Rising from the Grave: “Deadplay" and Video Game Preservation

In September 2016, I started a master’s degree in Public History at Carleton University. My research was supposed to explore the representation of American foreign policy in video games, but things changed. As part of the degree’s requirements, I had to complete a summer internship. I was very lucky to be awarded such an internship at the Canada Science and Technology Museum (CSTM). Since my research was on video games, I was given the opportunity to do work related to that subject. My task seemed simple enough: start assessing the software in the museum’s artifact collection and write a research report on the preservation of born-digital artifacts (i.e. objects whose primary and original form is digital). I soon discovered, however, that while much had been written on the subject of digital preservation, there existed no widely accepted methodologies or “best practices” documents for how to effectively preserve born-digital artifacts—particularly in the museum context. Needless to say, I had my work cut out for me. When I started reading up further on the subject, I was struck by how James Newman—Professor and Senior Lecturer in Film, Media, and Creative Computing at Bath Spa University—started his monograph Best Before: Videogames, Supersession and Obsolescence. “Videogames are disappearing,” he writes: “No really, they are.” He proceeds to explain that, because of bit rot, which is the degradation of housing media and the digital information stored on them—and the degradation of the platforms (consoles, computers, etc.) and peripherals used to access this information—video games eventually become unplayable. On top of that, the video game industry’s practice of continually developing new games and consoles causes older ones to become obsolete. The more I read, the more I realised how right Newman was. This realisation caused me to change the focus of my research. I would now investigate video game preservation and attempt to propose a solution.

"Videogames are cultural heritage artifacts worthy of preservation . . .

Deadplay suggests a first essaie in ensuring videogames are adequately preserved for future study."

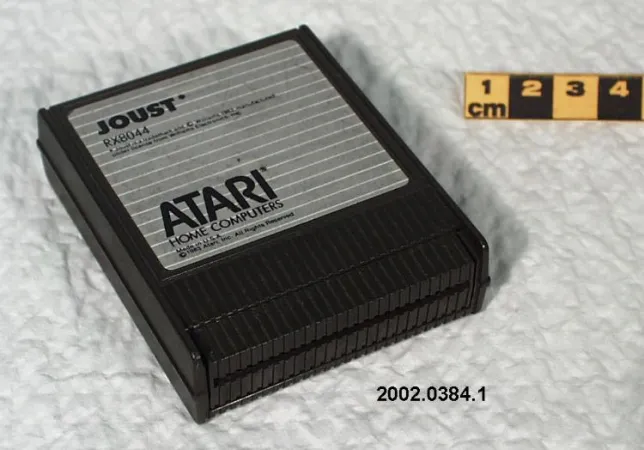

Following the completion of my internship, I was awarded the Garth Wilson Fellowship at the CSTM, enabling me to continue working on my new research from within the museum. I decided to focus on two games I found in the CSTM’s collection during my internship, Joust (artifact no. 2002.0384.001) and Seven Cities of Gold (artifact no. 1995.0822.029), and develop a methodology to preserve them. My first instinct was to play the games. After all, video games are meant to played. The museum had the platforms for both games, but there was a serious problem: they had not been powered up in over 25 years. Computers and game consoles have capacitors which, if they are not powered up periodically, have a high risk of exploding. This meant that I could not play either game at the CSTM. Newman’s warning suddenly became tangible and I realised how dire the situation was. To prevent what I came to see as the death of video games, I decided to begin developing a methodology capable of preserving video game technology as well as video game play.

My Master’s major research project culminated in the creation of a podcast and website which investigate videogame preservation and proposes some solutions to this complex and pressing issue. It is entitled Deadplay and can be accessed through the project’s website, www.deadplay.net. Here, you can find the podcast’s audio files, its complete script, a further reading list, and some complementary material—all of which can be annotated through an embedded Hypothes.is overlay.

Videogames are cultural heritage artifacts worthy of preservation. They are both digital and physical, inspire and are inspired by other forms of media, reflect and are products of our cultures. Deadplay suggests a first essaie in ensuring videogames are adequately preserved for future study.