Reading Expedition Photographs in the Frank T. Davies Fonds

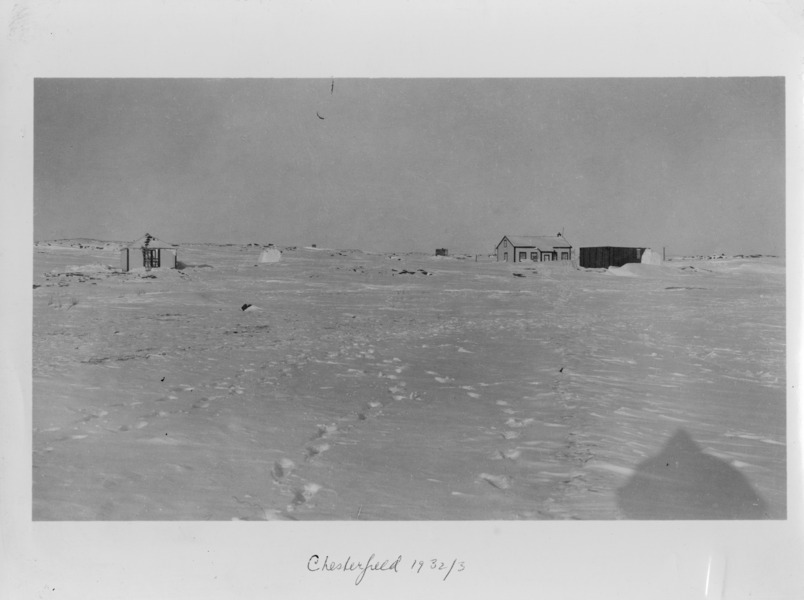

Frank T. Davies was a Welsh physicist who studied at the University of Saskatchewan and McGill University before joining the Byrd Antarctic Expedition in 1928. From this experience, Davies went on to participate in the Canadian Second International Polar Year of 1932-1933 in which Davies, Balfour Currie, Stuart McVeigh, and John Rae lived in Igluligaarjuk, Nunavut (then referred to as Chesterfield Inlet of the Northwest Territories) for a year to study the environment.

The Davies fonds, acquired by Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation in 2012, consists of detailed records that span the length of Davies’ forty-year career, from young physicist to his time leading the Defence Research Telecommunications Establishment. The collection is vast and varied, with photographs, notebooks, articles, correspondences with colleagues, written notes and memories shared by his children, and journals detailing everyday life during the expeditions he participated in. One journal dates from 1932-1933, written during the Second International Polar Year. This journal offers a glimpse of everyday life for the members of the expedition as well as insight on the interpersonal dynamics between the Inuit inhabitants of Igluligaarjuk and the settlers who included the RCMP and missionaries from the Roman Catholic and Anglican Churches.

