Hand-built bicycle tells a historical story of a colourful, Ontario teen

The Billings Estate National Historic Site is currently displaying a curious wooden bicycle. It was hand built in the late 1890s by a teenager named James Henry Blair, using materials scavenged off his father’s Gloucester farm. Artifacts at the Canada Science and Technology Museum give us a rare chance to explore the mindset of this young inventor as he puzzled through the process of how to build a bicycle with limited resources.

A day after James and his bicycle were spotted in downtown Ottawa, the Ottawa Citizen featured an article describing the event, published October 12, 1899.

On the October 11, 1899, James Henry Blair caused quite a stir when he rolled down Sparks Street on a peculiar wooden bicycle. So much so that the Ottawa Citizen published an article featuring the young inventor the next day:

“Something new and novel in bicycle construction was seen on the streets of the Capital yesterday. The machine was a home-made affair, built almost entirely of wood, giving it, if not a graceful, a decidedly substantial appearance. The designer, James H. Blair, a 17-year-old lad, had ridden in from Blackburn, a distance of about four miles, and he seemed to keenly enjoy the sensation his rustic mount created…”

The frame, handlebars, wheels, and saddle were carved out of ash wood, the pedals had been borrowed from an “old high-mount bicycle” and the chain and sprockets were harvested from a retired binder, all scavenged from his father’s Gloucester farm. When asked why he built the bicycle he answered: “for amusement alone.”

James posing in South African War regalia. The exact date is unknown, but this photo was likely taken in 1901 or 1902.

The bicycle is now an artifact in the City of Ottawa Museum’s Collection and is currently on display at the Billings Estate National Historic Site, where it is used to introduce visitors to James’ colourful life. James was born in 1881 to Hugh Blair and Jean Greer. He grew up as one of 11 children on his father’s farm on Innes Road, the present-day location of Ritchie’s Feed and Seed. As a youth, he was known for his skills in art and woodworking. Prior to building his bicycle, he had won a Montreal Witness contest for both a pig he moulded from clay and the wooden box he carved to mail it in.

As an adult, he served in the South African War, worked with Thomas Edison for the American Talking Picture Company, and eventually settled in Staten Island, New York, where he invented dental equipment for the Chayes Dental Instrument Company.

Today, the novelty of this bicycle lies in the fact that James built it himself using limited resources. But how did he manage it? How did he figure out that the chain and sprockets from a binder would work for a bicycle as well?

What is a binder anyway?

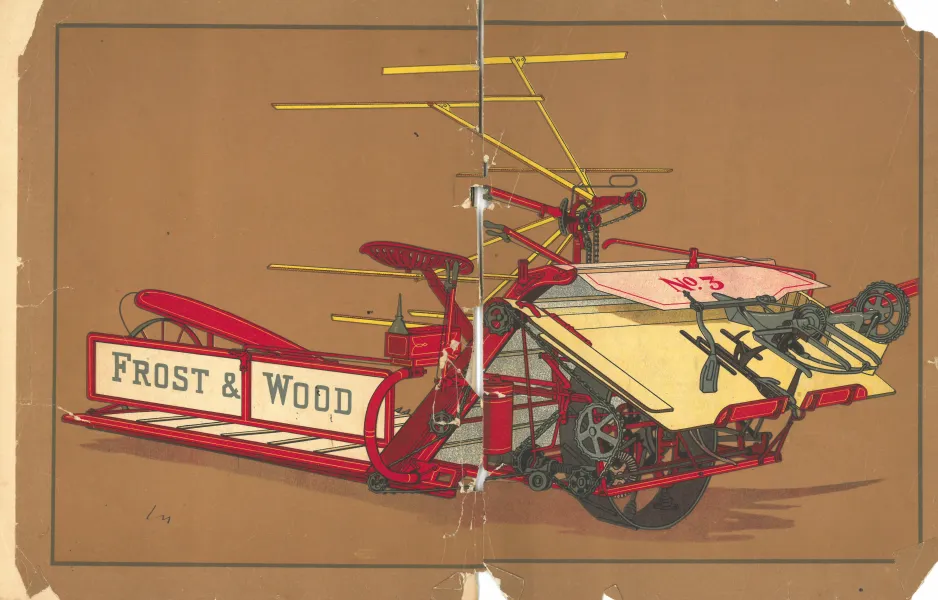

A cover page from the 1904 Frost & Wood catalogue, advertising their No. 3. Binder. Canada Science and Technology Museum trade literature (AGR F9390 3037 L25241).

