Young students bring forgotten stories of the Spanish flu back to life

Through her school’s award-winning history project on the Spanish Flu pandemic, 11-year-old Tyya Strutt learned a somber truth.

“Most people who die in times of terrible events or peril are never remembered, especially if they are children,” says Strutt. “But this is not right."

Strutt and her Grade 5/6 class, at Dundas Central Elementary School in Dundas, Ontario, researched the story of Hazel Layden, a 15-year-old who passed away from the Spanish Flu in 1918. The students were drawn in by Layden’s story since she was a student at their school (a heritage building built in 1857).

“It was very impactful when we learned that Hazel went to our school, and she even learned in our classroom,” reflects Strutt. “She sat in the same room where we have our classes, and she played on the same playground as us. Hazel’s story meant a lot to us, probably because she was one of us.”

~ Tyya Strutt

The class — led by teacher Rob Bell — won an award for the Recovering Canada contest, a nation-wide competition run in 2018-2019 that challenged Canadians to share forgotten stories of the Spanish Flu pandemic. The contest culminated in an awards ceremony that took place at the Canada Science and Technology Museum on May 11, 2019.

“When we heard that we had won the award, our initial response were feelings of surprise, pride, happiness and excitement,” says Strutt.

Taking centre stage at the ceremony, Strutt and Bell shared the class’s approach to their online project about Hazel Layden, “The 1918 Flu Pandemic: Changing the Future Through History – the Defining Moments.”

The national contest was organized by Defining Moments Canada, an online community providing digital research and storytelling tools in commemoration of the centenary of the Spanish Flu epidemic. A catastrophic event, the Spanish Flu affected millions; yet the stories of Canadians implicated have gone largely untold.

A deadly and largely forgotten enemy

To put the impact of the Spanish Flu pandemic into perspective, consider the First World War—which was one of the deadliest conflicts in global history. It claimed the lives of over nine million combatants and over seven million civilians as a direct result of the war. The end of this conflict on November 11, 1918, and the sacrifice made by those in the line of duty is remembered and celebrated annually all around the globe. And yet, 1918-1919 was haunted by an even more deadly — and largely forgotten — enemy: The Spanish Flu. In just 18 months, more than one third of the world’s population was infected and 50 to 100 million people died; this is more than the Black Death, and more than the First and Second World Wars combined.

For the centennial commemoration, Defining Moments Canada has led an exploration of these stories using digital media. Here are a few more of the remarkable stories of Canadians who had their lives forever altered by the Spanish Flu pandemic.

