NASA, eh? Reflecting on Canada’s contribution to Apollo 11

The story of how Canadian engineers from Avro went to work for NASA after the Arrow program was cancelled, and helped put a man on the moon.

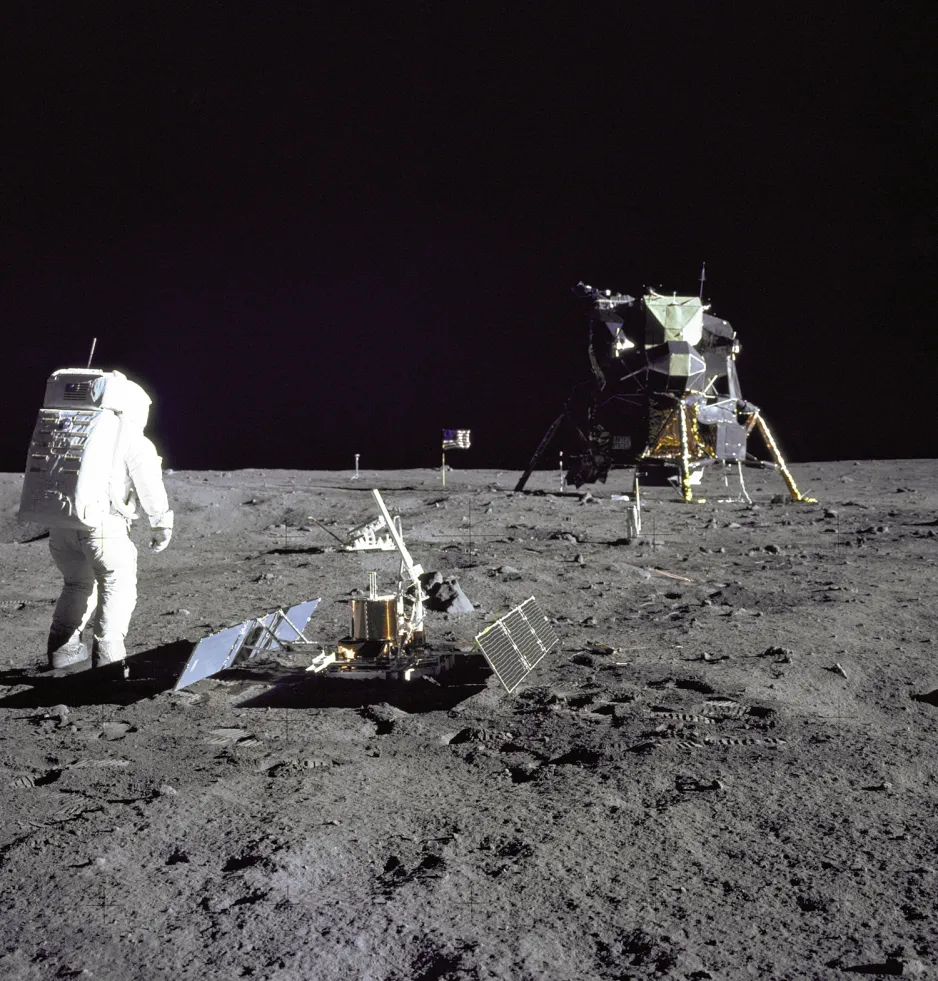

Saturday, July 20, 2019 marks the fiftieth anniversary of Apollo 11. While the focus is generally on Neil Armstrong — the first person to step foot on the surface of the Moon — or Buzz Aldrin, the media and others will sometimes mention the army of people who made those first steps possible.

Buzz Aldrin at Tranquility Base.

