A forgotten fortieth: Remembering the SWINTER Aircrew Trial

A new oral history project at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum aims to preserve an important chapter in the equality rights of women in the air force.

The Servicewomen in Non-Traditional Environments and Roles (SWINTER) Aircrew Trial — one of four military trials held between 1979 and 1985 — represents an under-studied part of Canadian history. This is why interviews with women like Rosemary Park are so important. The museum’s SWINTER Aircrew Trial Oral History Project aims to preserve a varied collection of stories from those who lived through the trial, to ensure that these perspectives are not lost to the past.

A forgotten fortieth: Remembering the SWINTER Aircrew Trial

In 1972, Rosemary Park made a life-changing decision: She decided to join the Canadian Forces as the first female candidate for the Regular Officer Training Plan. She joined for patriotism — to fight for Canada. Yet, that was not an option for servicewomen at the time.

In 1972, Park was given only four military occupations to choose from: Personnel Administration, Air Traffic Control, Air Weapons Control, and Nurse. “None of these were interesting to me,” Park shared in a recent interview with the museum. “I had joined to fight and to defend Canada.”

Today, 49 years later, the opportunities for women in the (now) Canadian Armed Forces are limitless. Servicewomen have access to all military occupations — across all three environments — even the combat arms. However, servicewomen’s history shows us that these changes did not come easily.