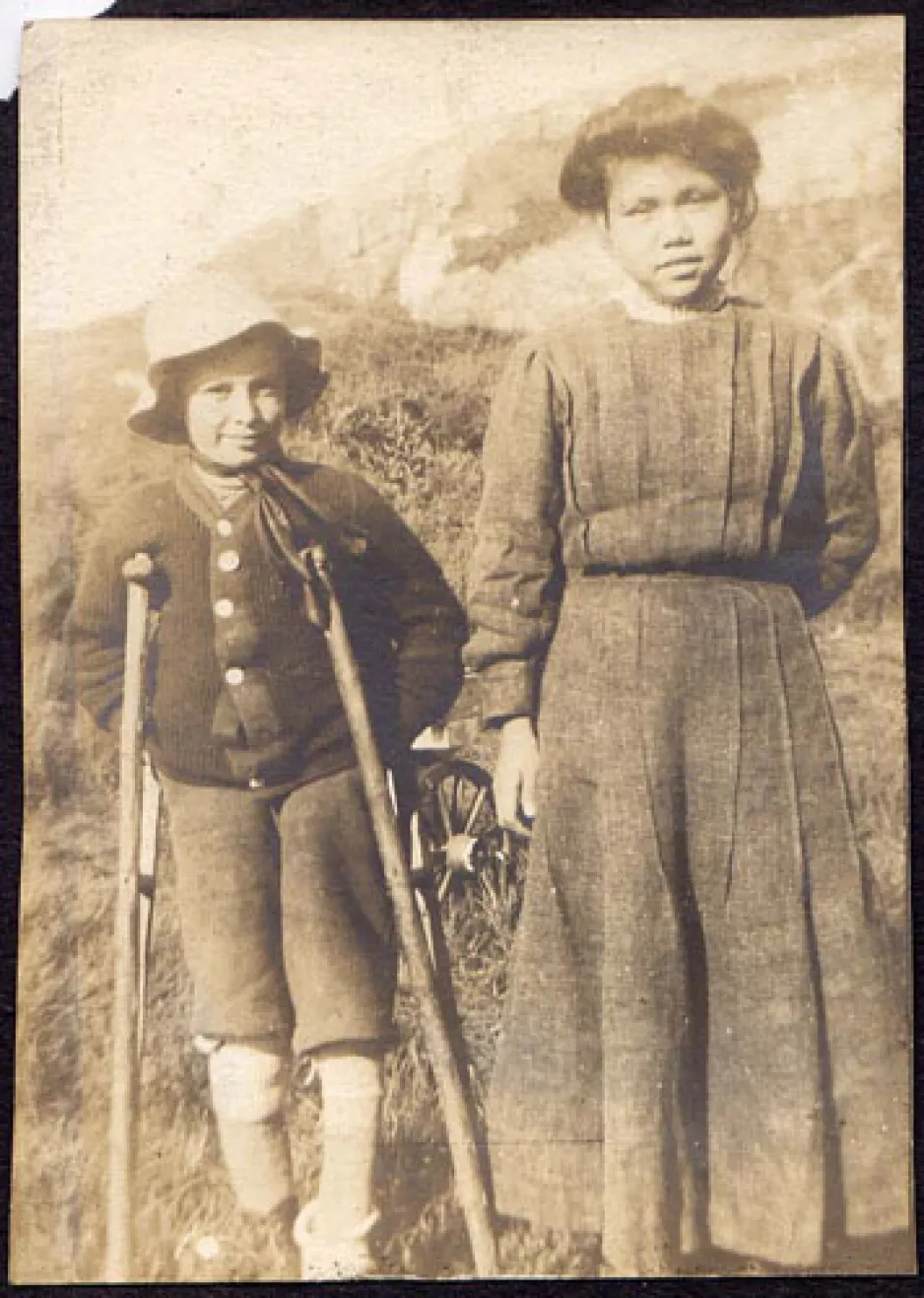

Lieutenant Blanche Lavallée departing for the First World War in 1915

Blanche-Olive Lavallée and the origins of the Spanish Flu

Blanche-Olive Lavallée was a French-Canadian nurse from Montréal who enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force to serve in Europe. She was recruited to a hospital outside of Paris, France in May 1915. Blanche-Olive was in charge of an operating room in what became one of the busiest Canadian Hospitals due to its proximity to combat zones. Her hours would have been filled with an endless flow of wounded, and her sleep would have been constantly interrupted by the sounds of artillery fire. By 1917, the physical toll from exhaustion and stress was so great that Blanche-Olive was routinely suffering from chronic appendicitis, anemia, and general weakness.

To make matters worse, in the spring of 1918 nurses and doctors started to see a severe and particularly virulent virus spreading rapidly around cramped military barracks. Already weakened from years of arduous conditions, Blanche-Olive was hospitalized with pneumonia, bronchitis, influenza, and acute appendicitis, and was sent back to Canada. She, and many other nurses and soldiers, unknowingly carried the Spanish Flu pandemic back to Canada.

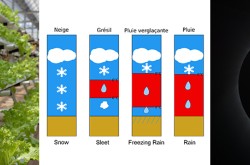

Amelia Earhart and the Spanish Flu in Canada

The first serious cases in Canada were reported in late summer 1918, in port cities like Halifax and Québec where ships were returning from war zones carrying the wounded and ill. Despite efforts to quarantine the sick, the disease spread like wildfire. Initially, patients had the usual flu-like symptoms: headaches, fatigue, fevers, aches, and sore throats. But as the disease developed, body fluid could build up, hindering circulation and filling the lungs. Ultimately, most deaths were caused by pneumonia, a secondary infection within the lungs.

In Toronto, the pandemic hit in September 1918. The hospitals filled quickly. Antiviral drugs did not exist, and within the close confines of the hospitals, many caregivers fell ill. One of these nurses was Amelia Earhart, of aviation fame, who was working at the Spadina Military Hospital on the University of Toronto campus. She survived the flu, but developed a severe sinus infection that required surgery and an entire year to convalesce.

Kirkina (right) and Ben Cumby, at Indian Harbour, 1909.

Elizabeth “Kirkina” Jefferies Mucko and the impact on public health

Across the country, all ages, all classes, and all communities were susceptible. Entire families fell ill. Elizabeth “Kirkina” Jefferies Mucko was an Inuit woman from Labrador. Together with her husband Adam Mucko, she raised seven children in the Sandwich Bay area on the Labrador coast. This community was particularly hard-hit by the pandemic, losing 20 percent of the population to the flu. Elizabeth’s entire family fell ill, and tragically, her husband and six of their children died. Since the family was quite isolated, Elizabeth had to bury her family herself.

With no antibiotics (they hadn’t been invented yet), physicians and public health officials had limited treatment tools. Instead, they relied on promoting preventative measures among the public. These included: closing public spaces like schools and theatres, ensuring proper ventilation in buildings, covering your mouth when coughing, quarantine measures, and wearing masks. However, in light of the magnitude, public health officials were criticized for using outdated and inadequate measures. This lead to the formation of the federal Department of Health in 1919.

Honouring memories

By comparison to the First World War, the painful history of the Spanish Flu in Canada has been all but forgotten. In commemoration, Defining Moments Canada gathered some of the forgotten stories of individuals, specific groups, and certain communities to document their unique experiences, and honor their memory.

The students of Dundas Central Public School never managed to find a picture of Hazel Layden; no school photo was taken that year due to the Spanish Flu epidemic. Her memory might have faded into obscurity, along with tens of thousands of others who succumbed to the epidemic. Instead, through the work of these young students, Hazel’s legacy will live on.

“She was one of us,” says Strutt. “She went to our school and lived in our neighborhood, and she was an important part of our community’s history. She was forgotten and this was not right. There was something exciting and empowering about being able to discover Hazel’s story after people had forgotten and to tell our community about her.”

For more information and to learn about other award winners, visit the Defining Moments Canada website.

Men wearing masks during the Spanish flu epidemic.