Curating sound culture: Exploring the history of the stethoscope

Few things say ‘doctor’ more than a stethoscope. Even in the modern medical field, which can be regarded as highly vision-based (imaging, scanning, observing), the stethoscope remains a powerful medical tool and an iconic symbol of past traditions. Above all, the stethoscope represents a deep and enduring relationship between medical practice and sound.

During my time as a practicum student for Ingenium, I worked on developing a research profile of the museum’s stethoscope collection, focusing specifically on a group of artifacts featured in the Medical Sensations exhibition at the Canada Science and Technology Museum. The goal of the research profile was to summarize and showcase information about each artifact, ranging from technical and biographical information to capturing the significance of artifacts in relation to their contributions to science, technology, and Canadian history at large. When looking at the stethoscopes in the museum’s collection, it became clear that there are many fascinating stories these artifacts can tell – stories about changes in technology, materials, designers, and users. The three themes I chose to focus on for my profile were technological innovation, materiality, and sociocultural context.

One of the earliest stethoscope models in the collection is a wooden replica of an original monaural stethoscope invented by René Laennec in 1816 (Image 1). This artifact was made in 1929, when monaural (single-ear) stethoscopes had already been phased out and binaural (two-ear) stethoscopes had become the standard. This replica was commissioned by Montreal cardiologist Dr. Harold Segall in 1929, based on a model owned by the renowned Canadian physician William Osler that traced back to Laennec in 1825. This stethoscope not only showcases an important early use of sound technology in medicine, but it also has an interesting cultural context: it was created when x-rays and imaging were becoming dominant in medical practice, thus evoking a sense of nostalgia for acoustic medicine.

Image 1. Replica of an early Laennec monaural stethoscope (artifact no. 2002.0473). This replica was produced in 1929. It was made for Dr. Harold N. Segall, a founding member of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CSS), and based on a model owned by William Osler, the renowned Canadian physician.