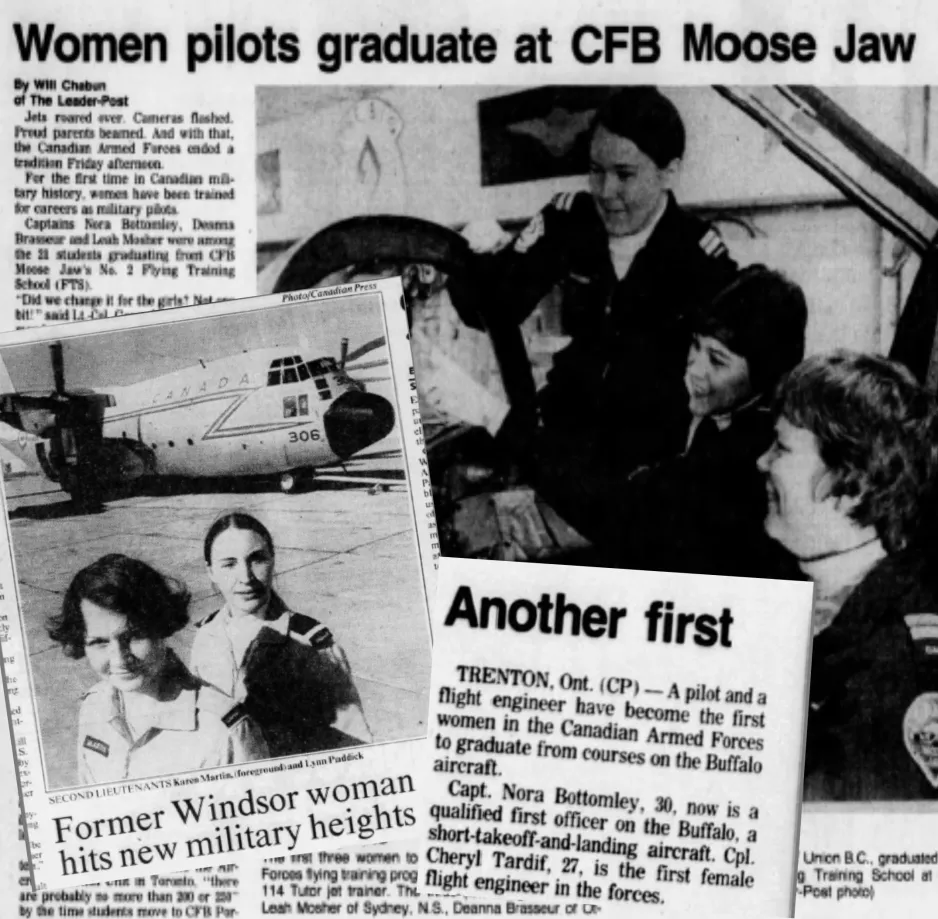

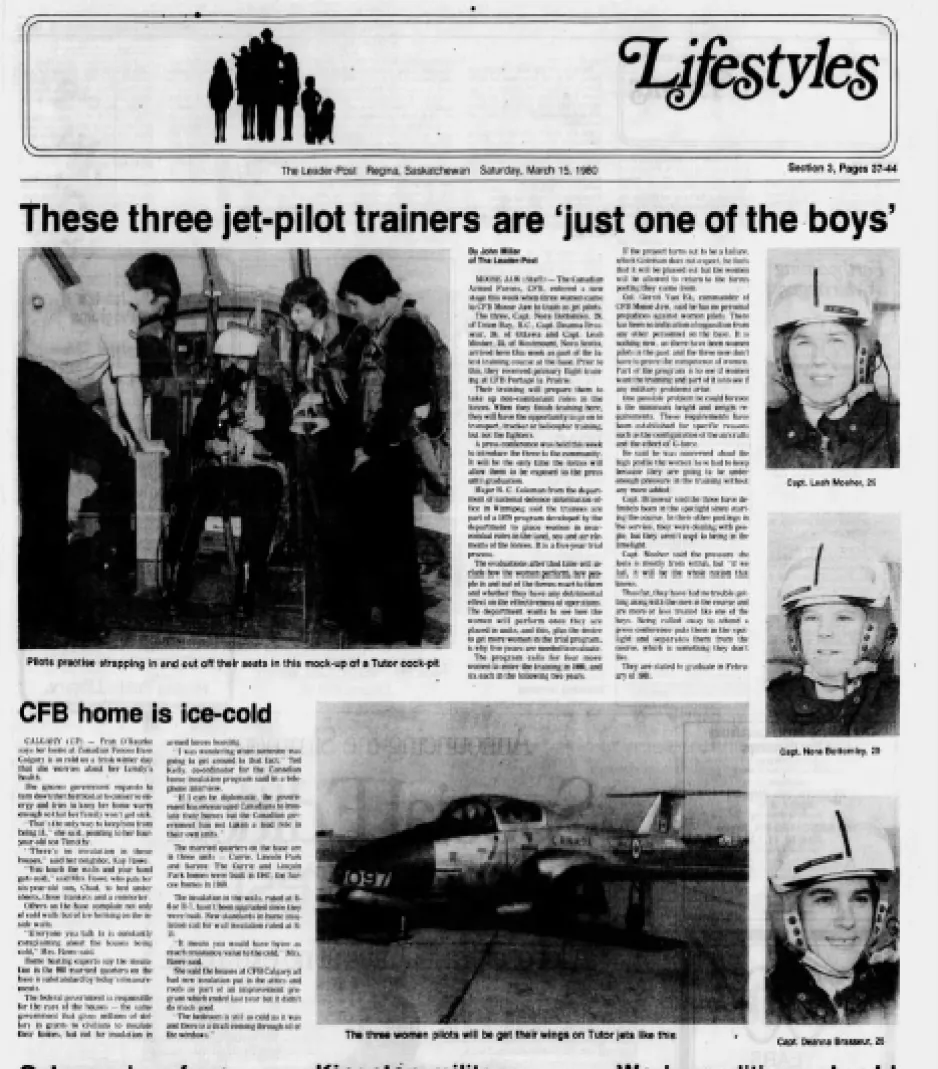

1981 was a year of many firsts for women in the Canadian air force. That year, servicewomen who had enrolled in the SWINTER Aircrew Trial earned their wings as pilots, air navigators, and flight engineers.

Captains Nora Bottomey, Deanna Brasseur, and Leah Mosher were the first servicewomen to complete primary flight training at CFB Portage La Prairie, Manitoba. In March 1980, they arrived at CFB Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan to train as jet pilots on the Tutor CT-114.

