The Dominion Observatory's Many Functions, part 3

The Dominion Observatory's Many Functions, part 3

by Randall Brooks

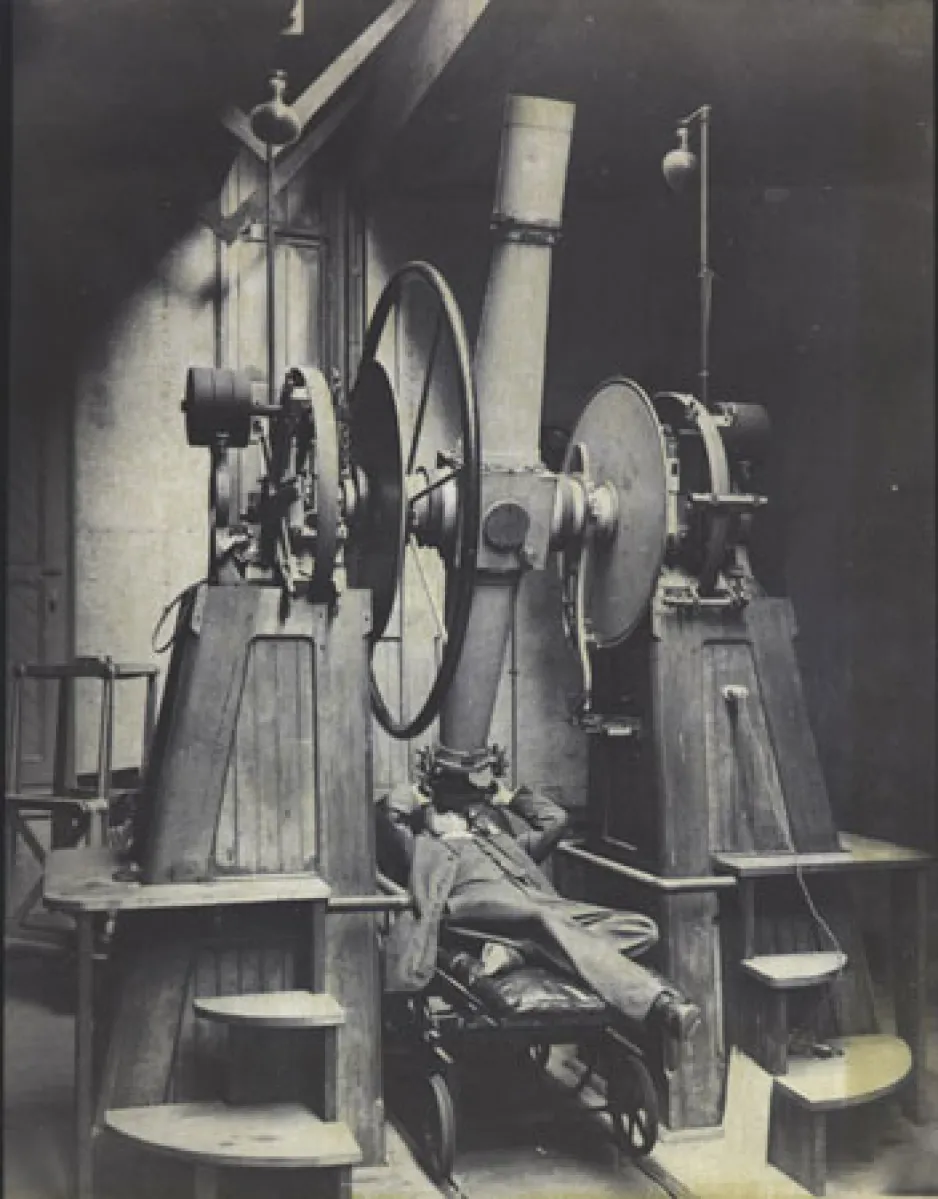

J.S. Plaskett illustrates the observing position at the meridian transit instrument, ca 1913–1916. The instrument was positioned precisely on Canada's prime meridian, in the transit room of the Dominion Observatory.

The Determination of Time

The key responsibility in the early years was time determination. This required the use of a type of telescope called a transit telescope, whose motions were limited to the meridian - the imaginary line drawn through the sky, from the southern point on your horizon, through the point directly overhead (called the zenith), to the northern point on your horizon.

