A ride through the evolution of the bicycle (Part 3)

PART 3 – The Dawn of the Safety Bicycle, 1880s - 1900

In honour of Bike Month (May 27-June 30), the Ingenium Channel is pleased to share a short series on the history of the bicycle, as supported by Ingenium’s beautiful collection.

As shown in parts one and two, even though improvements on early designs opened up cycling to a greater number of people, the high wheel bicycle was dangerous, and not everyone was willing to ride a tricycle. Many riders wanted something as fast and fun as an Ordinary, just a little safer.

In part three, we will look at how manufacturers attempted to meet this demand with various modifications of the high wheeler, eventually producing the Safety Bicycle we know today.

HB Smith Star, circa 1881.

1881 HB Smith Star

The U.S.-made Star bicycle, introduced in 1881, represents one of the more unusual responses to the safety risks that the high-wheeled Ordinary posed. In essence, this machine was a “reversed” Ordinary, with a large 48-inch driving wheel at the back, and a small 22-inch steering wheel at the front.

Having the small wheel in front made headers less likely, while having the centre of gravity between the wheels offered better lateral balance. Although steadier, because there was so little weight on the small front wheel, steering was uncertain.

Slipping sideways on wet pavement was another potential danger. And although it was difficult to go over the handlebars, if you were unlucky, this bike could still tip over backwards.

Geared Facile, circa 1885.

1885 Geared Facile

The Geared Facile introduced in 1885 combined three design concepts in an attempt to provide a bicycle that was just as fast as the original Ordinary, but safer.

First, raked forks were used to move the riding position and therefore the centre of gravity behind the front hub and between the wheels. This seating position made it difficult to reach regular pedals; instead, you pedalled levers behind and below the hub.

Second, the Facile used a much smaller driving wheel than the original Ordinary: it was only 40 inches. If you took a header, or went over sideways, you didn’t have as far to fall.

Third, the Facile employed a relatively large 25-inch rear wheel. Its size meant it could roll over stones or other obstructions, rather than skipping to the side, causing you to crash.

Finally, the Facile used “sun and planet” gearing to make up for its small driving wheel. With this arrangement, as one gear circled the other, the rim turned more than once. By “gearing up” you could get the equivalent drive that was possible with a wheel as large as 57 inches. The result was a safer ride without being forced to sacrifice speed.

