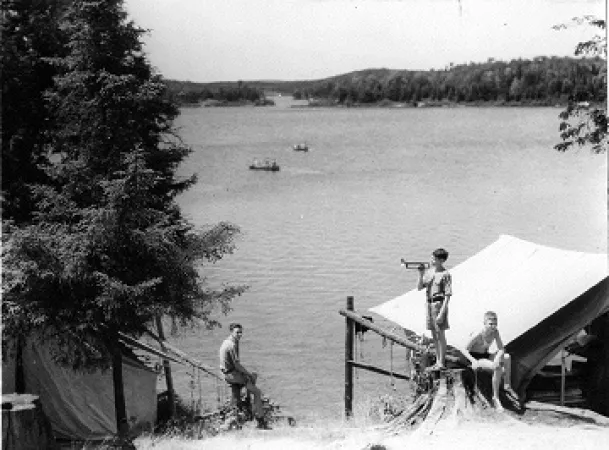

In the early twentieth century, the railway’s promotion of travel to wilderness destinations was extended to the building of hotels or lodges. In Algonquin Park, the CNR operated three lodges: the Highland Inn, Camp Minnesing, and Nominigan Lodge.

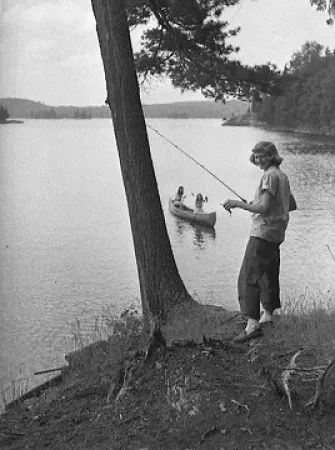

Upon arrival, the city traveler — be it young camper or adult vacationer — would also learn that Algonquin Park was a more permanent home to a small number of people, such as park rangers and guides. These “park people” and the shorter–term vacationer found that the park offered something appealing. Inspiration, independence, seasonal employment, a basic income, or simply peace and quiet and a good fishing hole – Algonquin Park offered all of the above to the increasing numbers of Canadians that discovered it during the twentieth century.

Adapted from an online exhibit from our Picturing the Past website.