Citizen science: Observing meteor showers

Watching a "shooting star" unexpectedly dart across a starry sky is awe inspiring. People will often ask, "What was that?" or "Where did it come from?" Beyond the inevitable "ooohs" and "ahhhs," there is an entire astronomical field devoted to their study. Meteor science is also one of the few remaining fields where amateur astronomers, equipped with only their eyes, can still contribute valuable data to the scientific community.

I vividly remember spending a part of my childhood in my backyard well after dark, looking for “shooting stars” and pondering at the beauty of the night sky. Astronomy has been a long-time passion of mine, and I still enjoy looking up every chance I get in the hopes of seeing something special.

Stargazing is a great way to connect with nature and to get away from the noise and distractions of the city. A pristine night sky is like a giant artist's canvas — full of intricate patterns, clusters of stars, glowing star clouds, and the Milky Way arching overhead.

Nature’s fireworks

I am especially fascinated with meteor showers. They are nature’s way of producing fireworks, and they require the simplest of technique to enjoy at their best — a lounge chair, a sleeping bag, and a pair of eyes to look up! An open sky in a rural area, away from sources of light pollution, definitely improves the experience. At certain times of the year, the Earth encounters “clumps" of dust particles. This gives rise to meteor showers such as the August Perseids and December Geminids, when more numerous streaks of light can be seen in a clear sky. These celestial events are rewarding and can be enjoyed by people of all ages. I love watching them, but I also take detailed notes about what I see and then I submit them to various organizations. This is a form of “citizen science” — the data can be very valuable for scientific analysis by researchers.

Comets and asteroids produce countless dust trails throughout the Solar System, and the Earth encounters several of them during the year. The quantity, movement, path, and brightness of meteors in the night sky can help astronomers “map” out the various dust streams, associate them with a certain parent object, and possibly even provide hints on the whereabouts of yet-to-be-discovered potentially hazardous Near Earth Objects (NEOs). Meteor dynamicists also use the data to help refine meteor shower predictions. Occasionally, meteor showers can be spectacular and might pose a threat to Earth-orbiting satellites. Refining predictions of the dates and times that Earth is due to cross dense dust concentrations allow satellite operators enough time to take preventive measures. A bonus for meteor observers is knowing when and where in the sky to look for these beautiful displays! Meteor science can, of course, provide valuable information about comets, which are some of the oldest bodies in our Solar System.

Geminids meteor shower

On December 12-13, 2018, I ventured out to see the Geminids meteor shower, one of the year’s best! It was a frigid night with a forecast low of -26 C, but that wasn’t about to stop me. A friend, Raymond Dubois, joined me for a road trip that took us about 100 km north of Ottawa. Our goal was to reach an area where the prospects for good sky transparency was best. Before long, we found a boat ramp overlooking a small lake with an outstanding view of the sky! Overhead, the winter stars and Milky Way were beautiful and the Geminids were active, with meteors going by left and right!

Geminids in the winter sky, above Lake Morisette: Composite image of 21 Geminids captured on the night of December 12-13, 2018. Blue Sea region, Quebec. Canon 6D, ISO 1600, Rokinon 24mm f/1.4 (set at f/2.0). Some cirrus and sky fog created slight halo effects around the brighter stars.

I prepared my sky tracking mount with two digital SLR cameras (one equipped with a wide-angle lens and the other with a telephoto lens). Then I went into my lawn chair and winter sleeping bag to look up and enjoy the night sky. Below me, I heard a multitude of cracks and pops caused by the ice from the frozen lake settling to the frigid temperature. I pulled out my 9x63 mm binoculars to take a peek at Comet 46P/Wirtanen, which happened to be near its best visibility. It was easy to locate the small greenish "fuzz ball” and I noted its motion against the stars over the course of the night.

Geminid meteors meet Comet 46P/Wirtanen: Composite image of six Geminids. December 12-13, 2018. Blue Sea, Quebec. Canon 5D, ISO 1600, Canon 70-200 f/4.0 (set at 135mm).

