A ride through the evolution of the bicycle (Part 2)

PART 2: The Velocipede, Ordinary, and Tricycle (1860s – 1890)

In honor of Bike Month (May 27-June 30), the Ingenium Channel is pleased to share a short series on the history of the bicycle, as supported by Ingenium’s beautiful collection.

As shown in part one of this history of the bicycle, early machines looked very different than the modern bicycles we know today. Today — in part two — we explore the next steps on this journey: The Velocipede, The Ordinary, and the Tricycle.

The Velocipede, or “The Boneshaker”

Michaux’s Velocipede, circa 1867.

At the 1867 Paris Exhibition, the French firm Michaux gained notoriety for developing the first commercially-viable version of a two-wheeled, human-powered bicycle: the Velocipede. While they were not the first to do this, Michaux was the first to tinker and perfect the design. When it was demonstrated at the Paris Exhibition, the Velocipede brought worldwide attention to the concept of cycling and sparked a craze of experimentation that would last until the early 1870s.

The big difference between the Velocipede and today’s bike was that you pedalled the front wheel directly. This arrangement significantly affected the steering: each time you pushed down on a pedal, the Velocipede tended to veer in that direction. Much like the Hobbyhorse, the pleasure of the experience wouldn’t last long — every bump in the road was transferred to your body through iron tires, wooden wheels, and solid iron frame. In English, the Velocipede was known as the Boneshaker.

A man coasts along with his feet up on the foot rests of his Velocipede.

The Ordinary

Starley Ariel, developed by James Starley in 1871.

Cycling evolved rapidly in the early 1870s, when English manufacturers greatly improved the original Boneshaker by developing a classic high-wheeled design known as the Ordinary.

The Ordinary popularized cycling as a sport, but it was a sport restricted to athletic young men who were willing to brave the dangers of the high-wheeler for the experience it offered.

This Ariel model designed by James Starley in 1871 is regarded as a landmark in the process. It represents the earliest attempt at making an all-metal bicycle, and it paved the way for the introduction of larger and larger front wheels.

This innovation meant a faster, smoother ride, but not a safer one. The big wheel’s tendency to turn back and forth with each push of a pedal made the bike prone to crashes.

A gentleman takes a classic header after running into the tail of a dog. Although slightly exaggerated, this business card pokes fun at the idea of how easy it was to go over the handle bars of a high wheel Ordinary.

More serious was the risk of “taking a header.” With your centre of gravity located directly above the hub, any sudden jolt could send you flying head-first over the handlebars.

BSA Ordinary bicycle, circa 1884.

1884 BSA Ordinary

Made by the Birmingham Small Arms Company, this machine, in its simplicity and elegance — and in the height of its 54-inch front wheel — represents the further development of the Ordinary bicycle.

Its huge wheel offered high speed and reduced vibration, but it also magnified one of the basic challenges faced when learning to ride a high-wheeler: how to get on and off.

Learning to mount and dismount meant falling, falling, and falling again, and called for a level of fitness (and a resignation to crashing) that was beyond most younger or older riders. And women simply could not ride an Ordinary wearing the voluminous dresses of the era.

Insurance advertisement entitled “Riding an Ordinary”, featuring three scenes from a ride on a high wheel bicycle. The insurance company thought you ought to be covered for your inevitable fall.

The Fane Comet, circa 1887

1887 Fane Comet

Made in Toronto, this Fane Comet represents the established high-wheeled bicycle as it was manufactured in North America.

A very light bicycle with a huge 50-inch front wheel and a tiny back wheel, it offered all the charms of the high-wheeler, as well as all its dangers — such as coasting down a long hill at speeds as high as 50 miles an hour and hitting an unexpected stone, brick, rut, or pothole.

More worrying was the fact that you could not keep your feet on the pedals when they were rotating at such speeds. This eliminated the possibility of backpedalling, which was the usual method of slowing down. You were forced to rely on your single spoon brake.

Given that you had to put your feet somewhere, high-wheeled bicycles like the Fane were designed with very low handlebars, the idea being that you put your legs right over them and straight out in front of you as you coasted downhill. This meant, in theory, that when you went off the front of the bike, you had a chance of landing on your feet instead of your face!

Riding down a hill could be dangerous for young men on high wheelers, who often rode without brakes. Here, the front rider takes a header as he runs into a flock of sheep. The rear rider has adopted the approved position for coasting with his legs over the handlebars.

The Tricycle Era, 1875–1890

While the Ordinary had become popular with young men, it was not a practical mode of transportation for most people. Manufacturers set out to capture this bigger market through a multitude of different tricycles. Frequently using the latest technologies, tricycles made it possible for many men and women to go cycling for the first time. Many inventions that were integral to the development of modern safety bicycles, such as continuous chain drive systems, ball and roller bearings, tangential spokes, and gearing systems came about during the Tricycle era.

To ride the Rotary you clambered over the tubular steel frame onto the seat, put your hands on the grips and used your feet to pedal the cranks. This turned the chain — it was the first use of a chain drive in cycling — which, in turn, drove the large 48-inch wheel.

1880 Coventry Rotary

James Starley was, arguably, the most important bicycle-maker of the nineteenth century. It was his 1872 Ariel that had established the pattern of the popular high-wheeled Ordinary. Starley was well aware that many more people wanted to ride than were willing to risk injury on a high-wheeler. For them, he designed the Coventry Rotary, which was the first commercially successful Tricycle.

With three wheels and a relatively long wheelbase, you didn't have to learn how to balance. Headers were unlikely. The metal wheels and hard rubber tires absorbed road vibration. Average speed was only a little slower than that of the Ordinary – and it had a brake.

