Apiarist Ambitions: Subscription Incentives in the Canadian Bee Journal

When the going gets tough, I get this vision: I’ll pick up my life, buy a plot of land in the countryside, and take up apiculture. That’s right: beekeeping.

In reality, however, I know nothing about beekeeping. Admittedly, my ‘vision’ is mostly a romantic delusion that I lean on when my research and writing stall. Browsing the Rare Books Room at the Canada Science and Technology Museum Library and Archives, I stumbled upon an extensive hive of periodicals on all things apiculture that might help with my apiarist ambitions. It’s a worthy distraction.

What I do know quite a bit about is the Victorian periodical press. I’m a doctoral candidate in History at McGill University and I study the ways ideas and information circulated between publications in nineteenth-century newspapers and magazines. However, that’s not necessarily important to this post. What is important is the museum’s impressive collection of periodicals on beekeeping and bee culture. The museum’s collection holds a range of Canadian and American periodicals related to apiculture, including titles like American Bee Keeper published in Falconer, New York, Gleanings in Bee Culture published in Medina, Ohio, Beekeepers Review, published in Flint, Michigan, and Canadian Horticulturalist & Beekeeper published in Toronto, Ontario. All these titles and more are available to the public for browsing or research.

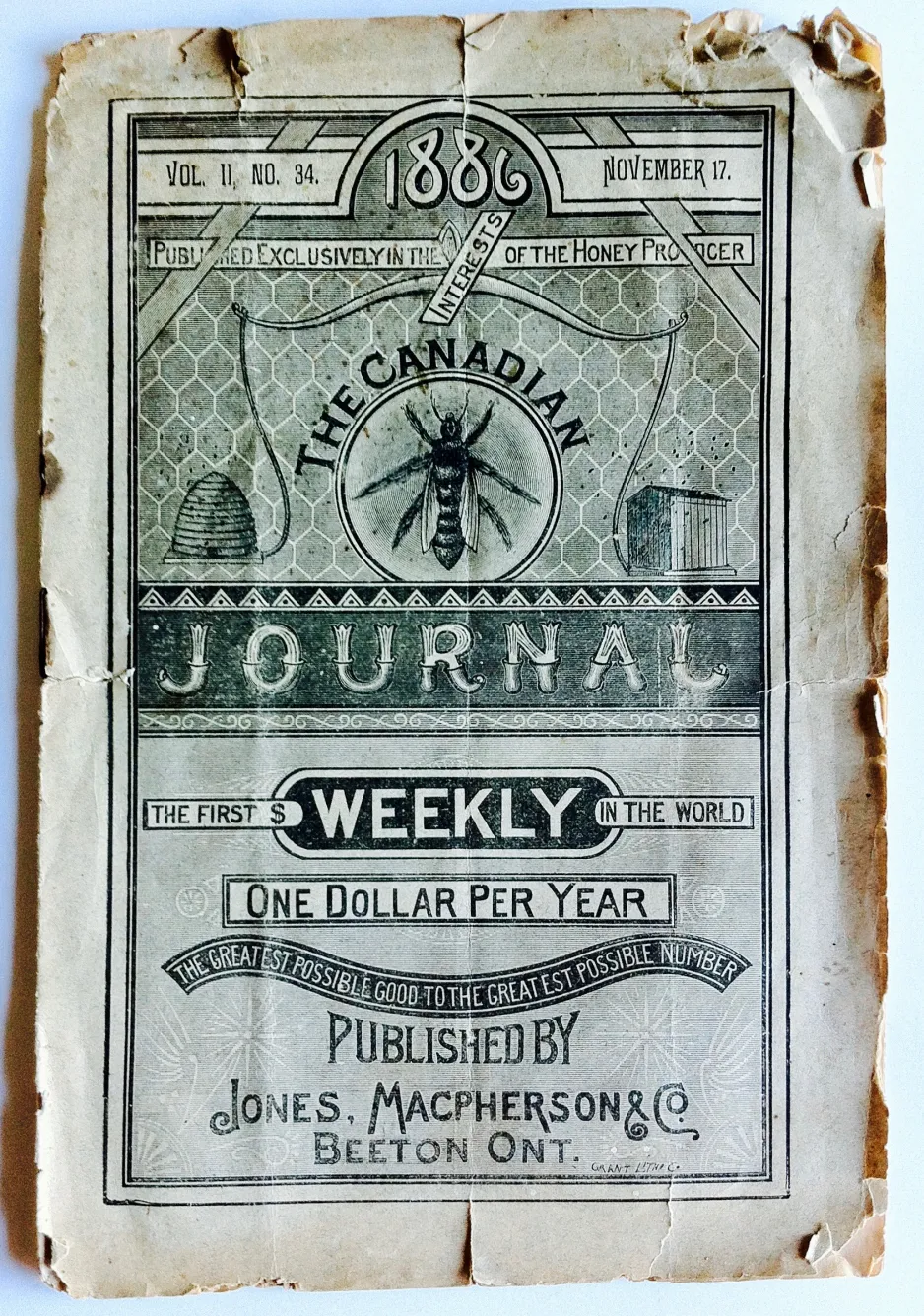

The Canadian Bee Journal 11.34 (November 17, 1886). Rare Books Collection. Canada Science and Technology Museum.