Until the early 1930s, the meridian circle transit (at left) * was the primary instrument used to measure the time at which stars passed across the meridian. Astronomers then regulated time on a sidereal self-winding clock made by Sigmund Riefler**. These times were compared to measurements made at Greenwich, Washington, and elsewhere, to define time in Canada, and then Canadian time signals were distributed via telegraph wires around Ottawa, to the railways and to other government observatories from Saint John to Victoria.

* The so-called meridian circle transit (above), from the early days, was destroyed when the Observatory closed in 1970. Only photographs of it remain. The Museum has one of the original transit telescopes - see part 2, artifact no. 1976.0300.

** The Museum's Riefler clock, artifact no. 1966.0545, was purchased at the same time but came from the observatory in Saint John, New Brunswick.

Sidereal Clock, 1904, S. Riefler, Munich, Germany. Sigmund Riefler’s precision sidereal clock. The pendulum was maintained in a slight vacuum and given a periodic pulse by an electromagnet. The most accurate type of clock available from 1891 to ca 1928, such clocks had a precision of 0.015 second per day. Source: Energy, Mines Resources Canada / Saint John Observatory, Artifact no. 1966.0545

Interest in the Sun

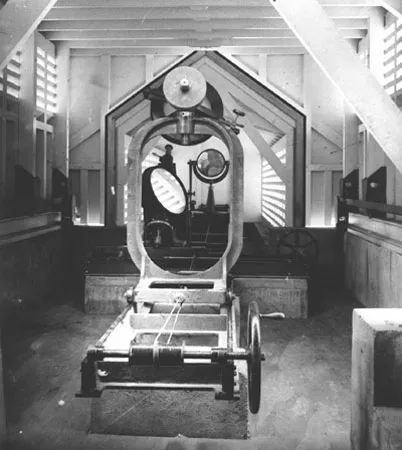

Otto Klotz’s interest in the Sun was accommodated by the purchase of a coelostat, a telescope designed to track the Sun.

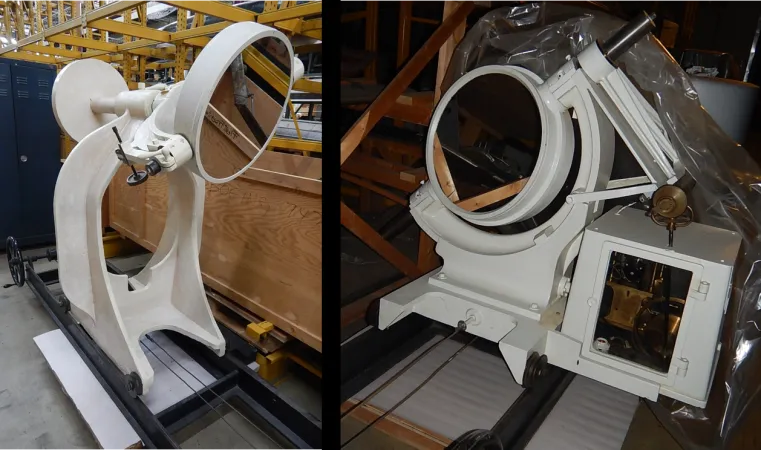

The Observatory's Coelostat, about 1905

Manufacturer: J.A. Brashear Co. Ltd.,

Allegheny, Pennsylvania

Artifact no. 1966.0402

The coelostat allowed astronomers to study the Sun’s composition by studying its spectrum, and to study sunspots by taking frequent photographs of the Sun each clear day.

This instrument was taken to Labrador on the Canadian Eclipse Expedition 1905 (see photos below).

The coelostat set up for the 1905 total solar eclipse in Labrador. The expedition was chronicled photographically by J. S. Plaskett in a photo album which survives today.

