Inside Ingenium’s smallest collections storage room

Tucked into a second-floor corner of the new Ingenium Centre in Ottawa is a collections storage room so small and inconspicuous that you might just miss it. Behind the mundane-looking door is a series of five shelving units with over 350 instruments, dials, and other historic artifacts housed in resealable plastic bags, looking for all the world like the bagged lunches of a post-apocalyptic robot. Can you guess why these artifacts are special — and why they are sealed in baggies in their own little room?

Your first clue: If you are a human — not a post-apocalyptic robot — and you spend too much time in this room, you might find it too “hot” to handle.

Your second clue: These artifacts emit a special type of energy.

Your third clue: These artifacts are sealed in plastic to contain a special type of hazardous dust. Humans who handle the artifacts outside their plastic enclosures protect themselves by wearing Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

So…did you guess?

These artifacts are radioactive, meaning they produce energy in the form of ionizing radiation: high-energy particles and atoms that can damage living cells at an atomic level. We have just finished packing and moving the radioactive artifacts from our old warehouses, into the new custom-built Ingenium Centre. You might guess that the move was not easy; it is very different from packing up your house! We had to plan for our safety, the safety of future visitors to the Ingenium Centre, and the safety of these sensitive historic artifacts.

Image gallery

Pandemic-style safety

Safety with radioactive collections is a lot like pandemic safety. We minimize our risk by following three rules:

- Physical distancing: The further you are from the radioactive artifact, the less radiation you are exposed to.

- Wear your mask (and other PPE): When handling a radioactive artifact, wear your PPE! We wear gloves, lab coats or suits, respirators, and eye protection. This PPE protects from inhaling or touching radioactive dust (as an added benefit, it protects us from COVID-19). We also have personal dosimeters which record our cumulative radiation exposure while working with radioactive artifacts.

- Minimize time: The less time you spend with the radioactive artifact, the less radiation you are exposed to.

And of course… we wash our hands.

Hot, or not?

