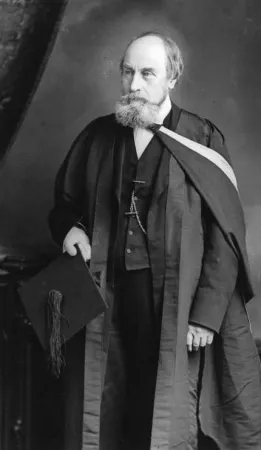

John William Dawson, the man who made McGill

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

Ilana Reimer

Algonquin College Journalism Program

Sir John William Dawson was just as comfortable teaching in a classroom at McGill University as he was precariously scaling a cliff in search of rock samples. A renowned geologist, Dawson was the first Canadian scientist to gain a worldwide reputation for his work. His efforts, both in research and as the principal of McGill, helped lay the foundations for the Canadian scientific community during the 19th Century. A modernist in both science and education, Dawson firmly believed that women should be able to receive the same education as men. He played a key role in allowing women to attend McGill.

Born in 1820 to Scottish immigrants, Dawson was raised and educated in Pictou, Nova Scotia. After graduating, he continued studying on his own. He hungrily consumed any books on geology and natural history that he could find. He also started collecting minerals, shells and rocks from the countryside surrounding Pictou to add to his impressive collection.

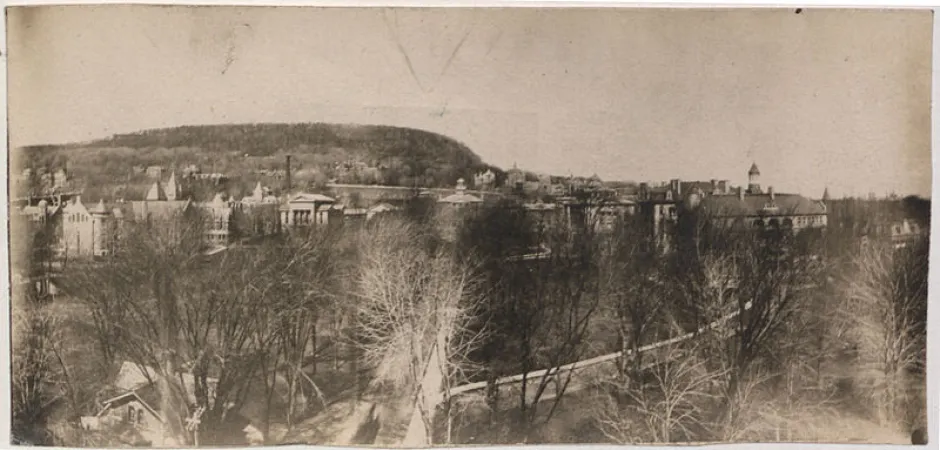

Dawson became principal of McGill University in 1855 and spent 38 years making the school one of the world’s recognized universities. Besides his administrative duties, Dawson worked to revitalize the campus grounds, taught multiple classes and founded McGill Normal School to educate teachers on how to prepare their students. To this day he is now known as “the man who made McGill.”

Dawson was a leading expert on early fossil plants and became a Canadian pioneer in microscopic studies of fossils. He was a Christian and strong anti-Darwinist. From his knowledge of fossil evidence, he could not see that new species had evolved out of earlier ones. Thus, many of his books offered technical criticisms against Darwinism. His wide-spread reputation not only served McGill well, but helped establish up-to-date science institutions in Canada that offered higher degrees and research.

In 1884 Dawson was knighted for his public services. He died in 1899 and was inducted into the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame posthumously in 2004.