Award profile: Finding cultural connections through our shared mathematical heritage

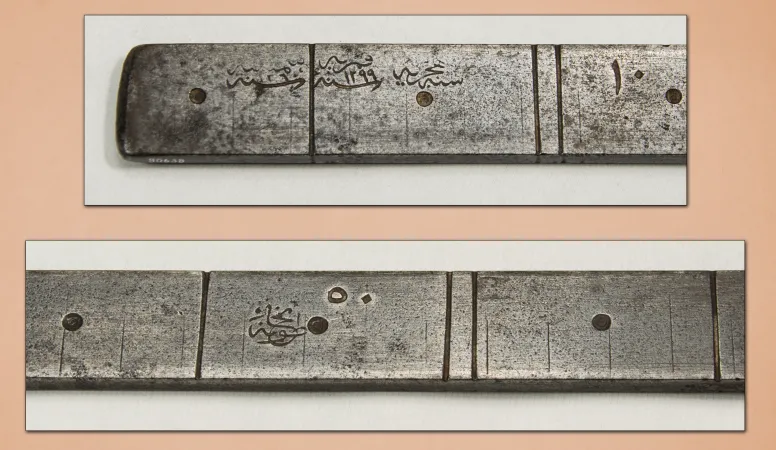

The Petrovic Collection at the Canada Science and Technology Museum is a collection of over 130 mathematical instruments from the twelfth to nineteenth centuries. These instruments came to the museum in 1980 from Dr. George Petrovic, a Serbian-born architect who collected them in order to document the connections between mathematical practice and architecture in the eastern Mediterranean regions, as well as countries that were once part of the Ottoman Empire.

The collection is now at the centre of an ongoing research project by Hasan Umut (Ingenium-McGill Fellow for the History of Science, Medicine, and Technology, PhD Candidate), Assia Kaab (Head Researcher, Guild of St. Stephen & St. George, UK), and David Pantalony (Curator of Physical Sciences and Medicine, Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation). All three were recently honoured with an Award of Outstanding Achievement in Research by the Canadian Museums Association.

The Ingenium Channel sat down with Hasan, Assia, and David – to talk to them about their work with the Petrovic Collection and the surprising connections it created with a diverse community of scholars.

David Pantalony, Curator of Physical Sciences and Medicine, Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation.

Ingenium Channel: In your own words, describe the scope of your research project.

David: Our main goal was to learn more about the use and context of this collection — the Petrovic Collection — that had been in the museum for several decades, yet we knew little about it. So the collection was somewhat mysterious; it was sitting there waiting for the right people to see its significance. My colleagues and fellow award winners, Hasan Umut and Assia Kaab, played a critical role in helping to bring context to the Petrovic Collection. Hasan is working on a dissertation about Islamic astronomy, within the broader context of Islamic Studies, so this collection covers many regions and periods that he’s familiar with. Assia Kaab, through her knowledge of classic architecture and stone masonry, knew how many of these instruments were actually used by builders, surveyors and architects.

Assia Kaab, Head Researcher, Guild of St. Stephen & St. George, UK.

Assia: I joined the team in the summer of 2016, and used my expertise in historical architecture to research the use, authenticity, cultural value, and potential exhibition subjects of the Petrovic Collection. It was an adventure! From speaking to embassies to international collectors, I learned a lot about Ottoman architecture and the similarities I share with them as a Vitruvian architect.

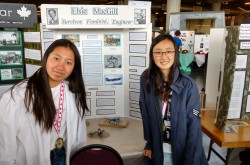

Hasan Umut, Ingenium-McGill Fellow for the History of Science, Medicine, and Technology, PhD Candidate.

Hasan: I am a PhD candidate at McGill’s Institute of Islamic Studies, where my dissertation is about theoretical astronomy in the early modern Ottoman Empire. I am also interested in other subjects of the history of science, including metrology and scientific instruments. Thanks to the fellowship I was granted by McGill University and the Canada Science and Technology Museums Corporation (Ingenium) in 2016, I started working on the George Petrovic’s metrological collection. The scope of our research is to analysis the Petrovic’s metrological instruments in the museum in order to understand how scientific instruments were transferred across cultures, centuries, and even continents. We also aim to understand the link of the formation and transmission of Petrovic’s collection, with the scholarship he produced when he was a professor of architecture at the University of Belgrade.

Ingenium Channel: If you were speaking with an average museum visitor — or a random Canadian — how would you explain the over-arching significance of this research?

David: I would say the most important thing is that these are actually very simple mathematical tools that were able to do complex things – they teach us about all the skills and math underlying so much of our surrounding world. In this case, the instruments were used in architecture, building, and surveying, and even for measuring in tailor shops and marketplaces.

In the Islamic world, we have these beautiful, sophisticated buildings; to think of these tools as being a key part in making them is quite remarkable. We don’t pay enough attention to mathematics, but these kinds of instruments are always in the background doing work, and they are surprisingly stable across different places and time periods.

