Long-term legacy for short-term memory

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

Molly Gatt

Algonquin College Journalism Program

In the film, 50 First Dates, Adam Sandler had to win the heart of Drew Barrymore every day because due to an accident, she suffers from amnesia and can’t remember what happened the day before.

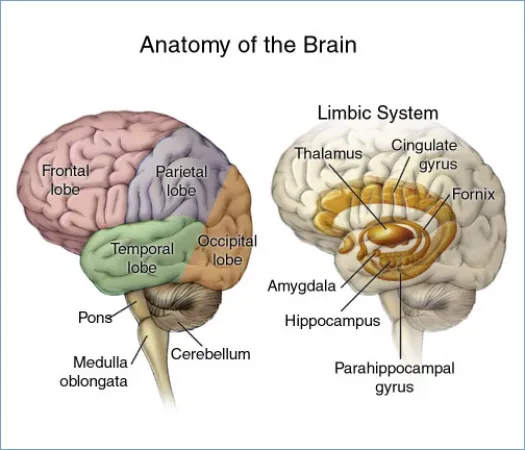

Brenda Milner, a British neuroscientist who immigrated to Canada, had a similar, but real life experience studying a patient for 30 years who never remembered her. Her patient, Henry Molaison, had surgery to reduce his seizures, but the surgeon removed his hippocampus and he lost his ability to turn short-term memories into long-term ones. Milner’s research would discover, among other things, that the hippocampus was essential for making memories.

While memory loss has been used as a plot device in comedies such as 50 First Dates, for Milner, her time with Molaison changed the way neuroscientists understand the mind’s ability to remember. Milner also discovered that the mind has different storage units for different kinds of memories. Memories of language and body movement have their own space inside the brain.

Milner’s long-term research with Molaison created the field known as cognitive neuroscience, which is a combination of neurology and psychology. Because of her meticulous nature, Milner is credited as one of the best neuroscientists of the 20th Century. She attributes her success to her sharp eye and curious mind. Milner was promoted to Companion of the Order of Canada in 2004 – the highest honour within the Order.

Milner was inducted into the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame in 2012.