Unfortunately, as with most tricycles, steering was somewhat erratic. And despite the stability offered by three wheels, cornering could be dangerous. You had to be very careful to reduce your speed and shift your weight as you turned.

Exeter Devon, circa 1885.

1885 Exeter Devon

The elaborate machinery of the 1885 Exeter Devon was intended to solve a number of the problems faced by riders of early Tricycles.

One problem was the tendency of machines with one driving wheel to turn in that direction as you pedalled, which made for erratic steering. To remedy this, the Devon had two chain drives to power both wheels.

A second problem was that the outside wheel had to travel further than the inside wheel as you turned, which meant that two wheels had to travel at two different speeds. If not, the inner wheel would jam and the Tricycle would turn over. To solve this problem, the Devon had a ratchet system that disengaged one wheel as you turned.

A third difficulty with Tricycles was that going up or down hills involved shifting your weight forwards or backwards, meaning that you were no longer in the most efficient posture for pedalling. The Devon was designed with an unusual pivoting swing frame, intended to keep you in the perfect pedalling position.

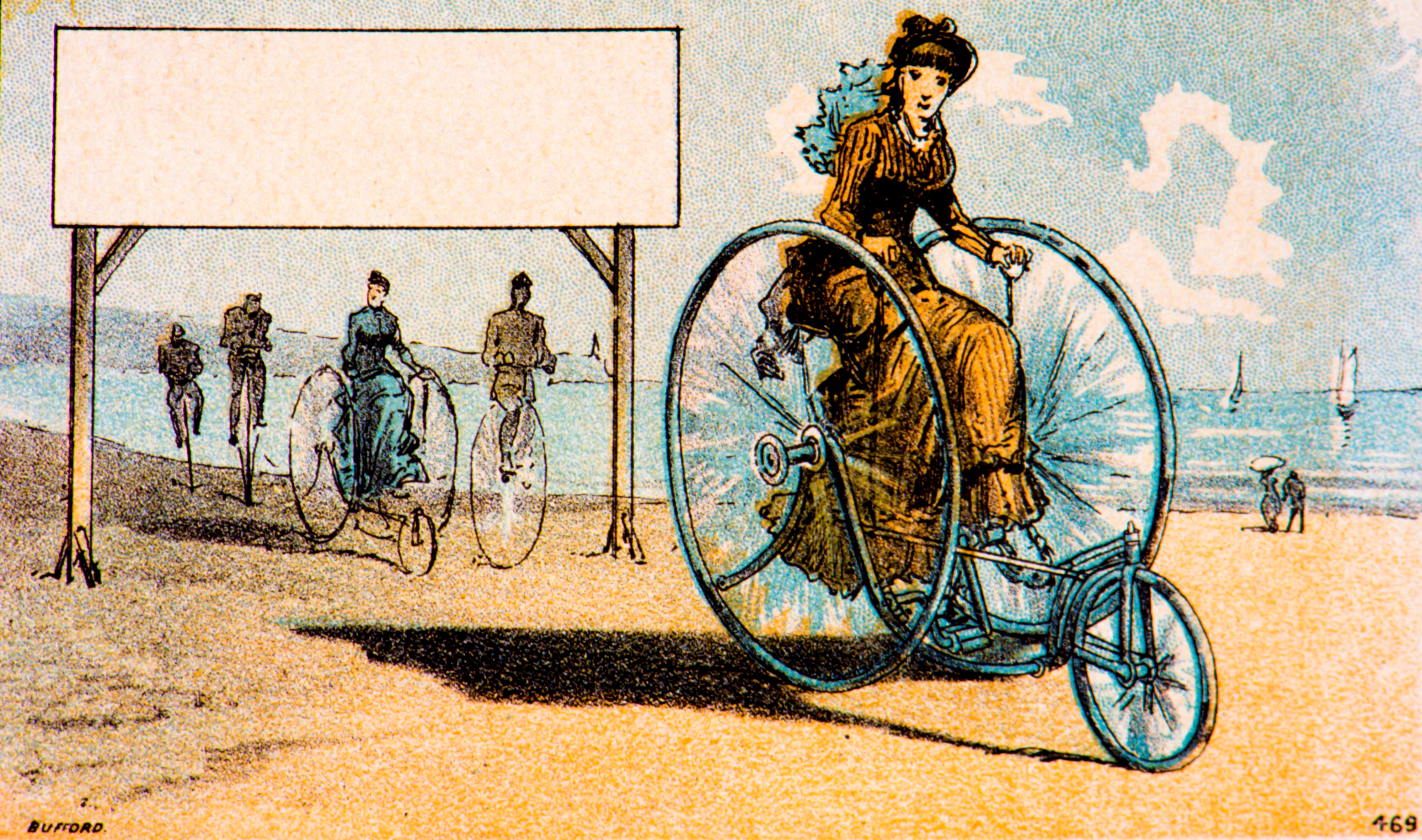

Ladies enjoy a tricycle ride in the company of three men on high wheel bicycles, 1880s.

Royal Salvo tricycle, circa 1888.

1888 Royal Salvo

Another popular tricycle design was James Starley’s 1888 Royal Salvo, with an innovative “balance gear” that eliminated Tricycles’ tendency to turn towards a single driving wheel. This made tipping over while turning much less likely.

Partly because of the ride, partly because the balance gear eliminated an extra chain, and partly because of the chain guard, the Salvo was the vehicle that opened cycling up to respectable women for first time. So respectable were these machines that Queen Victoria bought two.

Though these machines would soon by eclipsed by the faster, more stable, safety bicycle, the designs we use today are very much in debt to this experimental tricycle period.

This text is adapted from the 2015 Google Arts and Culture virtual exhibit, Cycling: The Evolution of an Experience, 1818-1900.