Making the universe sing

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

Bryson Masse

Algonquin College Journalism Program

Have you ever thought about how scientists figure out with such detail what happens, even at the smallest of scales? No microscope has ever been able to resolve the interactions at the atomic level and scientists can’t even see the invisible lines of energy and magnetism. How did we reveal the structure and patterns of condensed materials like liquids, crystals and proteins? This was made possible with the help of Alberta native Bertram Neville Brockhouse, inventor of the triple axis spectrometer.

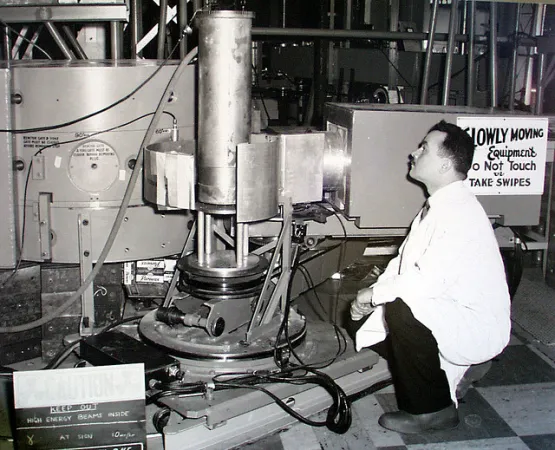

The spectrometer uses a beam of charge-less neutrons shot through the material to be analyzed. When one of those neutrons affects an atomic nucleus it resonates and vibrates in a very specific way. Neutrons are perfect probes as they permeate deep into the materials. Much like a bow striking a violin string, the note produced can uncover details about the matter’s characteristics. Brockhouse credits his early interest in electronic technology to an older cousin. During the great depression, he repaired radio equipment in Chicago and continued this when he moved to Vancouver. World War II started he joined the Royal Canadian Navy, servicing sonar equipment and spending months at sea. Using his education bursary after being discharged, Brockhouse chose physics as his field of study and never looked back.

In 1961, the physicist knew Ontario’s Chalk River nuclear research reactor as home where he investigated neutron spectroscopy. Working in heyday of particle physics, Brockhouse pioneered neutron scattering and brought insight to how matter is arranged and moves at the most fundamental level. His invention of the triple axis spectrometer allowed for the progression of particle physics, and our understanding of the universe would be incomplete without them.

Brockhouse later took a post at McMaster University, choosing the quiet Hamilton area to raise his children rather than the hectic life in Montreal or Toronto. Brockhouse worked as a professor until his retirement. His research got its due with the 1994 Nobel Prize in Physics. With almost 50 years between the investigation and award, it’s generally considered one of the longest gaps in Nobel history.

Bertram Neville Brockhouse was inducted into the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame in 1998.