Music meets public history and digital humanities in Garth Wilson Fellowship

As a student in Carleton University’s Public History program, I have been trained, among other things, to look at the forest — and not the trees. Larger themes, messages across communities and through history, and trends in the social and cultural development of different publics are all of concern. Conversely, my work specializing in digital humanities in that same program has me focusing on the details. Great meaning can come from the smallest data point, and should be examined with its whole context. My position as the Garth Wilson Fellow at Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation has allowed me to do both at the same time.

With a long-running interest in music, I had the opportunity to dive into a project that combined music with public history and digital humanities. I worked with Ingenium curators David Pantalony and Tom Everrett — and alongside historians and researchers from Paris and Berlin — to add Canadian artifacts to an existing acoustics digital database. I had the opportunity to discuss the ontology of the database, to contribute to it, and to learn from experts in the field about the future of digital databases — and how to improve them.

The project was every bit the forest that my public history training had taught me to expect. Through conversations with David and Tom, and by participating in international meetings, I learned firsthand about how museums deal with digital catalogues and databases. We discussed ways to create a digital database and exhibition that is as tactile and object forward as possible. In a museum climate where the digital sphere is more important than ever, our conversations were enlightening and heartening; they gave me a real sense of where my field was going and how I could contribute to it.

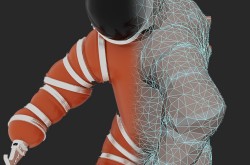

More than that, this same project — and my work in the Fellowship — allowed me to work with the smallest details in the way that my digital humanities training has taught me to appreciate. Outside of merely discussing the nuts and bolts of a digital database, the data entry aspect of my Fellowship was really valuable. By entering objects and collection profiles into the database, I was given a chance to dive deep into the details of these material artifacts. I was able to develop an appreciation for the importance of material history — even though I was disconnected from the physicality of those objects due to pandemic restrictions at the Ingenium buildings. I learned to find meaning in the details of dates, of measurements, and of provenance. I learned that even the photos of artifacts should be treated as artifacts!

This is what I like best about digital work: handling the data is a lot like handling the actual objects. The details contain real meaning and real history; even the ones that appear insignificant are multifaceted upon a more serious look. Digital work allows each tree — each data point — to generate meaning independently, and then to be viewed as a part of a larger whole.

My major research project for my MA is about combining close reading and distant reading to learn more about the public history field as a whole. It is about stepping back from the field and looking at its thousands of published articles all at once using digital tools, all in order to understand its trends and philosophies over time. I could not have asked for a better fellowship project to give me clarity about how to do this. Additionally, as I prepare to start my PhD in Cultural Mediations and a diploma in Curatorial Studies at Carleton University, I will take this experience of working in a museum environment with me to inform my further work and education in this field.

Though this work was not without its difficulties — learning on the job is much harder when working from home and so disconnected from the museum space — the opportunity to dive into digital archives, and to work and contribute to a living database, has been incredibly valuable.