Honeybees feel the sting of mystery toxic exposure

For the honeybee colony at the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum, life hasn’t exactly been sweet this fall.

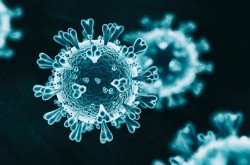

In mid-September, the colony suffered from acute poisoning – which typically happens when the bees visit flowers that have been recently sprayed with an insecticide. Sadly, the results were deadly.

“When our interpreter came in to the exhibition, three quarters of the bees were piled up at the bottom of the hive,” explains Nadine Dagenais Dessaint, an education, interpretation and exhibition officer with the Canada Agriculture and Food Museum. “Some were dead, others shaking or falling down and trying to climb up the frames – just to fall down again.”

The observation hive was taken outside, and the dead and dying bees were removed. Museum staff called a bee inspector from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, who visited the farm on September 17. The inspector took samples of the bees – dead and alive – to test for disease. The museum is waiting for the test results. Unfortunately, testing does not measure pesticide residues.

About 80 per cent of the honeybee colony – over 3,000 honeybees – were lost in the incident, says Dagenais Dessaint. Yet the cause of the poisoning remains a mystery to museum staff.

“We checked with the City [of Ottawa] and with Ornamental Gardens, but no one sprayed around the farm,” says Dagenais Dessaint. “As for Agriculture Canada, considering that most crops have already died off, it is very unlikely that they used any insecticides.”

Dagenais Dessaint keeps her own honeybee colony at home, and says she has experienced poisoning incidents in the past – but nothing like this.

“I had some poisoning at home – where the bee colonies are at least five times bigger than at the museum – and not nearly as many bees died,” says Dagenais Dessaint. “So whatever the musuem’s bees got themselves into, it was extremely poisonous to them.”

Dagenais Dessaint believes the massive die off had to be caused by either a pesticide or another product toxic to honeybees – that contaminated their food or water source.

The museum has about 1,000 honeybees left, and currently there are no plans to supplement the colony with more bees.

“I can’t add adult bees – bees from different colonies fight and the new bees could kill the queen,” Dagenais Dessaint explains. “To add bees to the observation hive, I need to add brood frames – frames with larvae and pupae – from other colonies.”

She adds that with queens laying fewer eggs at this time of year, brood frames are getting hard to find in regular colonies – and removing any would be detrimental to the bees surviving the winter.

The good news is that the bees are now on the road to recovery.

“As of now, they are doing much better,” says Dagenais Dessaint. “The queen is laying eggs again and behaving normally; the workers are foraging and collecting pollen and nectar.

“Hopefully, the queen in the observation hive will continue to lay a little longer – and the bee population will build up before winter. We need a good cluster of bees if the colony is to survive until spring.”