Assia has studied the history of these types of practices in masonry, so she really brought to this project how these tools were actually used. She helped us connect the collection to the study of architecture and stone masonry — which are conservative traditions through generations of practitioners.

So these tools really show how mathematical practice can be shared across multiple cultures. Many of these instruments, in fact, came from regions that today suffer much conflict, and yet our research shows how these instruments point to a shared mathematical heritage. As a museum, it is important for us to explore these connections, what we have in common, and to collaborate with researchers such as Hasan and Assia who are from these different parts of the world that make up the diverse fabric of Canada. In the end, we discovered that this was a very Canadian project.

Assia: The shiny triangle pieces are more than measuring tools. They are keys to a forgotten world so rich in its beauty and splendour that, to this day, we remain in awe of its brilliance. To this day, I find myself astonished at how similar we are to our Ottoman counterparts. This research subject goes beyond the artifacts. It isn’t just about a collector and his collection, it is about the fascinating journey these artifacts took to reach us.

Hasan: The main significance of our project is two-fold. First, it aims to emphasize the connectedness among the cultures in the pre-modern East Mediterranean region in terms of mathematical practicality. Secondly, immigration is a natural phenomenon in Canadian context, but our research should be one of the few, if not the only, examples that focus on the “immigration” of scientific instruments that were produced or used in the Ottoman Empire, which ruled a large portion of the East Mediterranean until the first quarter of the twentieth century, to Canada.

Ingenium Channel: Tell me about a surprising or memorable moment that happened throughout the course of your research.

David: The most memorable moment for me was over five years ago when I invited Professor Jamil Ragep (Canada Research Chair in the History of Science in Islamic Societies at McGill) to see this collection. Prof. Ragep, a renowned scholar in the field, was surprised to learn about it, and was intrigued enough to bring his students from Montreal. Hasan came on that day too, and there was much discussion and debate about one of the inscriptions on a Rule made in Istanbul, but attributed to Benghazi. In fact, in that short session with the collection many questions were raised. I knew at the moment that we had a collection worthy of more study. When our McGill fellowship started in 2016, we jumped at the opportunity to get Hasan here to help further this research.

Assia: While speaking to a collector’s group in Germany, I was told about an ancient Andalusian manuscript that detailed a completely unexpected use of the tools. I had to get speakers of Old Arabic to join me in translating the relevant sections, to uncover that the tools are about 200 years older than I thought they were — and originally used as a farmer’s levelling tool!

Hasan: I had many fond memories during my research in the museum. Let me tell one of them: I should express my thanks for the hospitality, help, and cooperation of all the people in the museum. David, Assia, and I presented some of our findings at the Ingenium Annual General Meeting for 2017, held at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto. I was so pleased to see that the members of the three museums under Ingenium from different backgrounds and interest, were so curious about our project. It was really encouraging. I thank you all!

Ingenium Channel: Where do you hope this research will lead?

David: First, these instruments and the worlds they were part of (and created) deserve to be shared with wider audiences in Canada and around the world. This could come in the form of collaborative international exhibits, online projects and more publications. We have also started a second phase of research related to the story of Petrovic the collector in the 1960s and 70s. The Serbian Embassy has been helping us connect to key sources in Belgrade.

Assia: Part of my research was to explore possible exhibition subjects for the collection. There is the Ottoman route, the French connection, and the Andalusian origin story. Either way, I would be happy to see the collection displayed for the public.

Hasan: We have plans to organize an Ottoman instrument/architecture workshop, as well as to continue our research on the relationship between Petrovic’s publications and the provenance and evolution of the collection. We hope that all our research will draw historians of science and architecture, as well Ottomanists to this collection, so that the Petrovic collection will be subject to collaborations with institutions from different parts of the world, which have similar collections.

Watch a short video about the Petrovic Collection – a collection of more than 130 mathematical instruments – at the Canada Science and Technology Museum.

Transcript

The Petrovic Collection at the Canada Science and Technology Museum is a collection of over 130 mathematical instruments from the twelfth to nineteenth centuries. These instruments came to the museum in 1980 from Dr. George Petrovic, a Serbian-born architect who collected them in order to document the connections between mathematical practice and architecture in the eastern Mediterranean regions, as well as countries that were once part of the Ottoman Empire.

The collection is now at the centre of an ongoing research project by Hassan Umut, Assia Kaab, and David Pantalony. These researchers found the collection provided surprising connections to a diverse community of scholars – from countries such as Turkey, Serbia, and Iraq – revealing a shared mathematical heritage and potential for further collaborations.

Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation is thrilled to be the recipient of the 2018 Canadian Museums Association’s Award of Outstanding Achievement in Research, for research activities carried out in museums or applied to museum practice that contributes to the development of new knowledge and understanding.