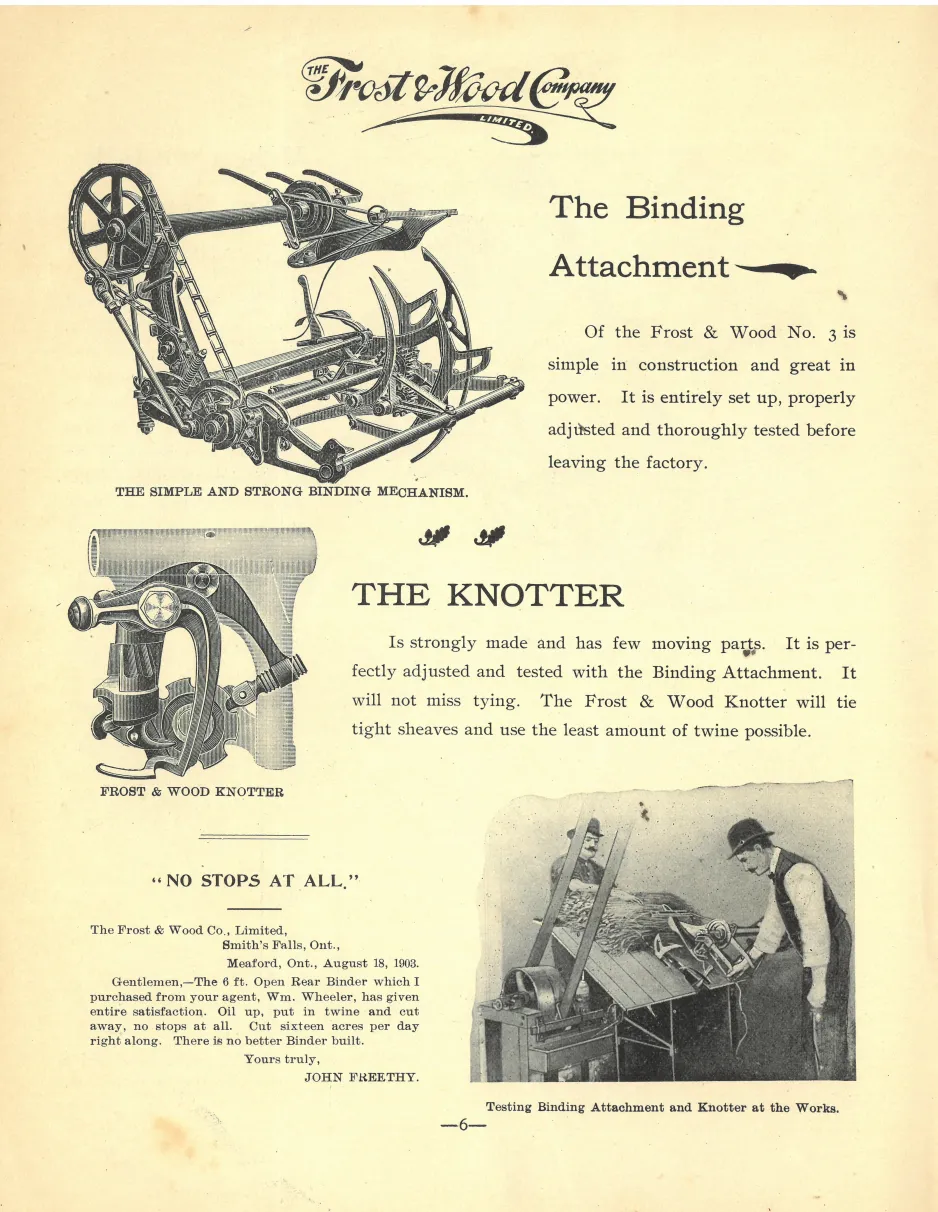

A page from the Frost & Wood 1904 catalogue describing the binding attachment and knotter on the No. 3 Binder. The binding attachment looks familiar, doesn’t it? Canada Science and Technology Museum trade literature (AGR F9390 3037 L25241).

A binder is a type of harvesting equipment that mechanically cuts and binds wheat, and other stalks of grain, into a bundle. The device that binds the wheat with twine, called the “knotter,” was patented by Englishman F.B Appleby in 1874. By the 1890s, Ontario manufacturing companies like Massey, Harris and Frost & Wood were producing binders with this mechanism.

The binder was an extremely important piece of technology for farmers in the nineteenth century as it fully automated the processes of cutting, gathering and bundling wheat.

In their company history, Massey-Harris boasted that the binder harvested grain at “6 to 10 times the speed” of manual methods with “a trifling fraction of the expenditure of human energy.” Binders were used by farmers all across Canada in the late nineteenth century; in Gloucester, some of the first binders were the Harris “Brantford” binders and those produced by Frost & Wood.