The graphic cover of the Canadian Bee Journal caught my eye. Its publisher, Jones, Macpherson & Co. in Beeton, Ontario (Yes, BEEton, now in the Town of New Tecumseth, about an hour and fifteen-minute drive north of Toronto), branded the weekly as “exclusively in the interests of the honey producer.” It sold at $1 for a year’s subscription. Part of the publishing team, David Allanson Jones (1836-1910), was the first commercial beekeeper and breeder in Canada. There is an Ontario Heritage Trust plaque honouring him in Beeton and the community was renamed from Clarksville in 1874 to celebrate his entrepreneurial success.

In examining Jones’ periodical, it’s striking that he didn’t bother to include the word “bee” on the cover; in its place, he substituted a wonderful engraving of the pollinating insect on a honeycomb background. The masthead is equally stunning and picturesque. Two beehives sit next to a forest with bees buzzing nearby. In the distance are neatly organized hives. A horse draws a buggy. Small buildings and a church dot the landscape. A motto printed underneath proclaims, “The greatest possible good to the greatest possible number.” It’s wholesome and it’s delightful.

Like many trade journals of the late-nineteenth century, the Canadian Bee Journal was collaborative with its subscribers in that it relied on readers to submit questions and commentary to fill its pages. In stating the periodical’s intent in the opening April 1885 issue, “The science of apiculture is yet in its infancy; great strides are being made every year, and the aim and object of The Canadian Bee Journal will be to further its progress in every possible and legitimate way.” [1] The journal reminded readers in each issue that “Communications on any subject of interest to the Beekeeping fraternity are always welcome and solicited.”

The November 17, 1886 issue, for example, opens with an article on apiary tools and technologies, detailing how to use wax extractors to separate impurities from beeswax. What follows are issues of law (in Walkerton a Mr. Harrison had 80 beehives causing “a great nuisance”), an article on beekeeping being difficult work (perhaps I should take note), tips from subscribers on wintering, and how to hire a pasture for bees. ‘Sundry Selections’ offered reader-driven questions and answers on the practical aspects of beekeeping. The weekly periodical also gave a list of bee colonies for sale, convention notices in Ontario and Michigan, and an account of honey markets across Ontario and beyond to Detroit, New York, and Chicago. Advertisements for labels, honey boxes, glass jars, and other equipment fill the back pages.

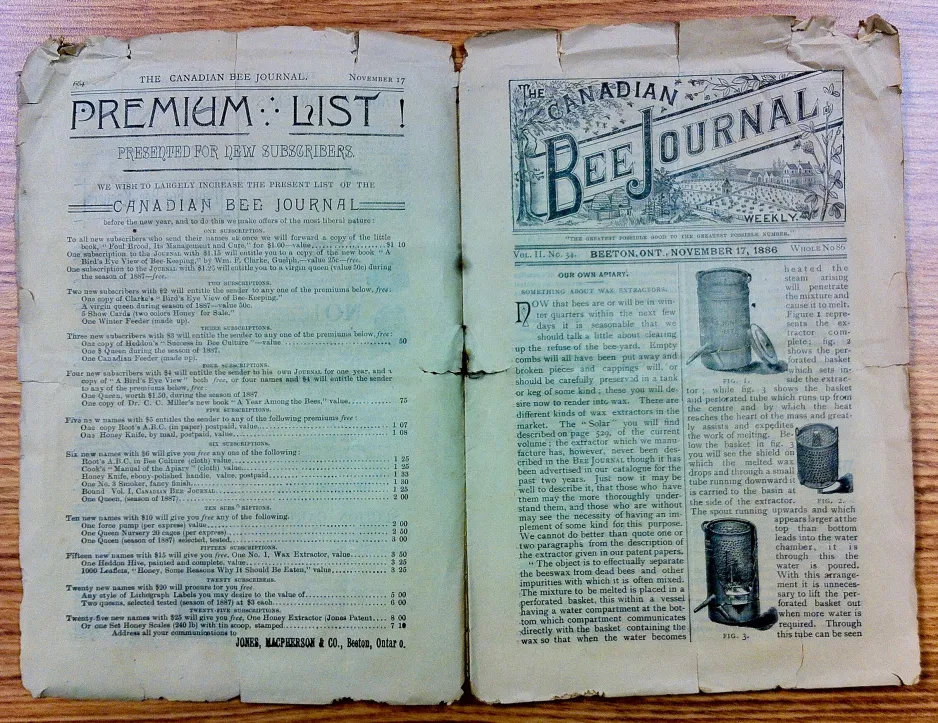

Detail of the masthead in The Canadian Bee Journal 11.34 (November 17, 1886), 665. Rare Books Collection. Canada Science and Technology Museum.