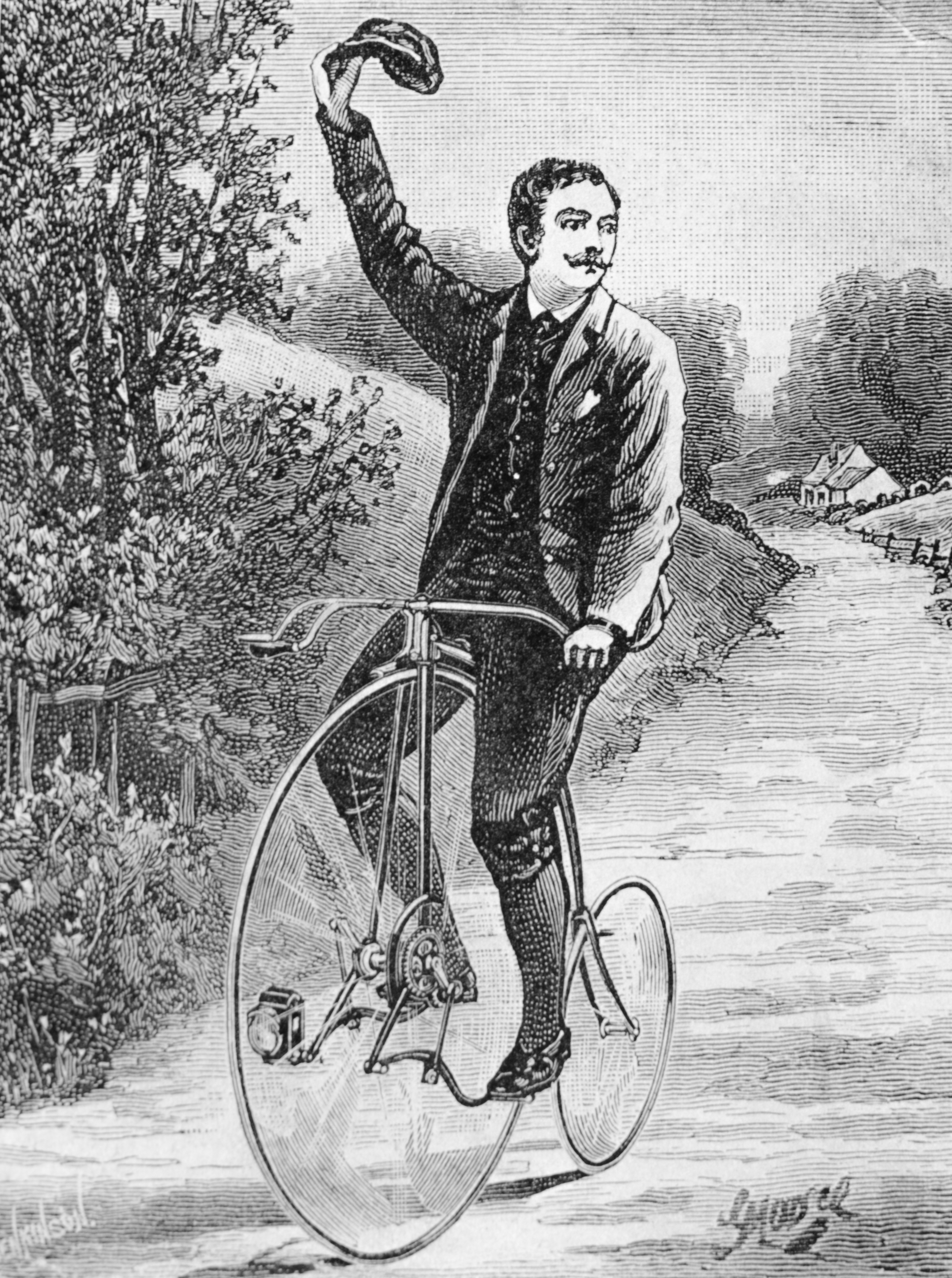

Illustration of a man riding a Geared Facile in the 1880s. Note the levers and gears at bottom.

Columbia Dwarf Safety, circa 1884.

1884 Columbia Dwarf Safety

The Columbia Dwarf Safety was the U.S. version of a British design known as the Kangaroo. It continued the trend in Safety Ordinaries towards smaller wheels and compensating machinery — in this case, using the type of chain drive that was common on Tricycles.

The front wheel of this model was only 38 inches high, so mounting was easy and you could still reach the ground with your feet, and the Dwarf’s size lowered its wind resistance. The machine also allowed you to gear up to get the equivalent drive of a big wheel, meaning you could enjoy a very fast ride. On the downside, the small wheels, hard rubber tires, short wheelbase and chains made for non-stop vibration along the way.