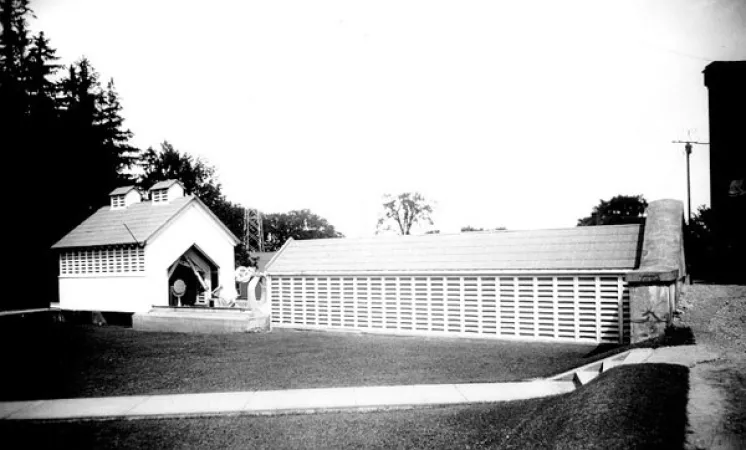

The Coelostat Shed at the Dominion Observatory

Back in Ottawa, a specially designed shed with roll off sections housed the coelostat for almost seventy years. From 1905 the Dominion Observatory’s astronomers made notable contributions to the study of the Sun, an aspect of Canadian astronomy that continued with new instruments, both optical and radio, until 1993 when the last of the solar programs ended.

By analyzing a series of photos (below) taken with the coelostat in the 1930s, Dr. Ralph DeLury, an astronomer at the Dominion Observatory discovered that the Sun rotated at different rates at different latitudes from the solar equator: the higher the latitude, the more slowly it rotated.

The Studies of Stars at the Observatory

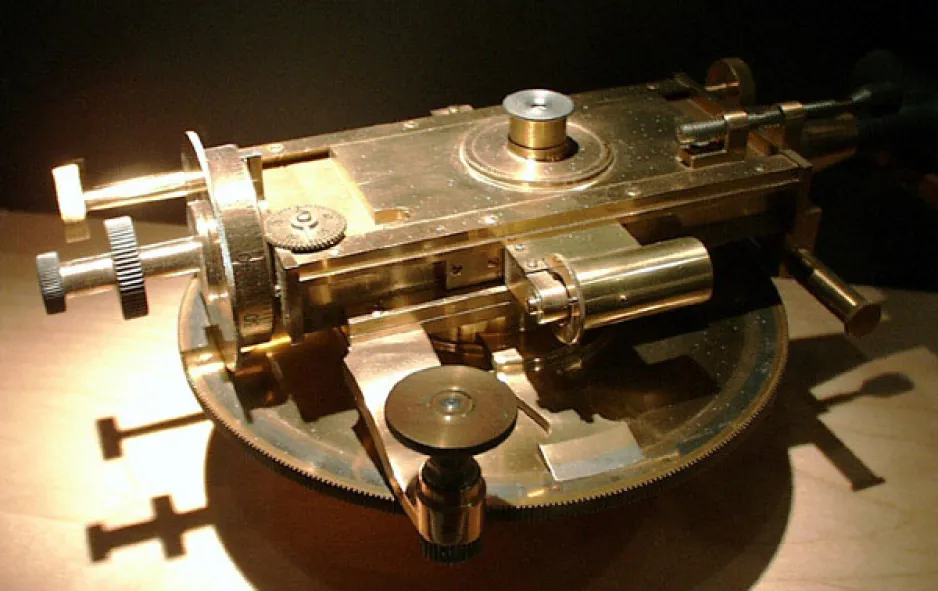

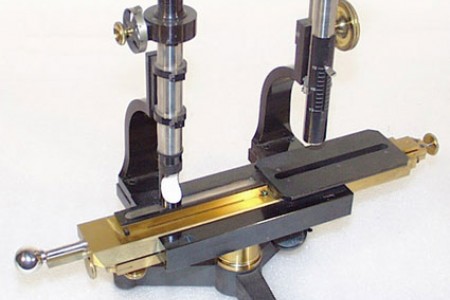

A Filar Micrometer Measures the Separation Between Double Stars

Manufacturer: Warner & Swasey,

Cleveland, Ohio

Artifact No. 1970.0212

One of the studies of stars at the Observatory measured the motion of one star around another in binary or multiple star systems. A filar micrometer attached to the 15-inch telescope for this work, but the astronomers soon became much more interested in the physics, or astrophysics, of the stars and nebulae (gaseous clouds or galaxies).