A critical performance evaluation

In fact, 2020 was the anniversary of a significant moment for women in the Canadian military. As part of the SWINTER Trials, 280 servicewomen served on a trial basis in nine near combat, previously all-male units between 1980 and 1985. Four separate trials were held during this period. In the Land Trial, women served in two field service units that supported land combat operations; in the Sea Trial, women served on a single non-combatant ship; in the Alert Trial, women were posted to an isolated communications station above the Arctic Circle; and in the Aircrew Trial women served as aircrew in five transport and mixed transport search-and-rescue squadrons.

The SWINTER Trials assessed the ability of women to perform in each role compared to men, the operational effectiveness of mixed-gender groups, the resource implication of integrating women into previously all-male units, and the sociological effects of women on unit cohesion, servicemen, and their families.

The trials were the military’s response to the Canadian Human Rights Act of 1978, which required the military to produce evidence that the exclusion of women from certain occupations and units was a “bona fide operational requirement.” Research reports written by the military’s Personnel Selection Branch during the trial period called the trials the most “ambitious study of the issue ever undertaken by a Western military.”

The photo gallery below depicts aircraft from the collection at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, which were similar to aircraft flown by servicewomen during the Aircrew Trial. The SWINTER Aircrew Trial Oral History Project is showing curators at the museum that aircraft in their collection could potentially be used to tell servicewomen’s stories.

Image gallery

Capturing a moment in Canadian history

The Canada Aviation and Space Museum is on a mission to better understand this moment in Canadian history, particularly the Aircrew Trial: the first time the Canadian air force allowed women to train and serve as pilots, air navigators, flight engineers, and traffic technicians (although no women were recruited as traffic technicians during the trial period).

As Canada’s national aviation museum, curatorial staff handle artifacts of military aviation all the time. In fact, over 60 per cent of the museum’s collection is military. While the museum strives to highlight the achievements of women in Canadian aviation in their exhibition space, there are currently no exhibitions focused on the history of women’s integration into the air force. This is why the museum is embarking on a new oral history project — in partnership with Servicewomen’s Salute Canada — to interview women who were involved in the Aircrew Trial.

A smiling Major Rosemary Park receives a Certificate of Military Achievement in 1983. At this time, Park was posted to the Canadian Forces Personnel Applied Research Unit, acting as the SWINTER Trials’ primary researcher.

Rosemary Park was a key figure in this history. In 1981, Park was assigned as the Regular Force Personnel Selection Officer to conduct research for all four of the SWINTER Trials. Not long before, Park had completed a Master’s thesis investigating the influence of masculine and feminine sex-role characteristics on career choices. She came to her position with new ideas about gender: gender roles were socially determined, and the binary was not useful. “My Master’s research primed me to see the SWINTER Trials as something where we could not stick to the old assumptions,” said Park.

Dismantling the “shelf theory”

It didn’t take long for Park to realize that senior military leadership had other ideas about the trials. “It was motivated to fail and to allow the military to continue unchanged.” The 1979 National Defence Headquarters Directive that launched the trials cast a “wide net” to find evidence that women’s employment should not be expanded. If women were found to perform their jobs well, then other factors were considered such as their impact on the unit socially, the opinions of military spouses, and even the opinions of the Canadian public.

