Why we collect

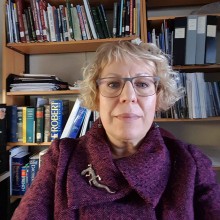

As Ingenium prepares to move the national science and technology collection into the new Collections Conservation Centre over the coming months, curator Sharon Babaian reflects on the purpose of collecting.

As curators, we collect objects to document, preserve, and understand the past. The things made and used by people are physical evidence of human invention, activity, and need; they also reflect the societies, communities, and cultures that created and adopted them. At Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation, we collect the material evidence of science and technology in all its forms.

Consider this marine sextant, made by Jesse Ramsden.

This artifact represents scientific research transformed by a gifted instrument maker into a practical, durable tool for marine navigation. Mariners used sextants to establish their position at sea, by measuring the angles of celestial bodies like the stars and the moon.

Ramsden was an eighteenth-century mathematician who developed a method for mechanically dividing the circle into a precise scale which could be consistently replicated. This allowed instrument makers to produce smaller, more accurate devices, offering users a distinct advantage in ensuring safe and efficient navigation. This sextant is also a potent symbol of Britain’s maritime power — the foundation of its political and economic domination over large parts of the world.

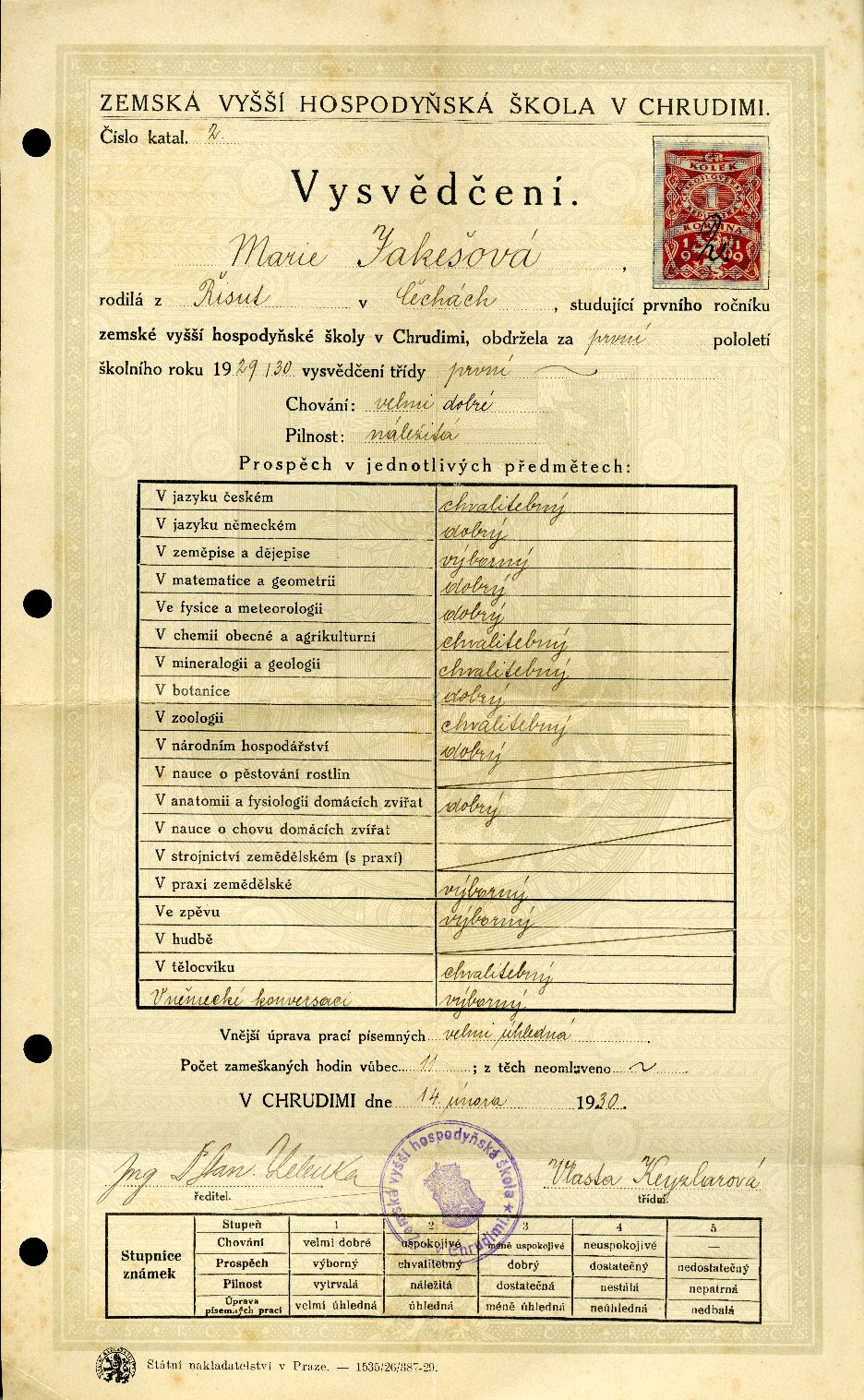

Marie Pick's (nee Jakesova) son translated the contents of this report card, so that researchers would have a sense of who she was before her marriage and immigration to Canada.