What I find most interesting in the Canadian Bee Journal is the way it used incentives to expand the periodical’s readership. The use of incentives, prizes, and contests to sell newspapers and periodicals was a common sales tactic in the Victorian period. In the United Kingdom, The Smoker (tobacco, not meats), offered life insurance policies where if the possessor of a current issue was killed in transit on a train, their next-of-kin would receive £1,000. Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday offered subscribers a variety of prizes ranging from silver pocket watches to the more questionable revolver. Tit-Bits, a periodical comprised of mostly clipped and reprinted texts offered cash prizes to subscribers. The press used all sorts of tactics to lure readers. The Canadian Bee Journal, however, offered a fresh approach.

In increments of 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 15, and 25, subscribers had the choice of ‘free’ literature and equipment to motivate buying multiple annual subscriptions. The more subscriptions a reader purchased, the better the incentive. First-time subscribers gained a copy of A Bird’s Eye View of Bee-Keeping and a “virgin queen bee” for the upcoming honey season. Two subscriptions gave the option of show cards or a winter feeder. Three subscriptions offered a choice of a queen bee, a Canadian feeder, or a copy of Success in Bee Culture. Five subscriptions and the apiarist would receive a honey knife but for six it would come with a polished-ebony handle. Other incentives included a painted and completed hive, a honey extractor, lithograph labels, 1000 leaflets of “Honey, Some Reasons Why It Should Be Eaten,” and a set of honey scales. The Canadian Bee Journal was not only motivated to sell subscriptions. These incentives had the additional purpose of expanding the practice of apiculture more generally in the region. [2]

The Canadian Bee Journal 11.34 (November 17, 1886), 664-665. Rare Books Collection. Canada Science and Technology Museum.

The motivation for expanding beekeeping and honey production was possibly tied to a potential export market in the United Kingdom. In the November 17, 1886 issue, the Canadian Bee Journal reprinted an article from the Canadian Gazette that discussed the Ontario Beekeepers’ Association’s recent meeting with British Beekeepers in London, United Kingdom. This sort of reprinting from other sources was common and as the editor gave full credit to the Canadian Gazette it was part of a ‘courtesy of the trade’ in reprinting texts. According to the article, the English dealers spoke “in high terms of the quality of the honey” while judges deemed Canadian honey “to be superior in texture, color and flavor, to ordinary English honey.” The article goes on to explain how Canadian honey was selling especially well on the English market. The Gazette wrote, “The intention is to endeavour to build up a large and prosperous honey trade here both of Canadian and British honey, while exercising the greatest care with those who handle it to prevent its adulteration.” [3]

The November 3, 1886 issue noted that at an exhibition in South-Kensington, London, Canadian honey outdid their American neighbours. Middlemen – not the producers – adulterated the product which stung the judges and left the American representatives in a sticky situation. As Canadian honey was especially well received, this generated buzz for their beekeeping techniques, honey harvesting, and preserving methods. A clipped text from the British Bee Journal noted, "Leading British bee-keepers speak of the quality of our honey in glowing terms; English ladies, especially, seem to think it superior to the ordinary production to which they are accustomed." The article went on to note, "Almost every day many bee-keepers visit us, watch our mode of disposing of the honey and examine our packages, they are convinced that we are popularizing the use of honey and in future the quality consumed will be much greater than heretofore." [4]

To meet the demands of an English market, however, Canada needed a great many new apiarists to swarm into the trade and produce honey at a standard fit for a queen, as outlined by the Canadian Bee Journal. Expanding readership and giving readers the tools to get started might have been part of Jones’ method to meet that requirement.

What is clear from reviewing this trade periodical is that at the time, Ontario honey production was very much in its early development stages. However, production leaders like Jones were eager to expand into markets across the Atlantic. Trade periodicals offer a unique perspective for understanding different viewpoints of the people involved in a given industry and the difficulties they faced in terms of markets, technology, and labour. Offering everything from legal insights to reviews of the latest tools and techniques, trade periodicals can help reveal the challenges and ambitions of a particular association and people within a given trade or industry.

As for me, I should buzz off and get back to the research and writing. Busy bees make honey.

Sources:

- “Greetings,” Canadian Bee Journal vol. 2, no. 34 (November 17, 1886): 2.

- “Premium List,” Canadian Bee Journal vol. 2, no. 34 (November 17, 1886): 664.

- “Canada at the Colonial,” Canadian Bee Journal vol. 2, no. 34 (November 17, 1886): 666.

- “Canada at the Colonial,” Canadian Bee Journal vol. 2, no. 32 (November 3, 1886): 626.