Margarine: The complex story of a simple spread

The production of cheap margarine was a boon to poorer consumers. Although some countries adopted it easily, other countries tried to eliminate it or limit its availability. In the 1870s, margarine began to spread (pardon the pun) to other countries.

Margarine: The complex story of a simple spread

When Canada was re-negotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement in the late 2010s, a major sticking point was the supply-management issue of Canada’s dairy industry. This wasn’t the first time that Canada’s dairy policies have caused tension between its neighbours; Canada’s dairy industry has been a powerful voice for policy in the past.

The quest for a better butter

Due to a butter shortage in France during the 1860s, Napoleon III offered a prize to anyone who could create a cheaper substitute for butter with a long shelf life. This could be used by lower-income families, as well as the French army when they were in the field. Butter tastes great, but it has one disadvantage for travel: it needs to be kept chilled, or it will spoil. Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès, a French chemist who had been studying foods, processed beef fat and milk to make a bland, neutral spread that could serve as a butter substitute, and was awarded a prize in 1870. Unfortunately, he never made much money from his butter substitute, due to international patent regulations and its low domestic popularity. But other countries took notice.

I can believe it’s not butter

Mège-Mouriès must have found it frustrating that he lived to see margarine become an international issue; sadly, he died penniless in 1880. The production of cheap margarine was a boon to poorer consumers. Although some countries adopted it easily, other countries tried to eliminate it or limit its availability. In the 1870s, margarine began to spread (pardon the pun) to other countries. At the request of the dairy industry, the American government passed the Margarine Act in 1886. This act applied a heavy sales tax on the product, and an expensive licensing fee in an effort to make margarine more expensive than butter. Several states went a step further, and banned margarine outright.

