An engagement nearly cuts a scientist’s career short

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

Molly Gatt

Algonquin College Journalism Program

Harriet Brooks Pitcher, an esteemed nuclear physicist, was the first woman to receive a master’s degree from McGill University. And while studying at McGill, Pitcher worked with Ernest Rutherford, the father of nuclear physics.

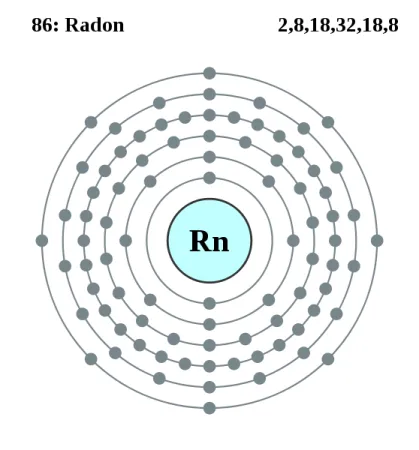

She investigated radium and discovered that over time it became radon – an uncommon radioactive gas – which would in turn, change as well. This process was called transmutation of the elements, and the discovery helped build a greater understanding of the atom and nuclear energy. Pitcher’s research inspired Rutherford’s work, contributing to his winning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Shortly after graduating McGill, Pitcher began working as a tutor at Barnard University in New York City. But when she became engaged in 1906, she was told she would not be allowed to continue working once she was married. Rather than giving in, Pitcher made the case that women should have the right to continue their work after getting married and having children. But the university stood its ground. Eventually Pitcher broke off her engagement and resigned her position. She traveled to Paris to work with Marie Curie, another famous physicist.

Pitcher’s career only lasted 13 years, as shortly after she started working with Curie, she wed Frank Pitcher and gave up science for good. She died in 1933 at the age of 56 – likely from handling radioactive materials – as scientists at that time did not use any protective gear. She was inducted into the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame in 2002.