How the St. Lawrence Seaway made trade go swimmingly in Canada

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

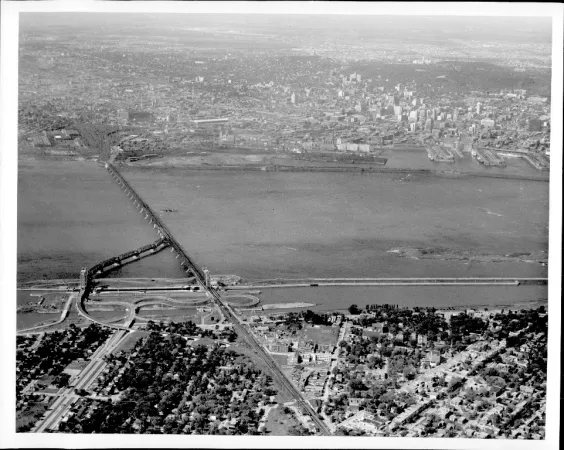

The St. Lawrence Seaway is a massive system of locks, canals and channels that link the great lakes to the Atlantic Ocean. In essence, it’s a trade route that helped anchor Ontario and Quebec as the economic powerhouses they are now.

The seaway became open for commercial use in 1959, costing a total of $470 million dollars – most of which was funded by the federal government. From Montreal to Lake Erie, the creation of the route was a serious undertaking. The National Research Council made models to visualize the project, complete with hydraulic simulacra of waterways. Many highways, roads and small towns had to be relocated to make room for the seaway.

Although there was a very important economic incentive for the system, the NRC learnt a lot from the planning and execution of creating the route. They had to flood 15 thousand hectares so a lot of research went into full-scale burns, in order to raze certain parts along the seaway to the ground. Controlled burns of abandoned communities and their buildings also gave the NRC new insight into fire safety, especially in the context of city planning. They began classifying different kinds of ice and how to break them, as well. All of this consequential research benefitted other countries too, as many safety regulations today are based off research from the creation of the St. Lawrence Seaway.

The NRC is still doing research on the seaway to this very day, continuing to discover new properties of ice there, but also on subjects of energy, like hydroelectricity. In 2014, they published a paper on hydrokinetic resources based on their findings from the route. The St. Lawrence Seaway is capable of harnessing hydroelectric power without the use of dams or pentlocks, a feat few countries in the world can lay claim to.

By: Jassi Bedi