Current location:

Canada Science and Technology Museum

Provenance:

The Museum purchased the nocturnal from a scientific instrument dealer in Massachusetts.

Technical history:

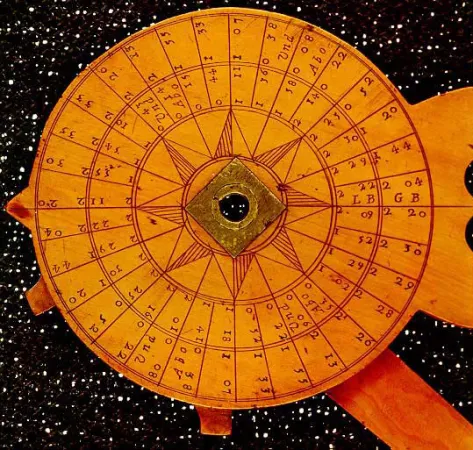

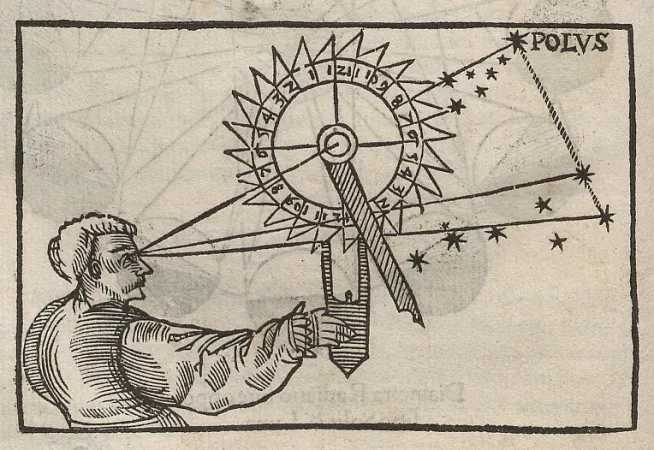

Mariners used nocturnals to determine local time at night by measuring the position of stars in the Big or Little Dippers. The most important reason that they needed to know the time was to determine the timing of high and low tides. Until the late eighteenth century and the invention of the marine chronometer, there were no clocks that could function reliably at sea and so mariners turned to the heavens to estimate time. They used the astrolabe or Davis quadrant to take daytime readings, and the nocturnal for readings after dark. Neither device worked when the skies were obscured by cloud or fog.

This device was built for the northern hemisphere: its markings show that it was designed to be used with Polaris, the North Star, as a reference point.

This nocturnal is of English origin but is unsigned and its maker is unknown. Based on the scales on the reverse side of the instrument, it was probably made between 1645 and 1695. English makers who built similar instruments during this period include Elias Allen, Fisher Combes, Thomas Copper, John Johnson, William Stone, Henry Sutton, Charles Turner, and Robert Yeff.

History:

During the great age of transoceanic exploration in the sixteenth century, mariners turned to astronomical observation to find their way across the featureless oceans. Instrument makers created numerous devices that mariners could use to measure their position and establish local time with reference to celestial bodies. As the European nations competed to explore, colonize, and exploit the riches of the New World, the demand for better navigational tools increased, prompting inventive craftsmen and scientists to produce many different devices.

First defined and explained by Michel Coignet in 1581, the nocturnal was specifically intended to establish local time at night, when the more common astrolabe was of limited use. This specific application made the device popular throughout the seventeenth century. But by the eighteenth century, it had largely fallen out of use since, by this time, instrument makers like John Hadley and Thomas Godfrey had introduced the much more accurate octant, which worked equally well in daylight and at night. Their early disappearance from the maritime world and the fact that they were often made of wood, mean that nocturnals are quite rare today.

- View all the collection highlights at the Canada Science and Technology Museum

- View other collection highlights related to Space, Mathematics