True Safety Bicycles

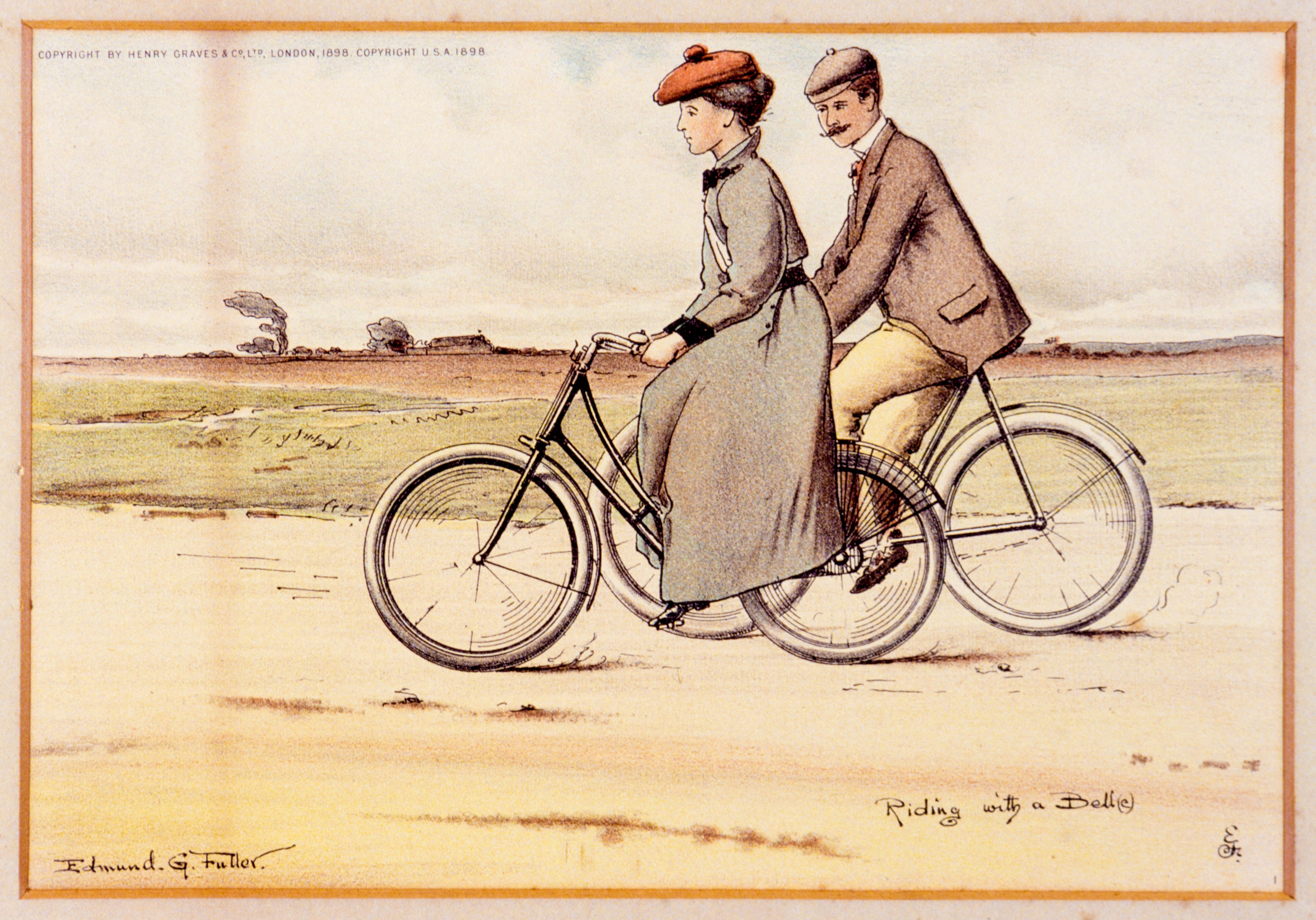

In the 1890s, bicycle manufacturers standardized production around the design of the diamond frame Safety Bicycle. They added the pneumatic tire, providing a ride that was faster and more comfortable than ever. They applied techniques of mass production, making bicycles cheaper than ever.

The result was a world-wide bicycle craze in which millions of men, women, and children went cycling for the first time.

Cartoon depicts the looming battle between Safety Bicycles and Safety Ordinaries like the Kangaroo. Artist G. Moore makes it clear who the winner will be.

Lawson Lever Safety, circa 1876.

1876 Lawson Lever Safety

The first bicycle to which the word “safety” was commercially applied was the 1876 Lawson Lever Safety, designed by prominent English bicycle-maker and businessman Henry Lawson.

Viewed today, it may appear strange — in part because of its 54-inch rear wheel, reflecting the belief at the time that speed called for big wheels — but in fact the Lawson Safety embodied many of the principles of today’s bicycle. To mount it, you climbed onto the seat between the two wheels, which made the bike easier to balance and also made headers less likely. The seat was low enough that you could reach the ground, and you steered the front wheel directly with the handlebars.

The oddity was that you “pedalled” this bicycle by pushing down levers on either side of the front wheel. While strange, this arrangement showed an awareness of the need to separate the power train from the steering, and to apply power to the back wheel rather than the front.

Rudge Safety, circa 1887.

1887 Rudge Safety

Between 1885 and 1890, dozens of manufacturers produced bicycles like this Rudge Safety of 1887. These machines were known as “crossframes,” a word that referred to the straight backbone that ran from the steering tube to the rear hub, crossed at right angles by the seat tube extending down to the crank bracket.