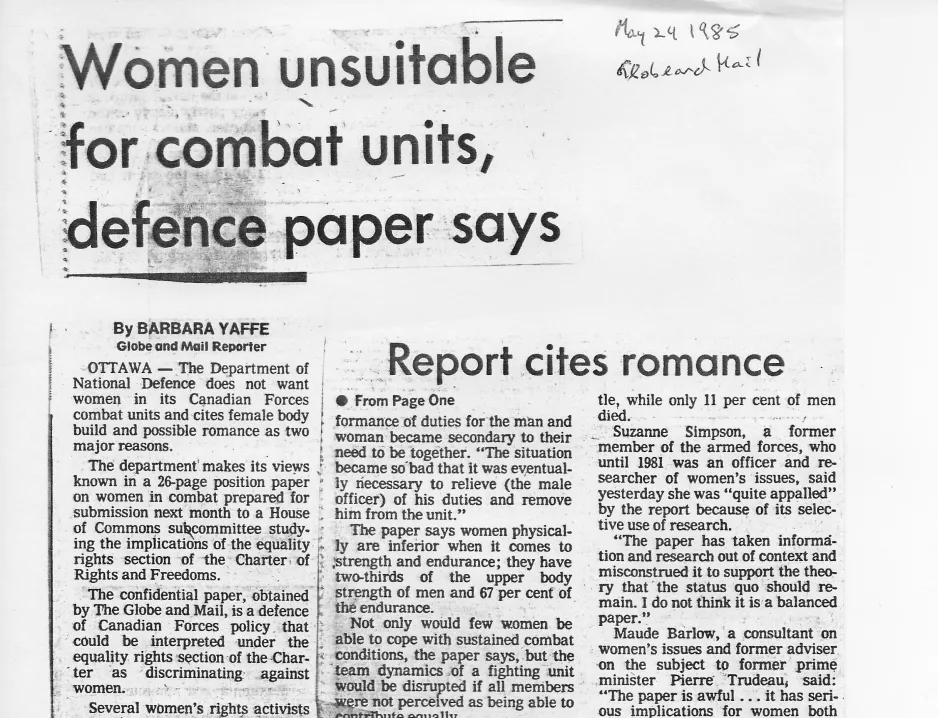

While the SWINTER Trials proved women were fully capable of working in non-traditional roles, resistance persisted. On May 24, 1985 the Globe and Mail leaked a Canadian Forces report that argued women were physically unsuitable for combat, and the military should be exempt from the Canadian Human Rights Act.

“The message was that military leadership didn’t want it to work,” recalled Park, “and it was almost inconceivable that women could or should do these jobs.”

These assumptions were the result of a long history in the Canadian military of using women as supplementary labour (the Second World War is a great example!). This is what Park called, “the shelf theory...When you needed women, you took them off the shelf. When you didn’t, you put them back on.” According to Park, “this is why SWINTER was so significant.”

The SWINTER Trials contributed to the end of the “shelf theory” mentality in the Canadian military. Despite assumptions to the contrary, the research produced by Park and her colleagues provided evidence that there were no “bone fide occupational requirements” for limiting the employment of servicewomen. In the Aircrew Trial, women were found fully capable as pilots, flight engineers, and air navigators. In addition, four out of the five trial squadrons achieved successful social integration.

Military leadership did not easily accept these results at first, but by 1986 the air force had officially opened the occupations of pilot, flight engineer, and air navigator to women. By 1987, the air force opened all occupations, allowing Captain Deanna Brasseur and Captain Jane Foster to earn their wings as the world’s first female fighter pilots in 1988. In 1989, the Canadian Armed Forces followed suit and opened all positions — including combat arms — to women. The research produced during the Aircrew Trial is considered a key factor informing these decisions.

“You see this resistance right up to the highest political level,” said Park, “until you can no longer argue your point. Until somebody says, ‘enough, we have to change.’”

Now retired from the military, Park is the chair of Servicewomen’s Salute Canada, who has partnered with the Canada Aviation and Space Museum for the SWINTER Aircrew Trial Oral History Project.

The SWINTER Aircrew Trial remains an under-studied topic in Canadian aviation history, yet the trial represents an important step for improving the equality rights of airwomen in Canada. As the museum moves forward with the new SWINTER Aircrew Trial Oral History Project — and captures the words and experiences of servicewomen such as Rosemary Park — we can ensure that this vital chapter of Canadian women’s history is not forgotten.

We may have forgotten the fortieth anniversary, but that does not mean we have to forget the fiftieth.

![A block of photographs showing some of the people involved in the bombing of beluga whales in the estuary and gulf of the St. Lawrence River. Anon., “La chasse aux marsouins [sic]. » Le Devoir, 15 August 1929, 6.](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_7/public/2024-09/Le%20Devoir%2015%20aout%201929%20page%206.jpg?h=584f1d27&itok=TppdLItg)