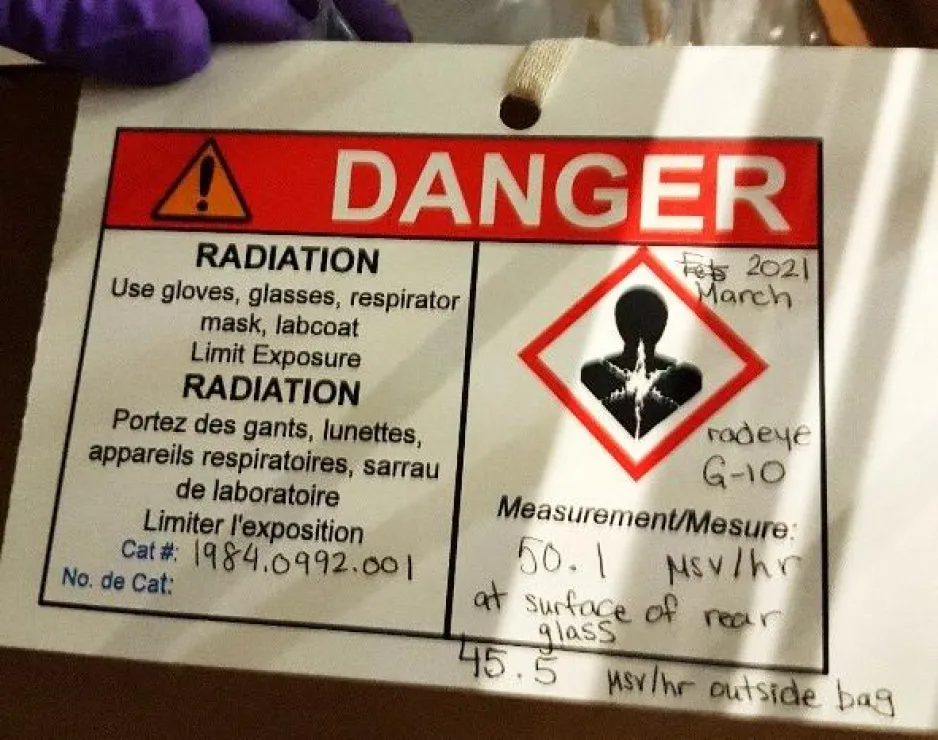

How do we know which artifacts are radioactive, or “hot”? Unfortunately, we cannot tell just by looking at them. At Ingenium, we have two instruments that measure different types of radiation: a Dosimeter 3007A, which measures alpha (α) and beta (β) radiation, and a RadEye G-10, which measures gamma (γ) radiation or gamma rays. Gamma rays are the most dangerous, and can even go through walls. Unfortunately — or fortunately — our conservators have not grown in size or acquired incredible strength after being hit by gamma rays. We will let you know if this changes.

The Dosimeter 3007A, used to measure alpha and beta radiation.

A RadEye G-10, used to measure gamma radiation.

Example of a radioactive hazard tag.

Since gamma (γ) rays are the most harmful type of radiation in our collections, we always check for gamma radiation first. If no gamma radiation is present, we then measure alpha and beta radiation. Radiation measurements are written on special hazard tags, which help staff and researchers see how hazardous a particular artifact is.

Hot off the shelf

A water jar and radium biscuit, used to make radioactive drinking water (Cat. No. 2002.0538).

What kinds of radioactive artifacts are in Ingenium’s collection? Some of Ingenium’s radioactive artifacts are kind of wacky. Like this jar with a radium biscuit, made circa 1920 in Toronto, Ontario by Radium Health Products of Canada. Using the jar and biscuit, you could make radioactive drinking water at home. Yes, drinking water. Water infused with radium was once thought to have curative properties. Luckily we now know that drinking radioactive water is a bad idea (do not try this at home!).

Another interesting radioactive artifact is this analytical balance, manufactured before 1935 and used by Dr. Marcel Pochon to weigh the first radium mined in Canada. Dr. Pochon was a student of the famous scientist who discovered radium… Dr. Marie Skłodowska-Curie, winner of the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics and 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. You may have heard of her.

Image gallery

Other examples of radioactive artifacts in Ingenium’s collection include thorium lenses (photographic lenses containing the element thorium (Th)), watches, a spectrophotofluorimeter (an instrument used to measure fluorescence of chemical compounds), medical implants, a smoke alarm, a missile, and a telephone translator. Larger radioactive artifacts that do not fit in the Radioactive Storage room are kept in other secluded areas.

But the vast majority of Ingenium’s radioactive collection consist of dials and instrument faces painted with radium paint. You may be familiar with radium paint from the Radium Girls book and movie. Used from the early 1900s until as late as the 1960s, radium paint glowed in the dark, which is useful in nighttime flying and driving. As the paint degrades, it produces radioactive dust, which is hazardous to inhale or ingest. To protect ourselves and future visitors, we packed artifacts with degrading radium paint in sealed polyethylene bags before moving them to the Ingenium Centre.

Image gallery

So... should I be worried?

No. Although we do have radioactive artifacts, it is completely safe to visit and work at the Ingenium Centre. The radioactive storage room is located far away from regular foot traffic, and is equipped with special sensors, a warning light, and ventilation. You could stand in the hallway outside the Radioactive Storage room for 1,000 hours straight before reaching the recommended Annual Public Dose Limit. When working directly with the artifacts, wearing the correct PPE protects you from any hazardous dust. Ingenium conservators also wore personal dosimeters while packing the radioactive collection, and the dosimeter readout showed negligible amounts of radioactivity over the weeks-long period.

Go further

Ingenium works closely with the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission to ensure our collections areas meet or exceed all federal regulations. For more information on ionizing radiation and its regulation in Canada, check out the resources available from the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission:

Introduction to radiation

Have more questions about the conservation of technological artifacts? Connect with the Ingenium conservation team on Twitter @SciTechPreserv

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)