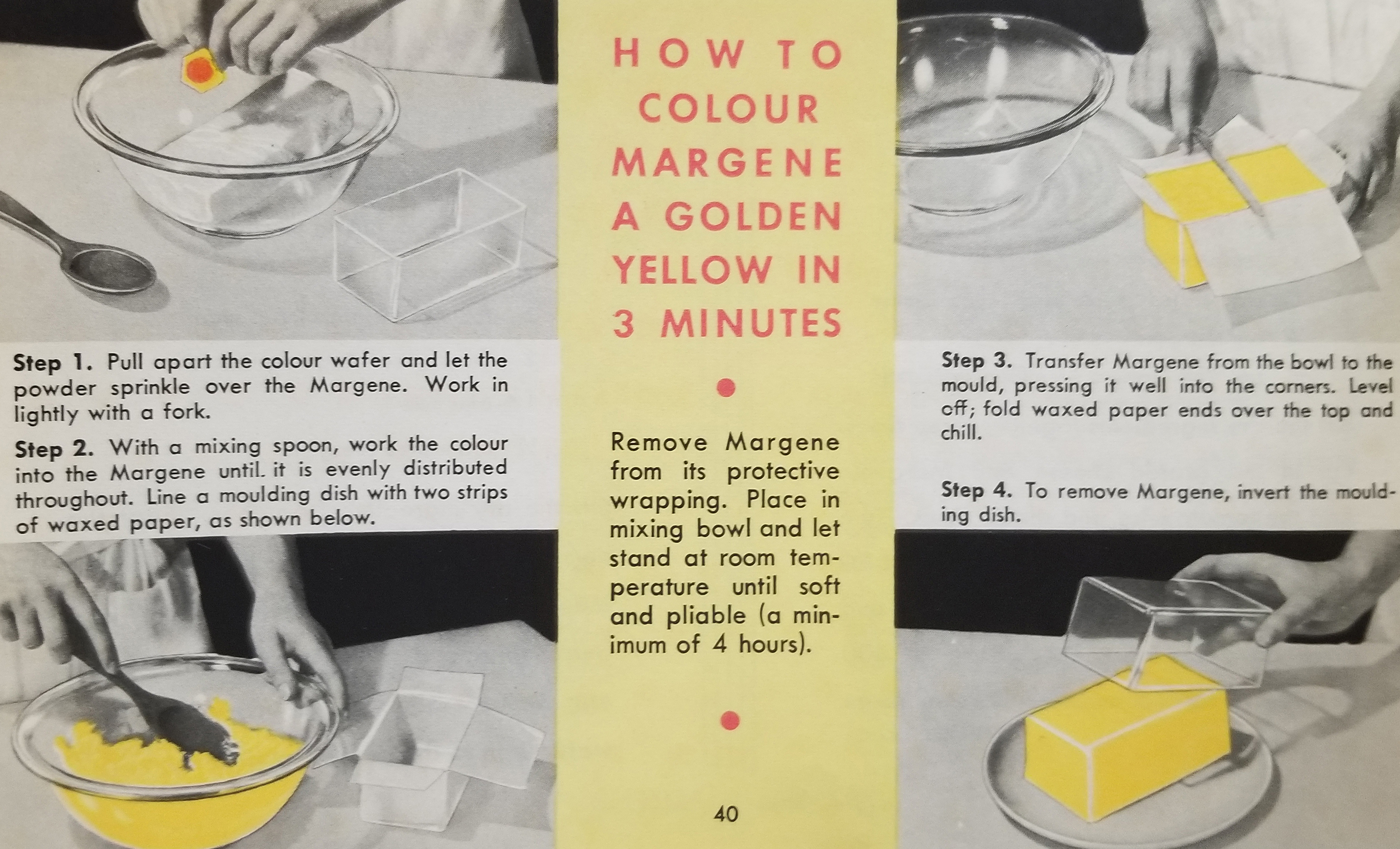

Instructions for how to add the company-provided dye to colour your margarine – the manufacturer’s way of circumventing restrictions on coloured margarine.

The Canadian government banned margarine for sale outright in 1886. Dairy farmers were a strong lobby because they were reliable voters, while those who benefited from margarine’s low cost — such as mothers, the poor, and men who didn’t own property — couldn’t vote. The ban would be relaxed from 1917 to 1923, when the war caused a shortage in butter supply. When the ban was federally repealed in 1948, dairy farmers objected vehemently.

I’se the b’y that makes the margarine

Other countries eagerly adopted margarine, whether or not they had a strong dairy industry. Oil from seals, whales, and fish, which had once been used as lubricants in machines and factories, had been replaced by petroleum-based greases. These products could now be converted into a cheaper butter substitute. Newfoundland, which was not yet a part of Canada and had important sealing and fishing industries, lacked the climate to support a dairy industry, and most of their butter was imported from Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. Following the success of other nations with similar economics, Newfoundland entered the margarine industry.

Production of margarine in Newfoundland began in 1883, initially using oils from seals, whales, and fish. But it was Newfoundland’s third margarine company that created a political controversy. Sir John Crosbie, the Minister of Fisheries for Newfoundland, was inspired after a trip to Denmark, where he learned that in spite of a strong dairy industry, they had a successful margarine industry as well, based on oils from the fisheries. In 1925, he founded the Newfoundland Butter Company; an ironic name, given that they never produced any butter. The company had a unique promotion to generate interest — some of the first tubs contained gold or silver coins. The government passed legislation that imposed a 6 per cent import tax on margarine in the same year the factory opened, which would benefit Crosbie and the other margarine manufacturers, and Crosbie was also accused of using his political influence to sell his margarine to public institutions in the Dominion.

Just as Prohibition of alcohol created a black market for Canadian liquor in the United States, the prohibition on margarine created a black market for bootlegged Newfoundland margarine in Canada, as it cost half as much as butter. When Newfoundland entered negotiations with Canada to join Confederation in 1948, a major sticking point was the margarine issue. The British North America Act was amended to include two references to margarine: one to legalize margarine production in Canada, and another to prohibit its exportation to the other provinces.

A question of colour

When produced, margarine is a pasty white colour, which looks unappetizing. Butter gets its rich colour from carotene in the grass that cows eat. Beginning in the 1870s, margarine manufacturers added yellow colouring to make their product look like butter. The dairy industry thought this was misleading, so provinces banned the sale of yellow margarine. In the United States, some states went one step further, ordering margarine to be coloured pink, while other states proposed making it red, brown or black. The United States Supreme Court later ruled the “pink laws” as unconstitutional in 1898.

Even after margarine was legalized for sale in Canada, some provinces mandated it to be a bright yellow or orange, while others made it illegal to sell a coloured product. Some manufacturers got around this law: they sold margarine in a plastic sack with a tab. Pressing on the tab released yellow food colouring, which the consumer would mix into their margarine at home, a process that took around 20 minutes. Incidentally, cows fed a corn-based diet (as opposed to grass) do not get the carotene required to colour the butter produced from their milk, making it look like unaltered margarine; the dairy industry considered artificially colouring this butter to be acceptable.

A recipe for “Dream Cake” from a margarine cook book. Bon appetit!

Most provinces enacted rules that ensured margarine wouldn’t be mistaken for butter: restaurants had to advertise that they were serving margarine; it couldn’t be mixed with butter in restaurants; when sold in grocery stores, it needed to be clearly labeled; and the product couldn’t be marketed in such a way that implied that it was a dairy product.

After Ontario passed a law repealing the ban on coloured margarine in 1995, Quebec remained the last holdout. While most provinces had dropped their prohibition or chose to not enforce the laws, the dairy industry was very influential in Quebec. But in 2008, the government finally relented, as did the dairy industry, noting that butter had regained popularity following the reversal in the trend that promoted margarine as a healthier alternative — it was part of a broader trend at the time to eat food that had undergone less processing.

Today, margarine’s legacy lives on, and consumers can choose whether they prefer butter or margarine for themselves.