Bringing museums to life through performative storytelling

Today’s museums are facing a monumental challenge: in an increasingly loud world, how can we ensure that our important stories resonate with the next generation?

When I walk down the sidewalk, it scares me to see people — particularly youth — constantly distracted by their phones. I reserve judgement, however, since youth are truly not at fault. The next generation has never known a world that isn’t constantly clamouring for their attention, offering up endless entertainment in the form of Netflix, movies, video games, and apps galore.

As a museum educator at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, I believe it’s critically important to recapture the attention of youth, and the general public. I’m not alone; school teachers, parents, and all responsible citizens have a sense of pride in our national stories, along with an obligation to ensure they’re not lost amidst the noise.

But how can we make museums more alive? How can we refresh our stories — in museums and beyond? I believe the answer lies in performative storytelling.

Our love of stories (and storytelling) is a defining aspect of humanity since early times. Here at the museum, our interpretive guides can make any visit interesting by using stories of innovation. But our true stories are competing with brilliantly-written and beloved fictional personalities, such as Jon Snow or Walter White.

Perhaps then, it stands to reason that in order to share our rich (and historically accurate) stories, we need to adapt our competitors’ techniques. Our contenders’ stories are so provocative because of their ability to inspire familiarity and fun. We are all naturally obsessed to hear about similar instances happening to others, learning from them, and then telling others. Any museum surely aspires to achieve these goals… but how should we apply them to our own stories?

Performative storytelling is growing in popularity as an effective educational tool. Consider that the most popular way to interact with museum collections is by following a guided tour. It is only one step further to transform the guide’s immediate responses into a real “performance.”

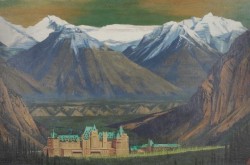

The Fortress of Louisbourg — a national, historic site on Cape Breton Island — provides a strong example of performance as a heritage strategy. The site is “intended to transport tourists into an authentic, three-dimensional, and multi-sensory past environment” of the 1700s. Most important to creating this illusion is that interpreters interact with others as if they are really from the past.[1]

The difficulty often associated with this move is that many people consider the acting in these situations to be “childish.” Some believe it turns their stories into fleeting, belittling fantasies, thereby robbing the ability to accurately communicate their factual information. However, the reality is that performance only gets this reputation from its ability to reintroduce youth to museums.

Performance not only captures our attention, but also allows us to more easily understand the world around us. This natural interest follows us all throughout our lives. We continually learn social behaviour watching others perform — how they act, the clothing they wear — whether they be elders or friends.

However, it is important to remember our goals when promoting these stories. The father of heritage interpretation, Freeman Tilden, shared that, as heritage institutions, “our job is to inspire [visitors]… to want to learn more.” Furthermore, he stated that, “… we cannot forget that people are mainly with us seeking enjoyment, not instruction.”[2]

As much as this is true, we must be equally careful not to introduce blind entertainment. Amusement is useful (as our competition wins public interest through inspiring fun), but we all have deeper messages to communicate. Still, institutions often fear that the performative fun of these messages will eclipse this deeper meaning.

A study that I led recently in Québec proved, however, that captivating performances actually encouraged the public to question more. The investigation revealed that visitors to heritage sites valued interpreters’ explanations, the ability to ask questions, and, importantly, the experience’s general fun. Similarly, when I presented this investigation’s educational merit to my university colleagues, I opened the presentation in character as James Wolfe, complete with tall, black boots (see photo). Using this technique profoundly seized my audience’s attention, perfectly demonstrating my point. To remain relevant when passing on our stories, we must enhance them by combining their messages with performative fun.

It would be foolish not to seize the effective tool that is performance to actively pass our important stories. By adding a performative element to these stories, we can inspire both familiarity and fun. Only then can we truly make our museums more alive.

[1] A. Gordon, Time travel: Tourism and the rise of the living history museum in mid-twentieth century Canada, Vancouver, UBC Press, 2016, p. 184-85.

[2] F. Tilden, Interpreting our heritage, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2007, p. 55.