Photos of the celebrated Avro Arrow plus...a disassembled vending machine?

In honour of Archives Awareness Week (April 1-7), Ingenium is highlighting a few gems taken from our digital collection.

Imagine what it might have been like to be a behind-the scenes, corporate photographer for A.V. Roe Canada. How interesting – and historically significant – it would have been to capture images of the incredible Avro Arrow, which was doomed to cancellation and destruction. What else would the corporate photographer have captured?

You won’t have to guess any longer, because the corporate photo collection for A.V. Roe Canada was recently added to Ingenium’s Digital Archives portal. We’ll talk about the photos in a moment, but first, let’s touch on the company’s history.

Hawker Siddeley, a British manufacturer, bought Victory Aircraft of Malton, Ontario, from the Canadian Government in 1945. It was renamed A.V. Roe Canada. The company developed or built the CF-100 Canuck, the C-102 Jetliner, and the CF-105 Arrow, among others. In 1962, A.V. Roe Canada was dissolved. In 1993, Hawker Siddeley Canada donated corporate photographs covering the A.V. Roe period to what was then called the National Aviation Museum.

There are three different series of negatives. The first, called the Numeric series, is now available in Ingenium’s Digital Archives. The Numeric series has the oldest photographs, but also extends right to 1961. The numbering of the series begins with 028006. It begs the question, were there earlier photographs that were not inherited by Hawker Siddeley? The first photographs date from the days of Victory Aircraft. They show men and women in military uniforms. They were taken by a photographer who left only the initials “G.B.” on the envelopes. Later photographs from 1945 were taken by “N.N.”, “Bev” or “L.G.”. These staffers are unknown contributors to the corporate memory for the time being. Through the Digital Archives portal’s collaborate button, we’re asking for the public’s help to solve such mysteries. These earlier shots are at least less of a puzzle when it comes to their content; the titles left by the photographer left on the envelopes are clear and descriptive.

![Lobby - [V & G] receptionist Guard & Driver in Lobby Groupe d'hommes et de femmes en uniforme derrière un bureau](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_2/public/2019-03/hs-28006-s.jpg?h=2ffd00db&itok=yNVx-BLj)

Later images have no titles, no dates, and no photographer listed. The only identifying feature is the number given to the negative. Here information has to be supplied by the archivist based on the photograph’s content, or from its context in the larger series of photographs. Such supplied information is presented in square brackets, so that users can tell what did or didn’t come from the original source material. On some occasions, the archivist did not have the time to research even a best educated guess and so left the photographs with the title [Untitled].

We decided to put one of our subject specialists, Erin Gregory, Assistant Curator for Aviation and Space, to the ‘untitled’ test. She analyzed two photographs shown below that had been called [Untitled] by the archivist at first. She was able to come up with titles, but it took some effort and time spent in the museum’s Library.

![[CF-100 18188, one of Avro's armament and evaluation CF-100s] Photograph of a CF-100 in flight](/sites/default/files/styles/inline_image/public/2019-03/hs-49754-s.jpg.webp?itok=neAQ3MWo)

The first step in any such exercise is to identify the airplane, and in this case, it is a CF-100 and probably an early Mk. IV. Next, I looked at the markings. The tail number is 18188. I noticed that while the CF-100 has RCAF roundels, it does not have a Squadron identifier nor does it have ‘RCAF’ painted on it. Perhaps the airplane, while destined for service in the RCAF, had not yet been taken on strength by the air force. That, coupled with an ad for Avro which featured the same tail number made me wonder if this particular CF-100 was a test bed or trial aircraft for the company. At this point, it’s time to hit the books. I consulted The Avro CF-100 by Larry Milberry and Canadian Military Aircraft by John A. Griffin. Milberry’s book has a photo of the same airplane and the caption indicates that 18188 was “one of Avro’s armament and evaluation CF-100s.” It was likely used for rocket firing trials. In 1954, it was taken on strength by the RCAF and struck off in 1958. Given that the photo is part of the Hawker Siddeley collection, it was likely taken sometime between 1952 and 1954.

![[Storeroom with Orenda gas turbine engine parts] Photograph of a storeroom with Orenda gas turbine engine parts](/sites/default/files/styles/inline_image/public/2019-03/hs-61929-s.jpg.webp?itok=0kOKO1uw)

This image is interesting and has a lot of different elements to it. Utilizing the high quality of the image to my advantage, I first zoomed in on the two boxes in the foreground and could clearly see the Orenda logo on both. The logo itself means that the image was taken after 1954 when Avro’s parent company, Hawker Siddeley, re-organized and Avro’s Gas Turbine Division became Orenda Engines. An end date is a little trickier to determine. The large box is a crate for a Display Engine and the smaller box is for Display Signs, so together they were likely brought to events or tradeshows. The image was definitely not taken in either of those contexts, so they are likely in storage in the photograph. In the midground there are dozens of what appear to be combustion chambers used in Orenda engines. The combustion chambers have what could be inspection tags attached to them. The shelving units in the background of the photograph appear to house various parts and components. So, the image is likely of a storeroom but as Orenda had two facilities (one at Malton and one at Nobel), it is impossible to tell where this particular storage area was located.

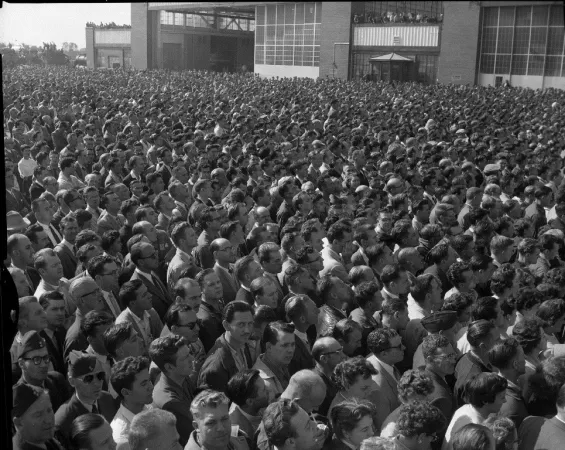

The daily work of the corporate photographers at A.V. Roe Canada ranged from the mundane to the sublime. A corporate photographer had to take the passport photographs of A.V. Roe’s staff members. They also had to take photographs of…a disassembled vending machine? That is what it looks like to the archivist who supplied the title. On the other hand, there are the shots of the first flights of the Avro CF-105 Arrow, registration RL-201. The enthusiasm of the day and the pride in the captured images is clear in the following example: an image of Avro employees in a crowd watching the flight was taken by an unknown corporate photographer and given the title, “More massed Avro Employees - great!”

In the rush of work at A.V. Roe, the corporate photographers did not always have time to go back and give a negative a title or date. It’s up to us now to help fill in the context for the moments they captured on film. Take a look and let us know if you can help out!

![[Vending Machine] Photograph of a vending machine with its door open](/sites/default/files/styles/large_1/public/2019-03/hs-84681-s.jpg.webp?itok=ThPwle5O)

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)