Behind the scenes of the Ingenium big move: Hazard mitigation of a print maker’s drawer

Moving a museum collection can be messy. Imagine all of the wonders your grandparent’s attic held when you were a child, and then picture it expanding to the size of a warehouse. Actually, several warehouses! That’s what Ingenium staff in Ottawa have been dealing with — as they carefully move the national science and technology collection into a new, state-of-the-art storage facility called the Ingenium Centre.

One of the great things about a museum collection move is it enables staff to assess artifacts and how they’re stored. A vast variety of objects — from trains to dental tools — have their condition assessed, hazards identified, and are then packed for moving and long-term storage.

Just like in your grandparent’s attic, along with all the treasures there were likely little dangers lurking in unlabelled boxes, waiting to be opened up. This is where Conservators come in. With a trained eye, hazards can be assessed, mitigated, or remediated when needed.

With the move, the general approach is to mitigate (lessen the hazard) and where that is not possible, remediate (remove the hazard). This is so the move can continue on schedule, and objects will still be safe to handle as part of the move — and for anyone accessing the collection in the future.

The print maker’s drawer, partially emptied. Note the mouse nest and deteriorating lead ink tubes.

A safe way forward – the process of assessing hazards.

While sorting through Ingenium’s proverbial attic, I came across a single drawer hiding behind a metal lathe. The drawer was brimming with little brown paper packages, and I had a feeling they were filled with lead foundry type. Based on previous packing experience and conversations with Sarah Jaworski — Ingenium’s Assistant Communications Curator — about lead type and “one-man job shops,” I knew I would likely find more hazards in the drawer. (For a dive into foundry type, check out Sarah’s article, “Inside the cigar box: A peek into a small, Canadian printing press.”)

At Ingenium, there are protocols to follow when dealing with specific hazards. Every collections staff member is given training on hazards, including where they hide in the collection and how to manage them. Each hazard has an information sheet we call “artifact hazard risk assessments and safe work practices” (RASPs). These RASPs allow for quick access to information about the hazard, how it is presented, and how to best manage it. They also contain a uniform labelling structure for hazards. These labels use the Globally Harmonized System pictograms, and are a quick and straightforward way of bringing someone’s attention to any hazards an artifact may have — indicating to use extra caution when handling the object.

With my RASPs in hand, and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) donned, I was ready to further investigate the drawer. After removing some of the lead type, I discovered that some of the print ink and compounds were in lead tubes, which were remarkably corroded. There was also evidence of a mouse nest in one of the corners of the drawer. With the hazards already compounding, I knew it was time to call in other conservators to help contain the hazards in the drawer.

Time for hazard mitigation!

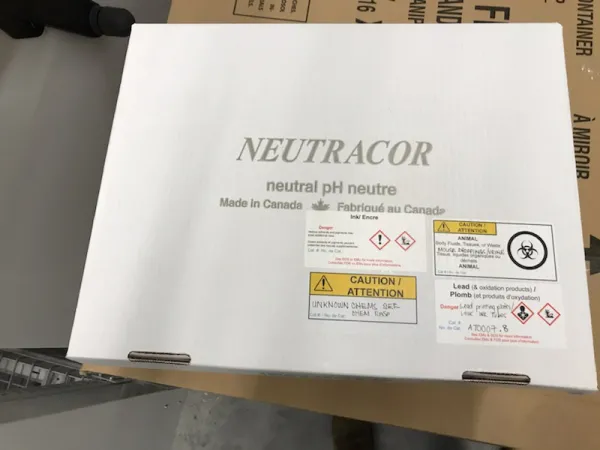

With the team assembled in protective Tyvek suits, P100 respirators, goggles and nitrile gloves, we set to work on decontaminating the drawer. We attacked the drawer in three stages – vacuuming, bagging, and tagging. Due to the amount of lead corrosion, everything removed from the drawer was lightly vacuumed with an Ultra Low Particulate Air (ULPA) filter. Because of the lead and animal biohazard contamination, everything that came out of the drawer was sealed in individual polyethylene bags, to contain the hazards. The bags were then labelled using the RASP system, and then put into acid-free Neutracor boxes for storage. The boxes were also labelled, so that anyone opening the box in the future will be aware of the hazards within.

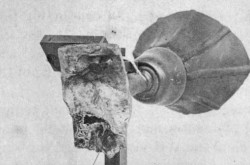

With our process well under way, we uncovered a few more delights in the drawer. Carpet beetles had been eating the natural glue used on paint brushes causing the bristles to fall out; rubber rollers that were used for print making had melted into the mouse nest; plastic handles on tools had shattered; and there were several unknown chemical compounds in the degraded lead tubes.

Image gallery

The mouse nest was sprayed with a 10% bleach in Reverse Osmosis water solution to disinfect it, and was then discarded. The drawer itself was wrapped with polyethylene sheeting to contain the remaining lead, animal biohazard, and unknown chemical contamination. Since wood is so porous, the contaminants migrate deep into the wood, and even with vacuuming and cleaning, can’t be considered safe to handle with bare hands or left uncovered on a shelf.

From containment to decontamination, this project took an afternoon to complete. While that may seem like a large amount of time to some, health and safety is always the most important part of the move. Conservators are the first line of defence when it comes to ensuring the safety of anyone accessing the collection.

Can objects be too hazardous? Definitely! While Ingenium is responsible for Canada’s most hazardous collection, part of our assessment includes determining how much is too much. It’s important to note that we don’t get rid of objects simply because they are too hazardous. For example, Ingenium has a large collection of radioactive objects (see “Inside Ingenium’s smallest collection storage room” for how we store our radioactive objects). The Conservation team works with the Curatorial staff to make recommendations if a hazardous object should be disposed of. Other factors are also considered in the decision, such as the condition of the object, the provenance, or if there are multiples of the object in the collection.

This project was so interesting because of the wide spread of hazards found within the drawer. It is a great example of the efficacy of the hazard mitigation protocol used at Ingenium. Through our RASP system of safe handling and labelling procedures this drawer of hazards is now safe to handle, and be stored safely in the new collections storage in the Ingenium Centre.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!