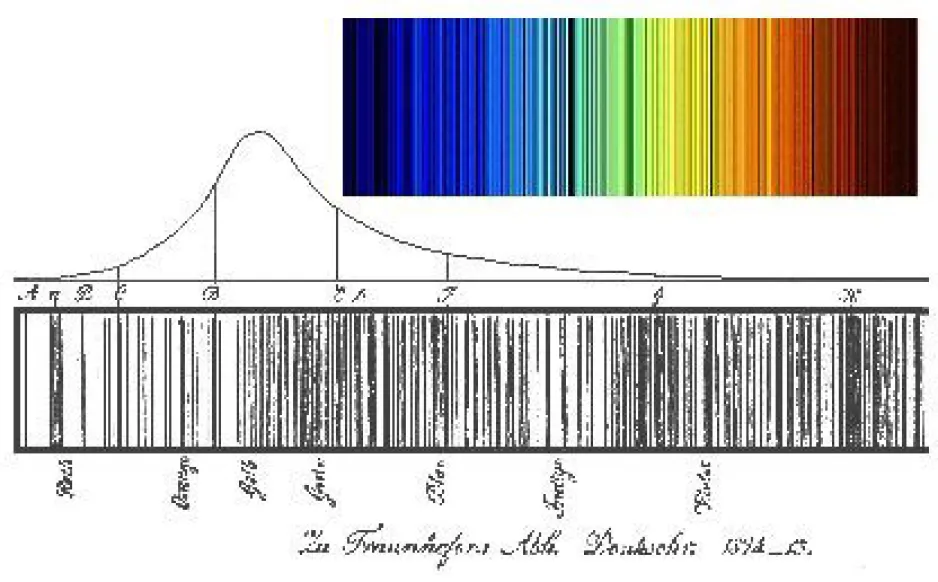

Spectroscopic Investigations

Two aspects of the spectroscopic investigations were most significant. Stellar spectra show lines (a sort of cosmic bar code) that vary from star to star, and can vary over time within one star’s spectrum. The positions of these lines, compared to a set of standard, known lines, indicates the star’s composition, and whether it is moving towards or away from Earth through a process referred to as Doppler shifts.

The spectrum of the Sun as first drawn by Joseph von Fraunhofer, ca. 1815.

