A ride through the evolution of the bicycle

With the happy arrival of spring, bikes are being dusted off and brought out of hiding for the new season. In honour of Bike Month (May 27-June 30), the Ingenium Channel is pleased to share a short series on the history of the bicycle, as supported by Ingenium’s beautiful collection.

Today, cycling is a part of daily life for millions of people around the world. Most ride on two wheels with air-filled tires, using handlebars to steer the front wheel and pedals to power the back wheel through a chain drive.

But it was not always so. The experience we take for granted today is actually the result of decades of innovation and development that took place in the nineteenth century.

Using the collections of the Canada Science and Technology Museum, we can look back at some of these innovations. Today, we look at part one of the three-part series.

PART 1: The Early Days of the Ride (1818–1860)

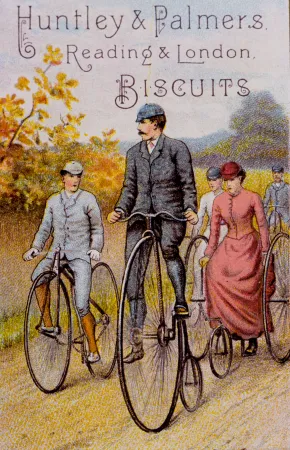

The early years of cycling saw the establishment of two ideas. One was the very idea of riding on two wheels, which took the form of the foot-powered Hobby Horse. The other was the idea of using machinery to make the application of human energy to cycling more efficient, as embodied in crank-powered Tricycles and Quadricycles. Throughout this period, cycling was an experience almost entirely reserved for the upper classes of society, and almost entirely limited to men.

Two men crash their Hobby Horses into a stream, illustrating the lack of control at high speeds, and also the lack of brakes.

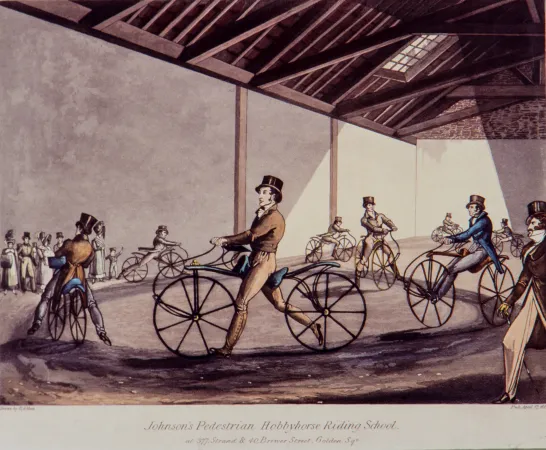

This Hobby Horse bicycle from Ingenium’s collection is thought to have been made by Denis Johnson of London, England, who was primarily responsible for introducing the Hobby Horse to Britain.

1818 Johnson Hobby Horse

The notion of riding on two wheels became popular after a fad started in Paris in 1818 following the demonstration of the Draisienne, which was invented by Baron Karl von Drais of Germany.

The fad quickly spread among France’s upper classes and then to high society in Britain and the United States, where the machine became known as the Hobby Horse or Dandy Horse.

To ride the Hobby Horse, you first adjusted the seat to a comfortable height and then swung your leg over the frame. Leaning forwards, you placed your forearms and chest on the rest, grabbed the ball on the end of the steering tiller and then pushed off from the ground with the tips of your feet. Though somewhat awkward, a good rider could reach speeds as high as eight or nine miles an hour.

The Dandy Charger, picturing a well-to-do gentleman riding his Hobby Horse. Printed in 1819 by John Hudson.

Muddy, uneven roads could be tough to navigate, and climbing hills was arduous. Coasting downhill was dangerous because you had no brakes, and every bump was transmitted to your backbone via the machine’s iron tires, stiff wooden spokes, and rigid frame. For these reasons, the Hobby Horse was usually ridden on flat ground in parks or, for those who could afford it, in special riding academies. For the most part, it provided a social ride for the well-to-do.

Interest in the Hobby Horse faded rapidly after 1820. Over the next few decades, designers explored various mechanisms for making the human energy applied to wheeled vehicles more efficient. However, they weren’t entirely convinced that people would be able to pedal a machine and balance on two wheels at the same time. This complex quadricycle in our collection shows off some of these innovations.

Willard Sawyer’s 1852 four-wheeled wooden Quadricycle, circa 1852.

1852 Sawyer Quadricycle

To ride the machine, you climbed in between the two wheels, sat on the seat, put your feet in the stirrups of the treadles below and then pushed forwards with one foot and then the other, in a motion similar to cross-country skiing. To steer, you twisted the T-shaped handle in front of the seat. While treadles and cranks were more efficient than pushing against the ground with the feet, the weight of the Quadricycle limited this riding experience to flat ground and a dignified pace.

In part two of this series, we will look at the next wave of bicycle designs: the Velocipede, Ordinary, and Tricycle.

This text is adapted from the 2015 Google Arts and Culture virtual exhibit, Cycling: The Evolution of an Experience, 1818-1900.