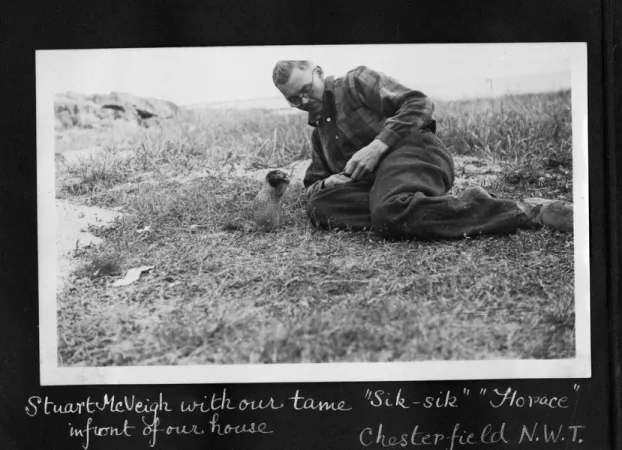

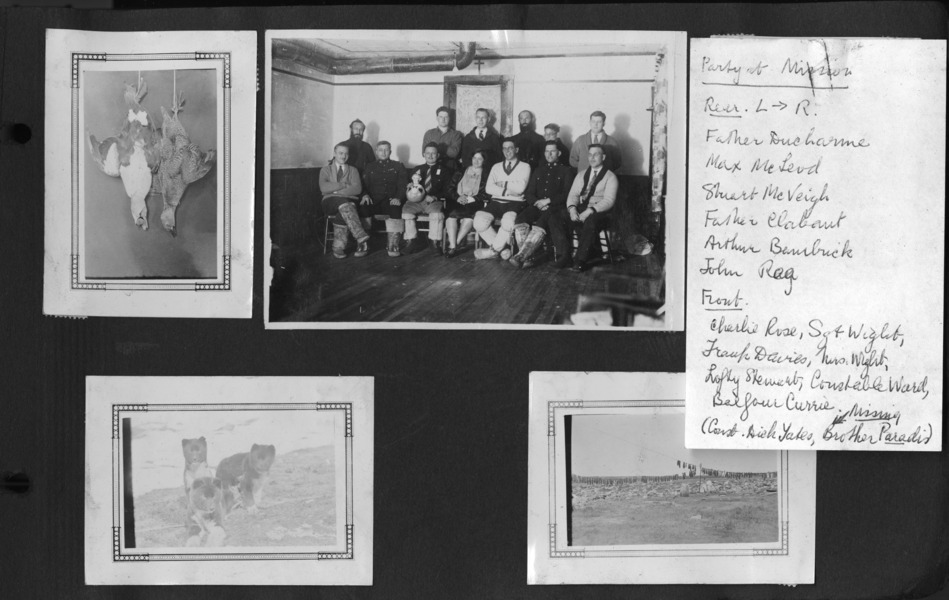

A page from Davies' Second International Polar Year album.

Problematizing Photographic Records

Photography played an important role in the data collection of the Second International Polar Year. Many scholars have drawn attention to the challenges of representing photographic historical records. In her essay In the Archival Garden, Joan Schwartz (2011) offers a pointed examination of a single historical photograph. Schwartz’s research highlights the importance of determining the function of photographic records, while Ricardo Punzalan (2014) considers archival diasporas through studying photographs from the collection of ethnographer Dean C. Worcester and tracing their dispersion across ten different repositories. This type of photographic dispersion is further complicated by lack of information around the creation of photographs, especially considering the possibility that such records may have been obtained without the consent of the people depicted. In their slow archives methodology, Christen and Anderson (2019) emphasize how centring a multiplicity of perspectives across time within historical records can offer a richer version of history that is continually in flux. With the perspectives of Schwartz, Punzalan, Christen, and Anderson in mind, I approached the Davies fonds with criticality and care, aiming for the slow methodology that Christen and Anderson forefront as necessary towards dismantling the colonialist roots of many historical records.

The shadow of the photographer is visible in this photograph.

Dispersion of photographic records

Prior to my visit to the Ingenium archive, I decided that part of my goal would be to find out who took the photographs in these records. It can be challenging to determine who actually took photographs held within historical collections since cameras were viewed as objective tools of observation, and even records linked to a single creator could have camera operators not named within the collection (Punzalan, 2014, p. 338). Cameras can carry the biases of their operators and Schwartz (2011) suggests that determining the creator of photographic records "connects the material evidence to a historically-situated observer, and raises issues of authorship, authority, and audience." (p. 75)

I started my search by looking through all the photographs in the Davies fonds related to the Second International Polar Year. There were multiple folders with a number of pictures, many with brief captions, many without. I paid attention to any markers of time within the photographs, the seasons, the snow on the ground, the flowers held by a woman sitting for a photograph. I looked for photographs of people photographing, knowing there was a possibility that multiple cameras were being used. After some digging, I found some answers regarding the creator of the expedition photographs in Davies’ Second International Polar Year diary.