Few people are aware, however, that 12 of the 400,000 full-time NASA employees were not only born and raised in Canada, but fundamental to making the Moon landing a success. They were the Avro engineers who went to work for NASA after the Canadian government cancelled the CF-105 Avro Arrow. In Canada, they are best known as a collective, and their move to the U.S. is often lamented as the “Brain Drain.” Let’s take a closer look at how the Avro engineers came to work for NASA, and the contributions they made to the American Moonshot.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was born on October 1, 1958 as a successor of sorts to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). The new organization was to continue research in aeronautics and to explore peaceful applications for space science. One of its first major initiatives was not to put a man — and it really was only men considered at the time — on the Moon, but to put a man in space. The Soviets had already put an artificial satellite in orbit, as well as a few (unfortunate) animals. In the competitive spirit of the Cold War and the emerging Space Race, the Americans were behind and feeling anxious.

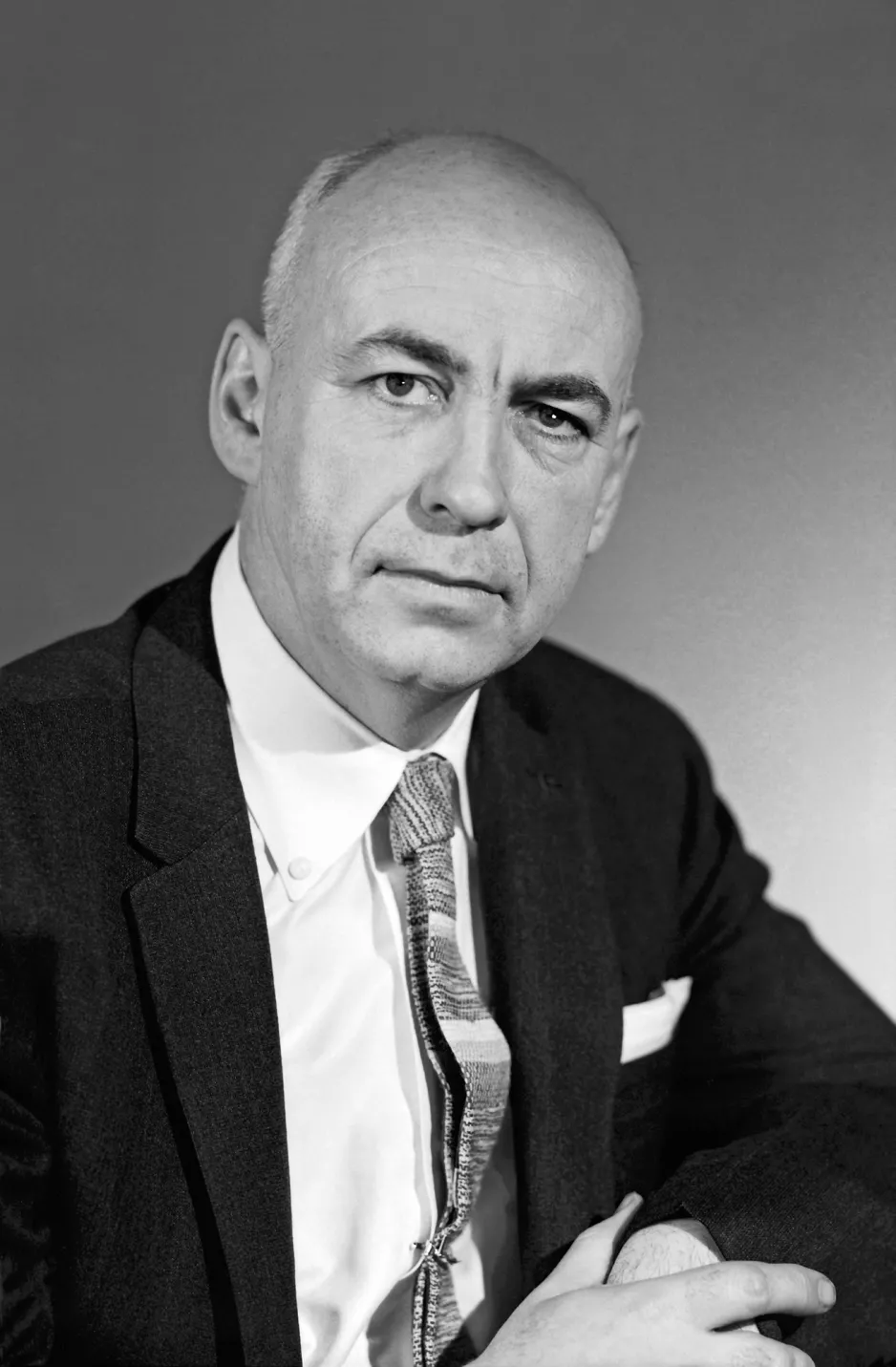

Bob Gilruth - 1959

A man named Robert (Bob) Gilruth was put in charge of the newly-formed Space Task Group (STG). In December 1958, the program to put a man in space was named Project Mercury. One month later, McDonnell Aircraft of St. Louis, Missouri, won the contract to build NASA’s first crewed spacecraft. Things were coming together but with only 150 engineers in its ranks by March 1959, the STG was desperate for the talent it needed to make it all happen.

Meanwhile in Canada, Avro Aircraft was still reeling from the cancellation of the Arrow on February 20, 1959. Chief Engineer Bob Lindley and Chief of Technical Design Jim Chamberlin were concerned about their “guys” and wanted to help them find meaningful work. While working on the Arrow, the two men had made good contacts at NACA, namely Bob Gilruth, and so they called him up to see if NASA might be interested in working with some engineers from Avro. Gilruth was very interested indeed, knowing the kind of cutting-edge work and technology that was used to design and build the Arrow.

Encouraged, Lindley and Chamberlin flew from Malton to Washington, D.C. armed with a proposal: Canada would lend engineers from Avro to NASA’s Project Mercury. There was interest at NASA, but others in American government were not as enthusiastic. Prime Minister John Diefenbaker was not on board either, because he was skeptical of space travel in general. All that said, there is no conclusive evidence of where exactly the proposal died.