Other than the frame, this safety looks like a modern bike. It has two 28 inch wheels and rear wheel chain drive. The front forks, though hinged, are steered directly through the handle bars. It’s low to the ground, easy to balance, and hard to take a header over the handle bars.

One problem with this design was the overly-sensitive steering, caused by the short wheel base. Indeed, the wheels are so close together that the seat tube had to be curved to go around the back wheel. Another problem was the very rough ride caused by the small wheels with their solid rubber tires.

Starley Rover, circa 1888.

1888 Starley Rover

Designed by J.K. Starley, a nephew of the famous James Starley, this Rover model is one of the most important bicycles ever made. It is widely regarded as the first truly modern bicycle: a machine that was so successful in the marketplace that it brought an end to the decades-long debate about what a bicycle should be.

What made the Rover so significant? Ultimately, it didn’t incorporate any strikingly new technologies. It had two wheels of almost the same size, solid rubber tires and a spoon brake. The 30-inch rear wheel was driven by a chain, and the front wheel was steered through the handlebars. All of these things had been seen before.

What was new was the “diamond frame,” named for the shape made by the tubes stretching from the handlebars to the seat, from the seat to the rear hub, from the hub to the cranks, and from the cranks back up to the handlebars. Compared to a present-day frame, the only thing missing was a seat tube between the saddle and the cranks.

Men could ride this bicycle. Women could ride it. Kids could ride it. It was easy to balance, and it was also fast, setting records in 1886 that were beyond those of the tallest Ordinaries. The major difference between the Rover and today’s bike was the rough ride it gave, which came from its relatively small wheels and hard rubber tires.

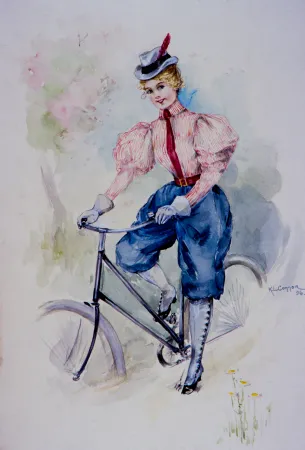

The diamond frame safety bicycle equipped with pneumatic tires made it possible for more people than ever to go cycling. The drop- frame version made it easier to ride for women with voluminous skirts, especially with skirt netting on the over the back wheel.

Massey Harris Model 6, circa 1898.

1898 Massey Harris Model 6

This Massey Harris Model 6 features all the elements of the Safety Bicycle as it matured in the later 1890s. The bicycle had two wheels of the same size, direct front steering and a straight seat tube to complete the diamond frame. It was very light, and its pneumatic tires offered a pleasant, vibration-free ride.

But there’s a twist. The Model 6 featured an enclosed shaft drive. You pedalled the cranks just as you would any would any other Safety, but the cranks turned a bevel gear instead of chain. The gear turned a shaft that turned more bevel gears at the rear hub, and this drove your wheel.

Gendron Safety, circa 1900.

1900 Gendron Safety

This Gendron Safety Bicycle reflects almost every aspect of the cycling experience that was related to the diamond frame Safety Bicycle by 1900. You rode this bike just as you would today’s single-speed bicycle: by grabbing the handlebars with both hands, putting one foot on the left pedal and pushing off with the other until you gained enough momentum to swing your right leg over the saddle. Once in the seat, you steered the front wheel directly through the forks, and powered the back wheel using pedals and a chain drive.

With a large gear at the front and a small gear at the back, you could make good speed. With pneumatic tires on both wheels, your ride was quite smooth. Thanks to its Hercules "coaster brake" hub, you could coast without the pedals turning and brake by jamming the pedals backwards.

But even on a seemingly standard Safety Bicycle there could be a twist. On the Gendron it was its wooden rims. Wooden rims were often favoured by North American manufacturers because they were light, strong, and cheap to make. Far from outdated, they represented the continuing search for improvements to the riding experience that played such an important role in the evolution of the bicycle in the nineteenth century.

This text is adapted from the 2015 Google Arts and Culture virtual exhibit, Cycling: The Evolution of an Experience, 1818-1900.