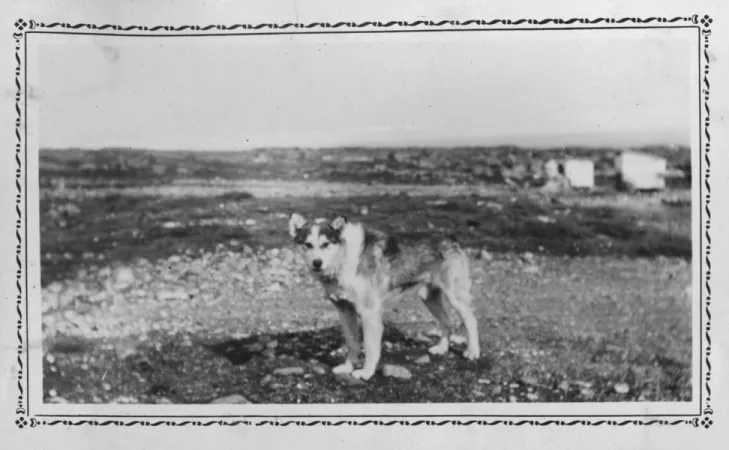

Davies was evidently a diligent note taker, offering a detailed look on his time in Igluligaarjuk. There are multiple references to photographs taken during the expedition and I found that Davies may have taken many of the photographs himself. Some examples of entries include: “took photo on Johnny’s roll before the police were up. Took several of Padlei,” dated August 14, and “took a shot looking at inner harbour,” dated August 30. With context from an earlier entry, I learned that Padlei is one of several local dogs. These notes correspond directly to photographs found in the album held within the Davies fonds. There are also mentions of Currie and McVeigh photographing, so I was able to surmise that all members of the expedition residing in the Igluligaarjuk area were regularly contributing to the collection of photographs within the Second International Polar Year records.

Image gallery

The Ingenium description for the Davies fonds contains information about other Canadian repositories that hold some of Davies’ records. This detail helps curtail the muddied historical context typical with dispersed photographic collections. A simple Google search related to the Second International Polar Year and the University of Saskatchewan archives (a repository I was directed to through the Ingenium description) led me to an archived digital collection of material related to the expedition. Here I found additional context that I had missed while studying the Davies fonds at the Ingenium archives.

Photo of McVeigh with the Arctic Ground Squirrel.

One of these details was an anecdote quoted from one of Davies’ logs in which he describes how McVeigh befriended an Arctic ground squirrel by feeding his nut rations to it. A closer read on this detail can offer insight on the timing of these photographs. Since the Arctic ground squirrel hibernates for part of the year, it is likely that this photograph was taken some time between May and September 1933. If the photographs within the Second International Polar Year album held at Ingenium are presented in chronological order, it may be possible to achieve an even closer read of the contents the photographic records alongside the dated journal entries.

There was another crucial detail included in the University of Saskatchewan Second Polar Year Expedition online collection. While the majority of the Inuit people pictured within these photographs are unidentified, both within the Davies fonds at Ingenium and the digitized collection at the University of Saskatchewan, there is one Inuit man, Singatuk, identified in the University of Saskatchewan digital collection. This cross institutional information now presents the possibility for Singatuk to be identified within photographs in the Davies fonds held in the Ingenium collection.

Multiple narratives

Davies’ descriptions of the Inuit people are what one would expect of a European settler in the 1930s. He disparages their way of life, frequently refers to the Inuit as primitive and asserts his support for their assimilation to European societal standards. The passages in Davies’ journal on the Inuit people offer another side of Davies than what is typically found within his biographical information. While it is evident that Davies was an accomplished scientist, it is nonetheless important to identify his biases as a researcher on this expedition, and also as a researcher photographing the Inuit people he encountered during his time in Igluligaarjuk. As mentioned above, the majority of the Inuit people pictured in the expedition photographs are not identified and this silence speaks to the biases of the settlers who formed the expedition team.

In records written by Davies’ daughter, dated from 2012, she describes Davies as a progressive figure who was anti-colonialist. While it would be simple to dismiss this as someone describing an idealized version of their father, it is important to acknowledge that these narratives exist side by side. They do not necessarily negate one another but rather enrich each other, adding to a tapestry of historical nuance that is afforded to the reader by the details held within this collection. It bears repeating that despite their breadth, the records on the Second Polar Year within the Davies fonds lack Indigenous perspectives. This absence demonstrates whose history has been preserved over the ninety years since these records were created.

Opportunities for Further Exploration

There is also great potential for additional historical context to be gleaned from the records I could not cover in the scope of my visit to the Ingenium archive. Even within Davies’ journal on the Second International Polar Year expedition, there is much more information on life in Igluligaarjuk during that period, some of which describes harms perpetrated by settlers and missionaries on the Inuit people. There is the potential for records such as these to act as evidence for colonial harms that can push back against attempts to whitewash history.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!