Project Log #3: PHP and Databases

New week, new ideas.

In my last post about my adventures in building a weather station for the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, I explained how I got the sensors to read data (like temperature and humidity) and return it back to the Raspberry Pi. Unfortunately, this functionality is not yet at the point I want it. While I can see the data on a screen, I have no way of doing anything with it. I could only locally see the data in the Arduino serial monitor. The serial monitor is a display that shows data coming in via transmission from the Arduino to the Raspberry Pi. Naturally, the next thing to do would be creating a method to save the data as it comes in.

With my experience in the Python programming language, I felt it was ideal to use for this project. It turns out reading serial communication is a rather common thing throughout programming languages. That simplifies my job significantly. Using a resources I found online, along with my own knowledge of file writing in python, I made a simple program that would read data and add it to a simple text file.

Chunk of code that collects data and writes it to file. The entirety of the code is available at https://github.com/mebsim/WeatherStation.

But a text file is not useful when the ultimate goal is to have the data be available live via the internet. The best way to make the data available on the internet is to first store it in a database. There are a variety of methods to display the data from the database, so I want to start as basic as possible, in order to allow it for multiple uses.

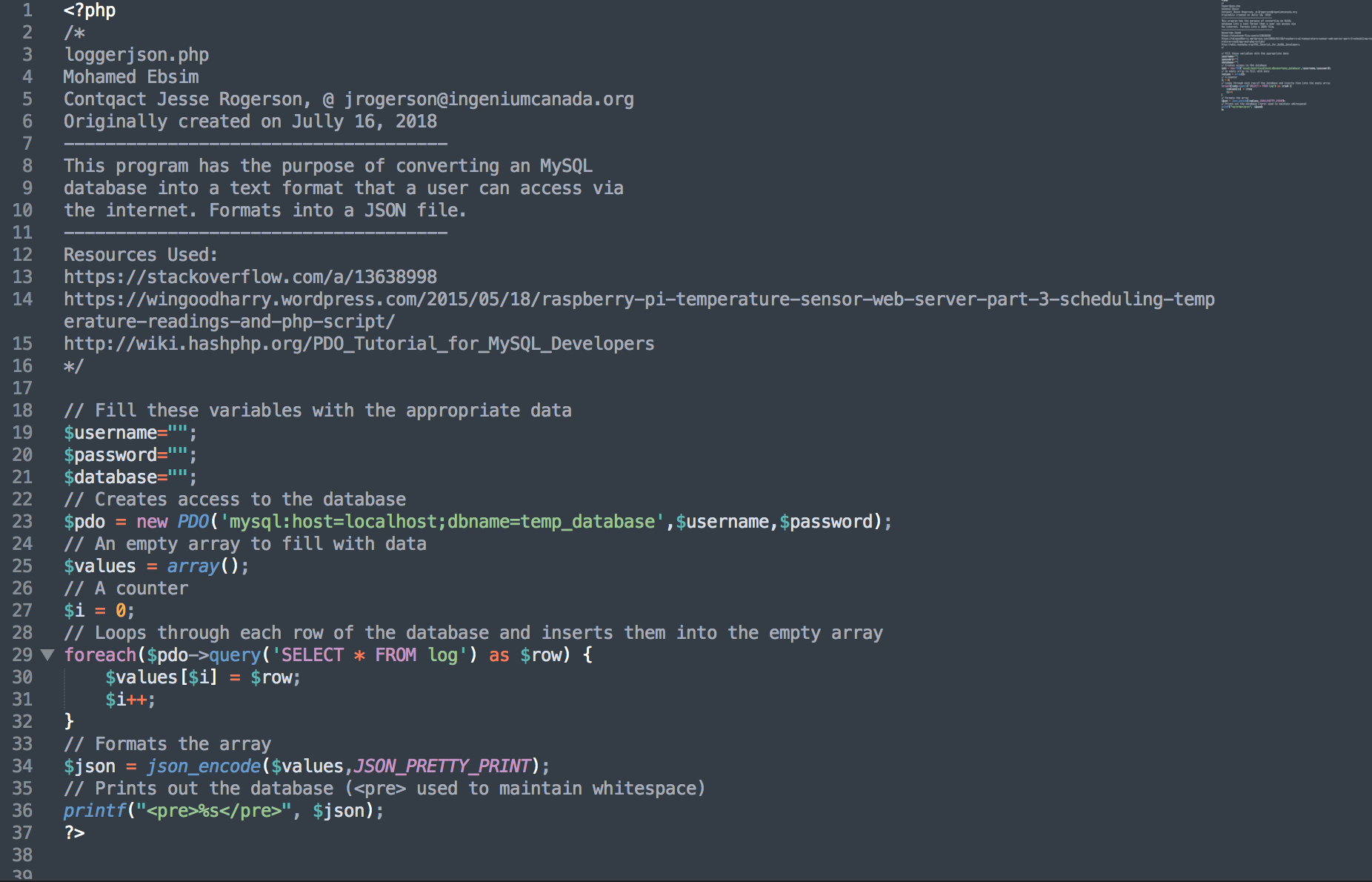

A popular thing in the Raspberry Pi community is to use it as a mini-server. Since it is a mini-computer and the model we have is Wi-fi enabled, it can be used in a variety of ways. What I decided to do was make an internal website (only accessible within the museum’s network) that displayed the data from a database on the Pi. After some research, it seemed that a mixture of MySQL and PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor (PHP)was the way to go. PHP is a form of scripting language that runs on a server. The other half, MySQL, is a very popular database management system.

I used this tutorial to figure out how to set it up, although there are plenty of them online. To sum up what is said in the tutorial, you go through and install the appropriate resources, do some light programing (see code below), and run the program. Just as a heads up; the tutorial used an outdated version of PHP to grab data from MySQL. In order to make it work, I had to update the PHP with the library PDO. I updated it using PDO with the help of this site.