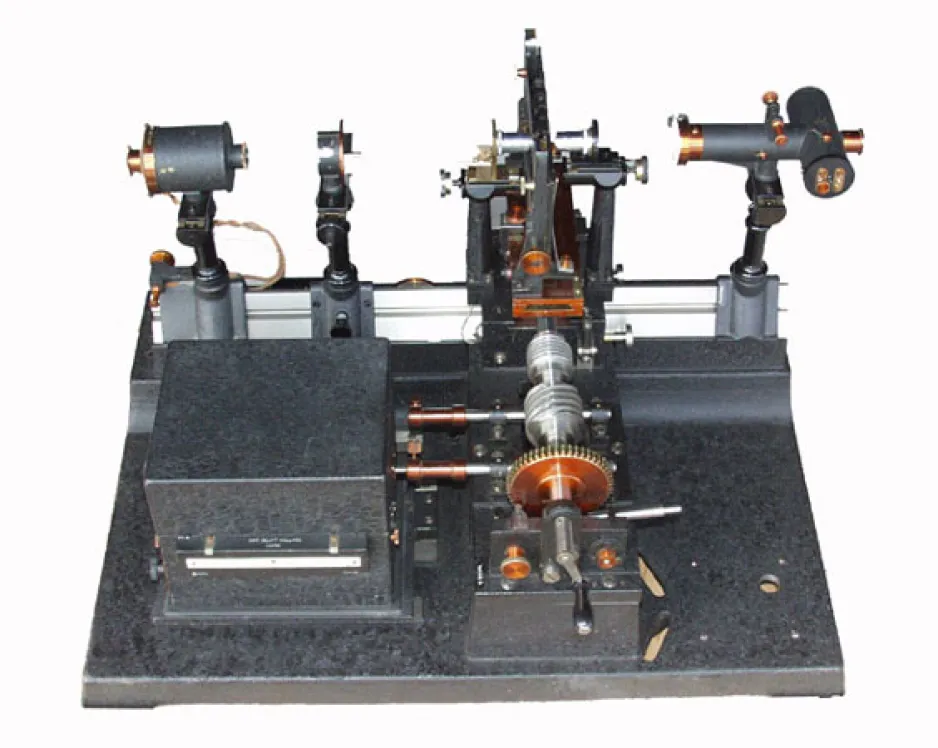

A prism spectrograph attached to the 15-inch (38-cm) telescope was used to photograph the spectra of stars for classification and for measurement of velocities of double stars, ca 1930.

A Spectrograph Breaks Up Light to Study the Composition of the Sun and Stars

The studies of the composition of the Sun and stars require an instrument called a spectrograph.

These early instruments used several glass prisms to break up and spread the light of the object. A camera on the spectrograph recorded the spectrum for later investigation.

Depending on the brightness of the star or nebula, an exposure lasted a few minutes to hours. The clock drive of the Observatory's 15-inch telescope was critical, as it moved the telescope to compensate for the Earth’s daily rotation.

Toepfer measuring engine, artifact no. 1970.0214

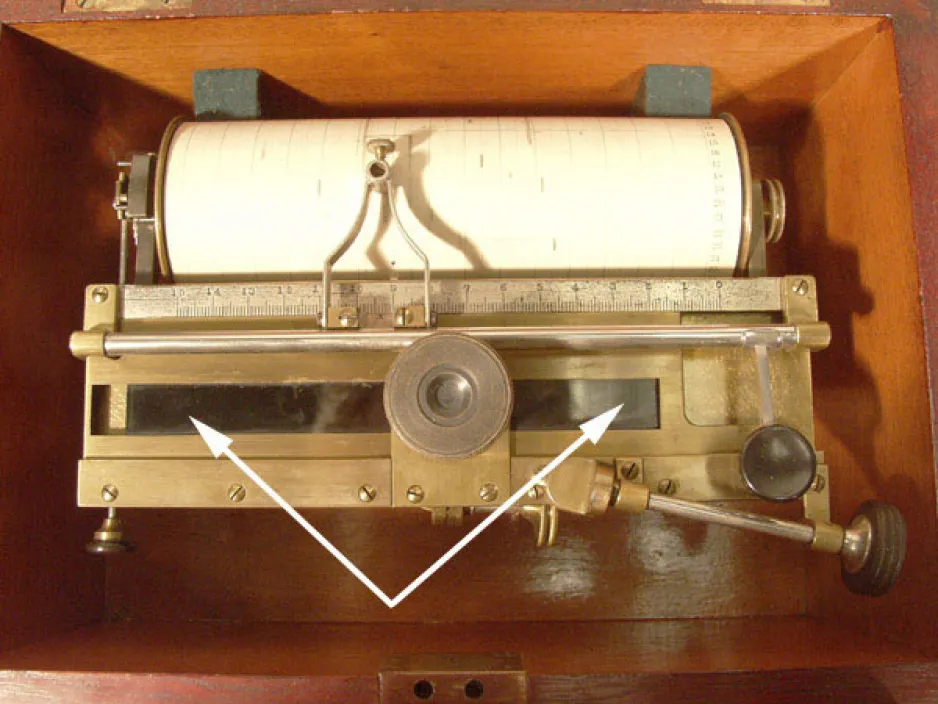

The Measurements of Spectral Lines were Taken with a Measuring Engine, 1904

Manufacturer: Otto Toepfer & Sohn,

Potsdam, Germany

Artifact no. 1970.0214

The very fine measurements of these spectral lines were taken with a measuring engine, and the Museum has three of the Dominion Observatory’s early engines. These were made by the German firms of Toepfer (1970.0214, 1970.0221) and Zeiss (1970.0222).

