Teen could bring clean water to millions

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

Rachel Brouwer is featured in Innovation150’s national public awareness campaign. Learn more.

Rachel Brouwer isn’t old enough to drive, but she’s got her own billboard, her own Wikipedia page, and an asteroid named after her.

The asteroid dedication – in addition to a $1,500 prize – was for coming in second at the 2016 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair after winning a gold medal at the 2015 Canada-Wide Science Fair.

It’s all because of an invention of Brouwer’s that could provide access to clean water in the developing world using some things she had in her kitchen.

A 14-year-old Canadian innovator

“Honestly it’s been so surprising,” says Brouwer, now a modest 14 year-old pioneer, who somehow finds time to also cook, manage a line of skin-care products, play basketball, soccer, and perform in her school band. “I wanted to come first in my class and it just kind of exploded from there.”

The invention, which the Bedford, Nova Scotia native came up with when she was just 13, is a no-fuel-needed, solar-powered process for killing potentially deadly bacteria in water, using 2 litre pop bottles, plumbing materials commonly available in developing nations, and a 3D printed wax indicator that costs just pennies.

The invention has literally grown up with Brouwer and vice-versa. She was a child of 11 when she first started on the idea, which came to her when she and her family visited rivers and lakes in New Hampshire that had ‘Contaminated. Do not drink’ signs posted at the water’s edge.

Growing up with her invention

At the same time, Brouwer was reading the book “I Am Malala” in which teenage Nobel Prize winner Malala Yousafzai recounts her life-risking activism and the harrowing conditions in Northern Pakistan. In addition to the violent regime of the Taliban, massive flooding in the region in 2010 caused a cholera outbreak that killed thousands and displaced millions.

It was the first time, Brouwer had heard of water making people sick. When she realized contaminated water could lead to far more than some signs in her family vacation destination, she decided she wanted to try to do something to help people in countries like Pakistan.

“When I was 11, I didn’t even know water security was a thing,” she says. “Once I had that realization; That not everyone was as privileged as I was, I started to think of ways I could bring those privileges to everyone in the world in need.”

As a teenager, Brouwer her idea and created a system that can both remove large particles (that contaminants can cling to even after pasteurization) and pasteurize the water, sterilizing it for safe consumption:

- Using a hand-pump, water enters a basic carbon and charcoal filter into the pop bottles.

- The bottles then have the indicators placed on them and the whole assembly is placed on a tin roof to heat up.

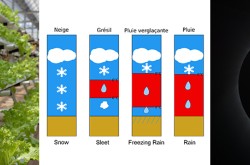

- The indicator, made of a special type of wax that turns colour when heated, changes from dark blue to light pink, indicating the water is heating up.

- When the water reaches 60 C (the temperature at which water is free from all harmful bacteria) the pink wax melts, letting users know the water is safe to drink.

Trial-and-error and then some…

“When I tested it, I realized it was hard to see when the wax melted or would harden, so I started thinking of ways I could change this,” says Brouwer. Eventually, she found a colour-changing powder used in cups that reveal a particular design with hot liquid in them and decided to mix this in to her a wax indicator.

“In some of the early versions, there were problems with surface tension where the wax would melt but not run into second vial, or where the colour change wasn’t enough. I designed and ordered over 30 indicators until I found the right one.”

The system has since been tested in the Caribbean and the Middle East, with plans to implement it on a larger scale through educators who are taking copies of the original device out in the field while Brouwer finishes her studies in Nova Scotia.

In the future, she’s interested in seeing the device help as many people as possible but she’s already set her sights on her next cause.

“I recently went to a conference where a room of educators talked about curiosity,” she says. “I got most of my sense of curiosity from my parents but I’m interested in fueling curiosity and creativity in the classroom so the next generation could have that more in school.”