Updated PHP code I wrote that would collect and display data from the database

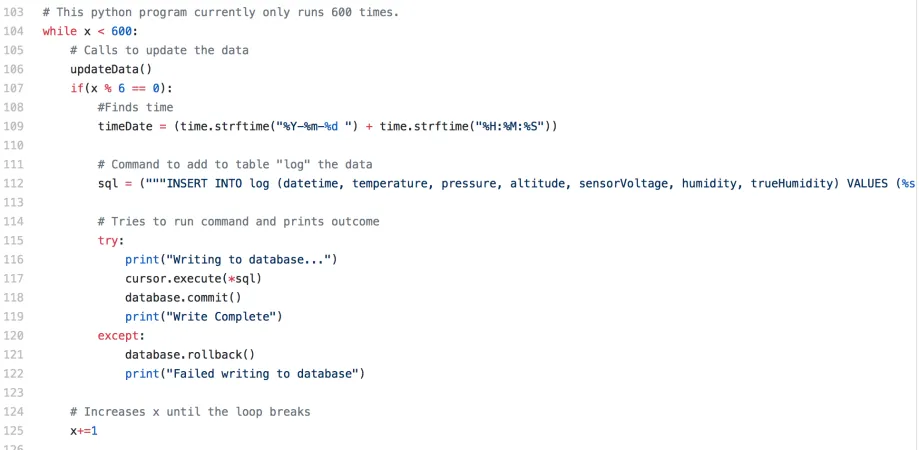

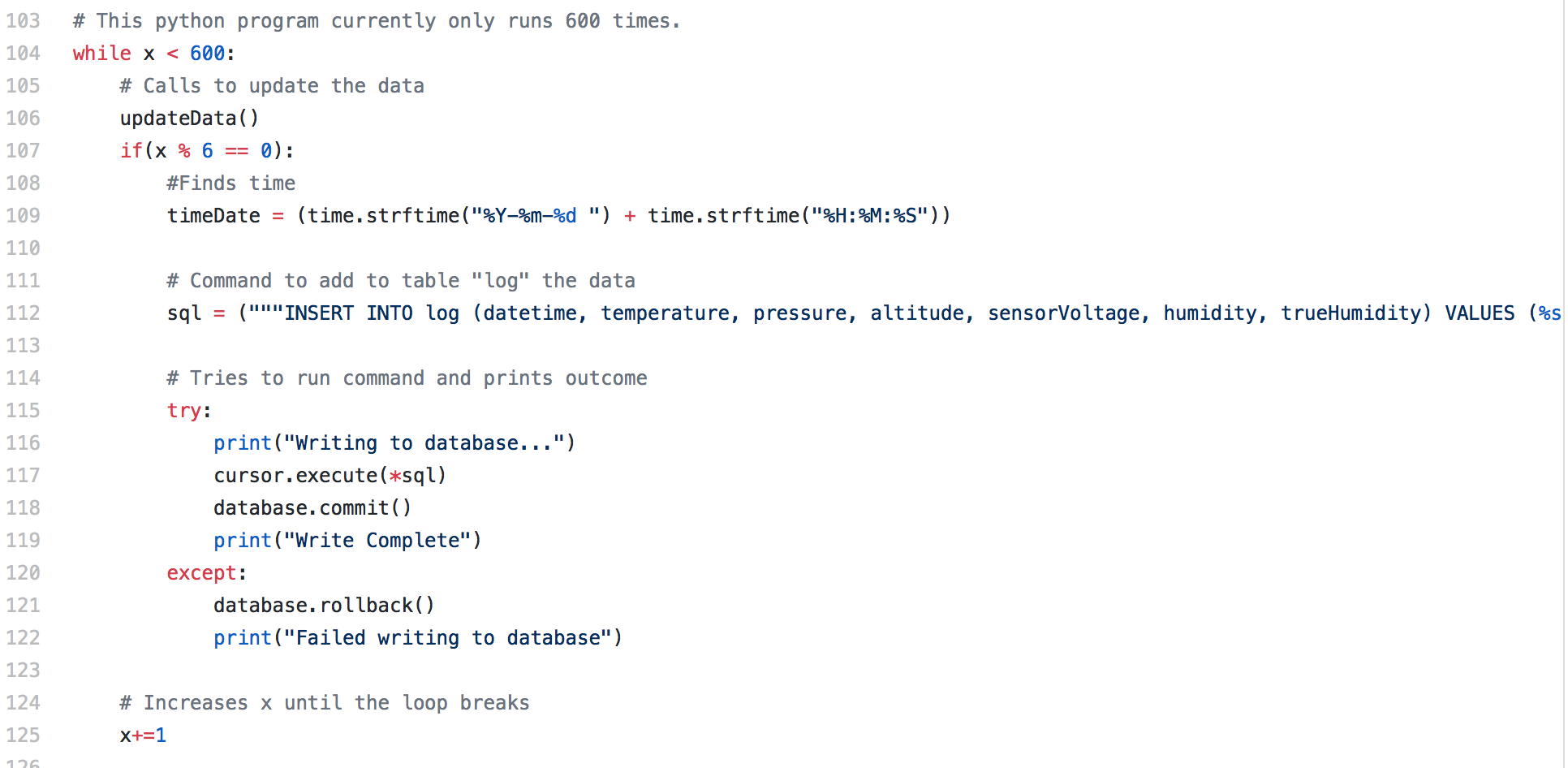

The final thing I had to do was update the code that saves the data, in order to change the saving location from a file to the database. The tutorial above also contained a method to access the database. I incorporated it into my own program, with some minor changes, since again the tutorial was slightly outdated.

Updated Python code that saves data to database. This was added to the Python code above.

This took a while, but at the end I had a small server showing the data to anyone who wanted to access it. It sets the foundation for future development.

As we get closer to the end of my time with the museum, there is going to be a larger movement from programming to physical design. Stay tuned to read about our next challenge!

All the code that has been made can be found at my GitHub page: https://github.com/mebsim/WeatherStation