Charting unchartered territory in neurosurgery

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

Ilana Reimer

Algonquin College Journalism Program

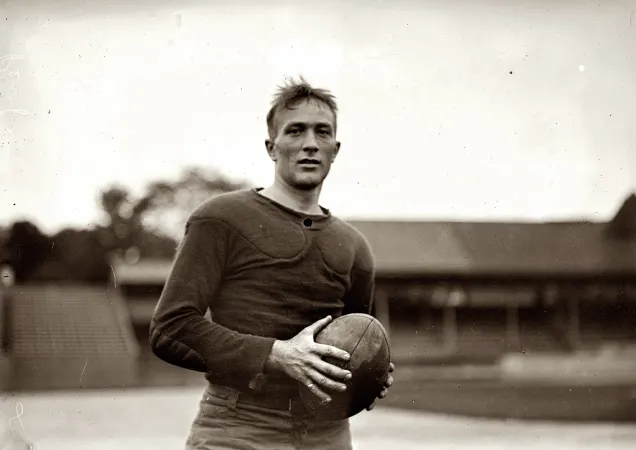

Wilder Penfield was determined to enhance the practice of neurosurgery. He considered it a terrible profession, admitting in 1921 that if he didn’t think the career was improving, he would hate it. But Penfield could not help being fascinated by the human brain, and his work completely changed our knowledge of the organ.

Originally from the U.S., Penfield was recruited to become a professor of Neurology and Neurosurgery at McGill University in 1928. Six years later he opened the Montréal Neurological Institute, where surgeons and scientists could work together to research, diagnose and attempt treatments for brain illnesses. He became a Canadian citizen the same year.

Penfield also began improving and expanding upon a bold surgical tactic he’d learned from his German mentor, Otfried Foerster. Known as the “Montréal Procedure,” the steps were delicate and required a high amount of trust on the side of the patient. With only a local anesthetic, the patient remained awake and described their reaction while the surgeon probed different areas of the expose ;brain tissue.

Using the patient’s feedback, Penfield looked for the scar tissue that causes epilepsy. The procedure also allowed Penfield to discover the functions of previously unmapped areas of the brain. He found that stimulating the temporal lobes invoked clear memories, and even located the place in the brain where dreams are stored.

Penfield was acknowledged nationally and internationally for his innovative work, but his goal was always grounded in the desire to make his patients’ lives better. “Wilder Penfield was not only a great surgeon and a great scientist,” said George Pickering, a Regius professor of Medicine at Oxford University, “He was an even greater human being.”

Penfield died in 1976, and was inducted into the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame in 1992.