Footprints and fingerprints: Reflections on a shoe-forming press from the Kingston Penitentiary

Have you ever thought about how far you’ve travelled and where you’ve left your mark? What about the people who have left their marks on your shoes?

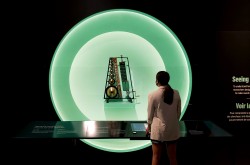

This forming press (circa 1950) was used in the Penitentiary Boot and Shoe Store in the Kingston Penitentiary.

As a student of Public History, I am interested in learning about how the history of things has influenced us. I had the chance to think about this during my practicum at Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation. My research project centred around the history of prison labour in Canada, with specific emphasis on the Kingston Penitentiary. In addition to looking at historical sources, I had the chance to look closely at several artifacts that came from the Kingston Penitentiary. Being able to examine these artifacts helped me feel closer to the people whose lives were changed by their stay at the Kingston Penitentiary, and to better understand what their lives on the inside might have been like.

One of the artifacts that impacted me the most was a shoe-forming press from the 1950s. It measures 162 cm by 46 cm, and was able to manipulate metal to match certain measurements. The press was made by the United Shoe Machinery Corporation, which provided Canadian trade workers with machinery. At the time, their machines would have been found all over Kingston Penitentiary; they would have been used by inmates working in the trades, such as metal working and shoemaking.

A supervisor examines the an inmate’s work at a shoe-making workshop inside the Kingston Penitentiary, circa 1950s. A man can be seen operating a shoe press in the background.

Kingston Penitentiary opened on June 1, 1835 and received its first six inmates the same day. Modeled after the Auburn prison system, Kingston Penitentiary offered separate sleeping cells, but prisoners would work together during the day. There was a wing that was solely dedicated to workshops, where outside businesses could set up and have prisoners work there. One of those shops was the Penitentiary Boot and Shoe Shop. There, machines such as the forming press were used to make shoes for the penitentiary, other penitentiaries across Canada, and even for retail sale. The jobs that prisoners had at Kingston Penitentiary are similar to the jobs prisoners have today. There are programs that help prisoners gain skills they can use once they are released, as well as working on maintaining the daily tasks in the prison. However, prisoners today are only paid $1.95 or less an hour for their labour — compared to 40 cents per day in 1869 — and they are ineligible for many of the social programs we have in place.

The shoe-forming press helps amplify the relationship between prisoners and the outside. We can see that these prisoners made products that could leave the prison, while the workers themselves stayed behind. The workers may have been incarcerated for long periods of time, and likely didn’t get to see the impact of their work. All these years later, I appreciate the opportunity to reflect on this relationship, and see how these artifacts — and those who used them within the walls of the penitentiary — made their mark on the footsteps of many Canadians.