Photographing the Stars and Measuring Their Brightness

A double astrograph (a telescope with two cameras) was added at the Dominion Observatory in 1915, and mounted in the Photo Equatorial Building adjacent to the observatory. It was intended to photograph clusters of stars and to allow astronomers to measure the brightness of the stars on the photographs with an instrument called a photometer. One of the astrograph cameras has a thin wedge-shaped glass prism in front of it. This allows simultaneous photographs of the cluster stars and their spectra. This extra feature of the astrograph required that one of the telescopes be adjustable in the direction it was pointed, compensating for the fact that the telescope with the prism viewed a field of stars off axis from the direction the astrograph was pointed. With the photographs and spectra astronomers were able to discover variable stars, and used the information to establish the distances to nebulae and to clusters of stars.

Double Astrograph, about 1912

Manufacturer: J.A. Brashear Co. Ltd.,

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Artifact no. 1966.0401

The double astrograph has two main cameras plus a patrol camera. The camera with the cap lifted has the thin wedge-shaped prism in front. The smaller telescopes are for finding the objects to be photographed, and to track the objects during the long exposure times.

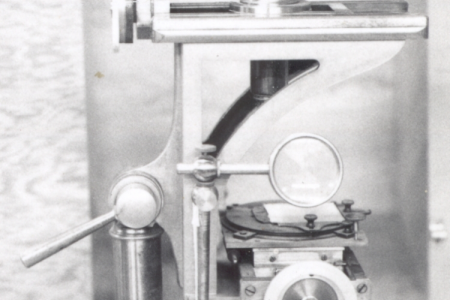

Photometers Measured the Brightness of Stars

Photometers were used to measure the brightness of stars from the photographs taken with the Brashear astrograph. The Museum has two photometers, one by Warner & Swasey (1970.1516) and a later one by Kipp & Zonen (1970.0213).

Warner & Swasey wedge photometer

Photometer, before 1929

Manufacturer: Warner & Swasey,

Cleveland, Ohio

Source: Energy, Mines and Resources Canada

Artifact no. 1970.0516

This is a wedge photometer. The long black strip seen in the photograph is a photographic “wedge,” which varies in density from end to end. The observer physically adjusted the position of the eyepiece until the star just disappeared. The position on the chart indicated the brightness of one star compared to others—a combination of stars of known and unknown brightnesses.

The the Kipp & Zonen photometer.

Photometer, before 1929

Manufacturer: Kipp & Zonen,

Delft, Netherlands

Source: Energy, Mines and Resources Canada

Artifact no. 1970.0213

The later photometer, the Kipp & Zonen, was a type that employed the photoelectric effect discovered by Einstein in 1905. A light was projected through the negative of a photograph of stars onto a photosensitive tube. An electric current was thus created, which was proportional to the amount of light it received, and this indicated the brightness of the stars being measured on the photograph, one by one. The analysis process requires meticulous attention to a variety of effects and possible errors.

The Dominion Astrophysical Observatory National Historic Site of Canada

Over the first few years of the Observatory’s operations, its astronomers, John Plaskett in particular, soon had a vision to expand the Observatory’s scientific studies. Plaskett wanted a very much larger instrument and he persuaded the Canadian government to fund a new observatory with what was to be the world’s largest telescope.

The Dominion Astrophysical Observatory was built in Victoria, British Columbia. When completed in 1917, the 72-inch (183-cm) reflecting telescope was the largest in the world but remained so for only a few months into 1918. The First World War had delayed its completion, as the 72-inch (183-cm) mirror was to have been made in Belgium, near the centre of the conflict. Under Plaskett’s leadership, Canada became a leading centre for astrophysical studies, a position it still holds.

Additional Readings

Canada's Historic Places: The Dominion Observatory

Arthur Covington, A Zenith Telescope of Historical Interest, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol. 55, No. 6, 1961.

John H. Hodgson, The Heavens Above and the Earth Beneath: A History of the Dominion Observatories, Part 1, To 1946, Energy, Mines and Resources Canada, 1989. Download Part 1 here.

John H. Hodgson, The Heavens Above and the Earth Beneath: A History of the Dominion Observatories, Part 2, 1946 to 1970, Energy, Mines and Resources Canada, 1994. Download Part 2 here.

Richard Jarrell, The Cold Light of Dawn: A History of Canadian Astronomy, University of Toronto Press, 1988.

Otto Klotz, The Dominion Astronomical Observatory at Ottawa, Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol. 13, No. 1, 1919.