Science Alive! Episode 10: Canada's First Car

Did you know that Canada’s first automobile had a horse and buggy design with a boiler and steam engine? On this episode of Science Alive, Dave talks with Curator of Transportation, Sharon Babaian about the steam buggy built by Quebec jeweller and watchmaker Henry Seth Taylor in 1867. Learn about the details of this unique vehicle and how its design was influenced by his skills as a jeweller.

Transcript

Dave: Canada’s first automobile was built in 1867. Meeting our talented tinkerer and his steam buggy on this addition of Science Alive.

Dave: I’m with Sharon Babaian, a curator of transportation here at the Canada Science and Technology Museum, now Sharon we are standing in front of Canada’s first car.

Sharon: Well yes, but it’s really not a car it’s actually more like a carriage. In fact early on they were actually called horseless carriages, so this is actually a steam carriage.

Dave: What year was this built in?

Sharon: 1867

Dave: Who built it?

Sharon: Henry Seth Taylor

Dave: What were some of the things about this that make it more of a horse’s carriage and less of an automobile?

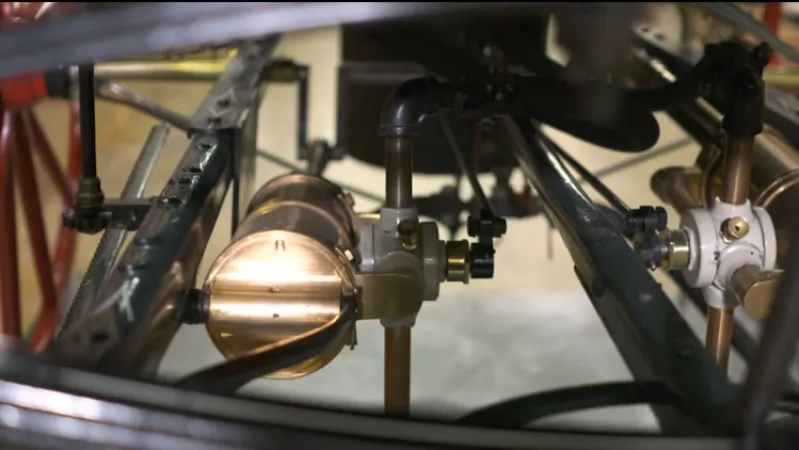

Sharon: The body work of it is essentially that of a carriage, it actually looks like a carriage. If you didn’t notice the boiler on the back of it or look closely underneath and see the cylinder and the pistons underneath, you would think that it’s a carriage. When you do look more closely at it, you see what makes it an automobile.

Dave: Now what would power this in 1867?

Sharon: Steam generated by either coal or wood, depending on what was around.

Dave: So you would put the steam in the boiler at the back, and then how would that actually make the vehicle move?

Sharon: It’s a scaled down version of a basic steam engine, a mobile or a locomotive steam engine in that it has two pistons, they are simple pistons in that they are not dual operating they are single operating. You control the amount of steam that goes into the pistons and that’s what controls the speed of the automobile.

Dave: How does the design of the throttle work?

Sharon: Basically it just opens up a valve that lets more steam in or less steam into the cylinders.

Dave: Are there brakes on this?

Sharon: No there were no brakes on it, that was the source of many stories about the vehicle. Turning down the throttle would cause the cylinders to slow down immediately and that would provide the breaking as long as you were not on a precipitous hill, you could probably stop fairly easily.

Dave: Would this be noisy?

Sharon: Oh I think so, most steam engines are noisy, I don’t know that it would be as noisy as a Harley Davidson but it would be noisy because pressurized steam would be escaping at various times and it probably wasn’t the highest quality of boiler so there probably would have been steam coming off of it. It’s also a carriage so it would raddle and shake, and there would be a lot of noise coming from the frame of the vehicle.

Dave: How fast could you get going on this?

Sharon: About 8-10 miles per house

Dave: It’s still a pretty good speed for 1867, how fast does a horse go?

Sharon: Maybe 5 miles per hour

Dave: Is there anything about this that really amazes you?

Sharon: Yes, the brass work, the cylinders, the actual engine of the car, these were made by Henry Seth Taylor who was a jeweller and watch maker so he knew how to work with metal and knew how to build things to very high standards and that’s what is required when building cylinders. You have to be able to trap the steam but still be able to move the pistons so you need very fine work. When you look at the cylinders you can see some of the decorative work that he did on them because he was also a jeweller and carriages were often embellished and made to look pretty and since he was putting an engine on it he decided to make it look pretty too. The cylinders survived from 1867 rusting away in a barn and they were completely functional when they were cleaned up and put into operation again.

Dave: Sharon the wheels on this thing are huge, why would it have such big wheels?

Sharon: Carriages in general had big wheels and that’s because the roads were not very good, bigger wheels tended to absorb more of the vibration, so it made travelling more pleasant because there were really only basic springs on carriages. That’s all the suspension that you have are these leaf springs and you see the independently sprung boiler, because the boiler would have been heavy which was unusual in a carriage because a carriage would not have had that weight back there.

Dave: Sharon Babaian, the curator of transportation here at the Canada Science and Technology Museum, thank you Sharon.

Sharon: You’re welcome

Dave: This was science alive!