Naturally, Lindley and Chamberlin were disappointed. As a last resort, they asked Gilruth if NASA would be interested in hiring some of the Avro engineers outright. The offer was appealing because the STG was having trouble attracting the talent it required to get Project Mercury off the ground (space pun!). Generally speaking, senior engineers in the U.S. did not want to take a risk on a program that could be dissolved in a couple of months, not to mention that salaries in the private sector were much better. Gilruth agreed to fly up to Malton with a few of his colleagues to conduct some interviews.

Lindley and Chamberlin called a meeting with the Avro engineers in the cafeteria at the Malton plant. They explained what Project Mercury was, and invited anyone who was interested to leave their resume for NASA’s consideration. In the end, NASA officials reviewed 400 applications and on March 14, 1959, conducted interviews with 100 candidates. Thirty-two job offers were made, and 25 were accepted. Of those 25, 12 were born and raised in Canada: Bruce Aikenhead, Richard Carley, Jim Chamberlin, Stanley Cohn, Eugene Duret, Bryan Erb, Stanley Galezowski, Fred Matthews, Owen Maynard, Leonard Packham, Robert Vale, and George Watts.

According to Gilruth, these men were a “God-send” to NASA. The Canadians worked on all aspects of not only Project Mercury, but also the Gemini and Apollo programs. Chamberlin became the Project Manager for Mercury and designer of the Gemini spacecraft. Chamberlin and Maynard were major advocates for Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (the proposal that the lander spacecraft would separate and then reunite with the Command module while it orbited the Moon). Maynard was also instrumental in the design of the lunar lander itself. Aikenhead became a flight simulation and training specialist. Erb designed the ablation shield of the Command Module, ensuring safe re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere. Carley lead the development of the guidance and navigation systems in Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. Matthews played a leading role in developing the Flight Controller handbook, and assisted in the development of the Mission Rules handbook. Packham worked on communications, tracking and radar systems in Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo.

This is just a small sample of the contributions Canadian engineers from Avro made to the American’s first moonshot. For Gilruth’s money, the cancellation of the Arrow was “a big break” for NASA. The guys from Avro were instrumental in what was arguably the greatest technological achievement of the twentieth century.