I kicked off my meteor watch shortly after midnight and continued until dawn. I took a few breaks during the night to stretch my legs, grab a snack, or attend my cameras. The cameras were running automatically with a remote-controlled timer, but I would occasionally change the field of view to frame a different part of the sky.

Geminid and the Beehive open star cluster: December 12-13, 2018. Blue Sea, Quebec. Canon 5D, ISO 1600, Canon 70-200 f/4.0 (set at 135mm).

I counted 256 meteors — a terrific night! The majority were Geminids but I also noted a number of meteors belonging to other active meteor showers, as well as those that aren’t associated with any known showers (known as sporadic meteors). I took voice notes and called out the time for every meteor. Occasionally, several minutes would go by without any meteor, followed by a quick flurry. The dark sky, away from the lights, allowed me to see many of the fainter meteors that would have been lost in the city lights. The most impressive meteor was brighter than any of the visible stars, and it left a sort of ghostly afterglow that lasted a few seconds. Brighter Geminids were typically white, slightly bluish, or yellowish. It was a night that I won’t soon forget.

Geminid below the Great Orion Nebula: December 12-13, 2018. Blue Sea, Quebec. Canon 5D, ISO 1600, Canon 70-200 f/4.0 (set at 135mm).

Comet 46P/Wirtanen near dawn: December 12-13, 2018. Blue Sea, Quebec. Canon 5D, ISO 1600, Canon 70-200 f/4.0 (set at 135mm).

Quadrantids meteor shower

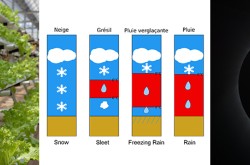

On January 3, 2019, I was planning to try my luck with the Quadrantids, the year’s first meteor shower! This meteor shower is not so well known, yet it is often rates as one of the top three of the year. The weather odds were against me this time, with snow squalls making this shower a near-hopeless case. The radar image, however, showed a possible clearing south-west of Ottawa, past Kaladar. I took a chance and drove out in the middle of the night, braving treacherous snow-covered roads and ice. It was slow going for most of the way, and I questioned if I was doing this all in vain. Thankfully, the roads were in better shape as I passed Perth along Highway 7 and it stopped snowing. Eventually, I arrived at the Lennox & Addington Dark Sky Site on County Road 41 at 4:30 a.m. It was a relief to see the stars; the clouds were receding away. Almost right away, I saw some nice Quadrantid meteors! The sky continued to improve. It was a very mild night, with the temperature hovering around 0 C.

The sky completely cleared shortly before 5 a.m. and I "signed on" for a formal meteor watch. It was a beautiful, pristine sky and the Quadrantids were active with bright meteors, occasionally coloured blue-white or yellowish. The total count in two hours was quite a tally with 55 meteors (41 Quadrantids, 4 Coma Berenicids, 3 January Leonids, 2 December Leo Minorids, and 5 Sporadics). The Earth’s orbital motion was clearly moving out of the Quadrantids dust stream, as the activity was tapering off at the end of the night. The highlight was an intense blue-green meteor that lit up the landscape like a lightning bolt; an amazing sight!

Serendipity was with me during these two observing sessions. I was among few people in eastern North America to have seen these meteors, due to overall poor weather. My results were submitted to the International Meteor Organization as part of their global analysis; my findings were integrated into a pool of data gathered from observers worldwide.

Sometimes, taking a chance with the weather can really pay off with an experience that is unforgettable and rewarding. So the next time there’s a good meteor shower, why not give it a try yourself?

International Astronomy Day: Saturday, May 11, 2019

Every year, astronomy enthusiasts, groups and professionals gather to share their passion of the night sky with the public. The Ottawa Valley Astronomy and Observers Group (OAOG), of which I am a member, will be celebrating this day with a free family-oriented outdoor event at SilverCity Chapters (2401 City Park Dr. in Ottawa). Weather permitting, the activities begin at 10 a.m. with solar observing (using specially equipped telescopes for safe viewing), displays and informative handouts. After sunset, there will be viewing and imaging of the Moon and other interesting sights through a variety of different telescopes! I will be present on site and I would be happy to answer any questions you may have about meteor showers. For information and updates, please visit us on Facebook.