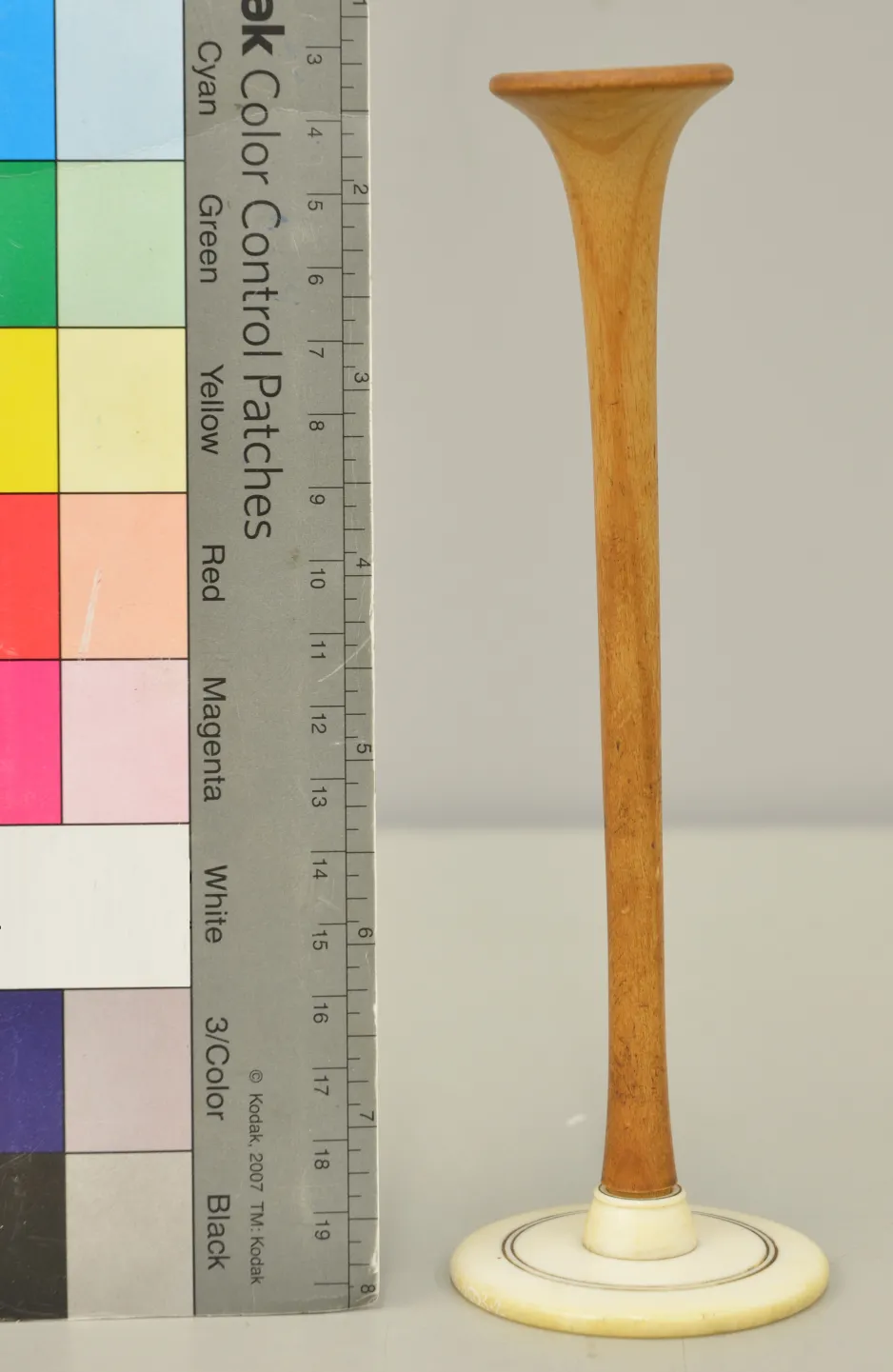

The Laennec design of a compact, sleek, wooden tube inspires ideas about innovative design in terms of practicality as well as acoustic qualities, especially in comparison to other monaural stethoscopes that emerged in the mid to late 19th century. Such stethoscopes had a concave bell shape on one end, to be placed against the patient’s body, and a flat disc on the other, to be placed against the physician’s ear. A prime example of this is a wooden monaural stethoscope from England circa 1880, with a bone/ivory disc attached (Image 2). These uniquely delicate materials raise questions about the practicality of this stethoscope, as well as how medical sound technology evolved through experimental uses of materials.

Image 2. A monaural stethoscope from England circa 1880 (artifact no. 2002.0503). This delicate stethoscope is made from a thin hollow piece of wood with a concave bell shape, attached to a flat disc made from bone or ivory. The materials of this stethoscope vary dramatically from the earlier Laennec model. This stethoscope exemplifies a unique use of materials to experiment with sound in medicine.

Even today, stethoscope designs continue to evolve and adapt to new sociocultural contexts. One of the more modern stethoscopes in the collection is a binaural stethoscope made in 2015 in Gaza (Image 3). As part of the Gila project for Open Medical Devices, Canadian physician Tarek Loubani and his colleagues developed this 3D-printed stethoscope that was cheap and easy to produce, while still having exceptional sound quality. They first made and used this stethoscope in Gaza, Palestinian Authority due to shortages of medical instruments. Along with the important historical context of the Gaza conflict, the creative use of everyday materials and the technical innovation of 3D-printing provides multiple ways of exploring the artifact.

Image 3. As part of the Gila project for Open Medical Devices, Canadian physician Tarek Loubani and his colleagues developed this 3D-printed stethoscope (artifact no. 2017.0002) using everyday materials, including plastic tubes from a Coke machine. The original, complete version was printed in Gaza in August 2015. This is the first stethoscope that Loubani used in practice.

Curators play an important role in shaping engagement and reflection through collections and exhibitions. As a student in Carleton University’s Curatorial Studies and Film Studies programs, I am trained, among other things, to examine how artifacts and storytelling can inform us about both our past and present. This project allowed me the opportunity to practice the work of shaping modes of engagement and discourse around artifacts in sites of knowledge.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!