At the Science and Technology Museum we have a few nineteenth century binders, such as this machine from the 1890s (1971.0299.001). It doesn’t take a close inspection to notice that parts of the machine do, in fact, resemble a bicycle.

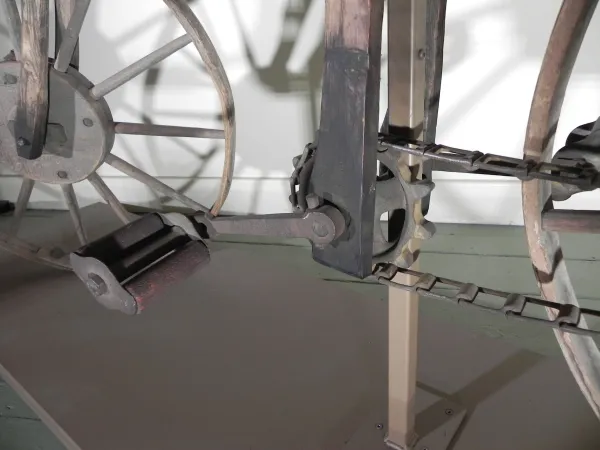

This is a Massey-Harris no.4 binder that was in use between 1890 and 1900. While it may not have been the exact binder James would have had on his farm, the technology would have been similar if not the same. Note how the binding attachment on the right side is driven using a chain and sprockets. How does it compare to the chain and sprockets on James’ bicycle? Canada Science and Technology Museum (1971.0299.001).

On the left is the front sprocket and chain on James’ bicycle and on the right is a sprocket on the Massey-Harris No. 4 binder attachment.

On one side of the binder is the binder attachment where the knotting mechanism is located. It is driven by a chain and a series of gears – very similar to a bicycle’s drive train! On the farm, James would have observed these technologies being used and likely watched or helped his father repair a binder over the years. On trips into Ottawa, it is likely that James would have also observed bicycles of various designs, as the 1880s and 1890s were a period of rapid growth and innovation in bicycle technology. It’s not a stretch to assume the curious lad paid attention to how these new vehicles worked. For someone wanting to build a bicycle with no access to bicycle components, the binder was an obvious choice – but only to someone who had observed both technologies and understood their mechanics.

A binder being used on the farm of George Blair, James’ brother, in the 1950s. The farm was located next to the family farm on Innes Road, Gloucester. While James would have observed a horse pulling the binder rather than a tractor, this would have been a common scene throughout his childhood.

As an artifact, James’ bicycle teaches us many things. It demonstrates that the bicycle is a simple, accessible and versatile technology. Using only scavenged materials, and the mechanical and woodworking skills he learned on the farm, James built a functioning bicycle. With rough wheels and no brakes it may not have been the most comfortable ride, but it worked! At the same time, it teaches us that innovation and invention are processes of observation. James did not need to be a genius to build a bicycle. He only needed to observe the technological landscape around him, exercise his creativity, and make connections.

Interested in finding out more? Check out my sources for further reading...

“A Wooden Bicycle: A Country Lad With Brains Displays a Curious Wheel on City Streets.” Ottawa Citizen, 12 October 1899. Page 2. Accessed via Newspaper.com.

Blair, James Henry. Wooden Bicycle. 1898. City of Ottawa Museums Collection, Gloucester Museum, accession MG1984.0050.001.

City of Ottawa Museums. “Creative Hands At Work.” Exhibit display at the Billings Estate National Historic Site, accessed 7 June 2019.

Farnworth, John. The Advertising of Massey-Harris, Ferguson and Massey Ferguson. Ipswich: Farming Press, 1999.

Gloucester Historical Society. Blair Family File.

Gloucester Historical Society. “James Henry Blair, 1881-1955, Recreating an Inventor,” pamphlet. Ottawa: City of Gloucester, 1999.

Massey-Harris Company. Massey-Harris: 100 years of progress in farm implements: 1847-1947. SI: Sampson-Matthews, 1947. CSTM Collection, HD 9486 C22 M37.

Serre, Robert. “Pioneer Families of Glen Ogilvie.” Ottawa: Gloucester Historical Society, 2005.

Spence, A.J. and J.B. Passmore. Handbook of the collection illustrating agricultural implements &machinery: a brief survey of the machines and implements which are available to the former with notes on their development. London: His Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1930.

Walker, Harry and Oliver Walker. Carleton Saga. Ottawa: The Rudge Press, 1968.