Some of the objects we collect can seem very ordinary. Yet a simple piece of paper, like this school report card, contains meanings far beyond the words on the page.

This document tells us that Marie Jakesova graduated from agricultural school in the Czechoslovak Republic in 1930. The courses she took tell us that, in a farming region like Chrudimi, agricultural subjects were considered important areas of study, even for young women. The timing of Marie’s graduation — during the Depression and with war looming — also hints at why she and her family emigrated to Canada in 1938.

That Marie preserved this piece of paper so carefully reflects the special importance it held for her, perhaps because it marked the beginning of a lifelong interest in agriculture. After her husband Otto established a seed company in 1947, she took a leading role in running the business. After her husband’s death in 1959, Marie, together with her sons, helped to build what became the largest forage and turf seed company in Canada — the Pickseed Group of Companies.

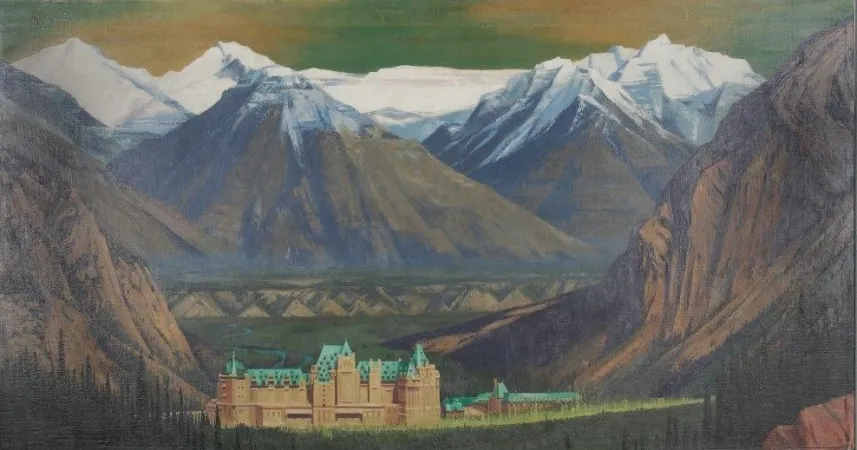

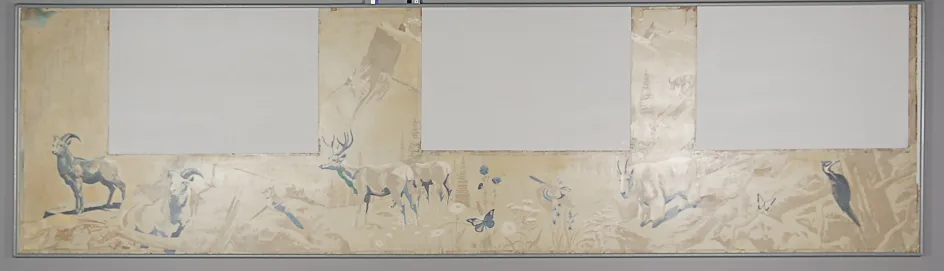

Other objects we have collected may seem entirely out of place in a science and technology museum. These paintings of Banff National Park by Charles Comfort are not just beautiful works of art. They represent the last great era of passenger rail travel in Canada; they highlight how a wilderness once considered an obstacle to development became a valuable resource to exploit. In the mid-1950s, the Canadian Pacific Railway updated and upgraded their passenger service to compete with air and automobile travel. They ordered 18 dome-observation cars, one of which travelled at the end of each transcontinental train. They named each car after a park along the route. To decorate the lounges, they commissioned famous Canadian artists including A.Y. Jackson, A.J. Casson, Edwin Holgate, and Charles Comfort to paint murals of each park. Each car had a main mural and “a vague continuation” of the image that covered the adjacent side wall and fitted around the windows. These paintings were one important component of the railway’s plan to promote travel, by presenting “to world travellers the scenic and touristic beauty” of the Canadian landscape.

Every object we collect has a direct link to the history of science and technology. However, an artifact’s significance often reaches far beyond that obvious relationship to embrace all aspects of life in Canada. Each artifact tells us remarkable things about the world we’ve made and the things we value. This helps us to view the past in new ways, while shedding much-needed light on the place of science and technology in our lives — today and tomorrow.