McGill-Ingenium Fellowship: Part Two - A Tale of Two Nations: Birth Control in India and Canada (1930–60s)

Two Sides of the Same Coin

On a sticky February afternoon in 1936, Margaret Sanger, an American birth control advocate, attended the first All-India Population Conference held at the famous Cowasjee Jehangir Hall in Bombay (present day Mumbai). The conference was attended by the wealthy of Bombay society, the who’s who in the field, as well as doctors, advocates, government officials, and more. At around the same time, family planning societies began to emerge in India. These societies promoted birth control and advised women who visited their centres about possible birth control techniques. Varied as the organizations were, they shared the common goal of insisting that poor women use birth control products to control reproduction.

In present times, feminist groups have furthered campaigns for contraception access for women in a fight for reproductive freedom. However, initial discussions around birth control were prompted by fears of overpopulation. The role of reproduction in population control first appeared in English economist Thomas Robert Malthus' 1798 paper titled “An Essay on the Principle of Population.” In this work, Malthus suggested restricting who could and could not marry based on certain desired qualities. His ideas went on to inform Neo-Malthusianism theory which suggested contraception was an essential means of population control. Later, in 1893, informed by these ideas, Francis Galton coined the term ‘eugenics’, which referred to the control and selective breeding of people to improve humankind. In other words, by the turn of the twentieth century, anxiety about population growth saw contraceptive advocacy spearheaded by neo-Malthusians and eugenicists, many of whom were men. In this way, Malthus’ theories were re-conceptualized as birth control advocacy—at both national and global levels. This foretells the problematic and less-than-feminist beginnings of modern birth control.

Here, I discuss the stories of two nations, India and Canada. Their histories converge and diverge in noteworthy ways.

There are parallels between the two nations in terms of the intellectual and material trajectories. Both nations, as in the case of other colonies, saw debates surrounding birth control argue for its advocacy, for eugenicist reasons. In terms of the ground level material realities, vulnerable women in both nations needed birth control owing to grim maternal and infant health. Notably, where the nations diverge is in terms of the nature of products available and, indeed, in the free choice of purchase and use, available in India, and not so in Canada (until 1969). The complexities of both stories are as interesting as they are unsettling.

Tensions Between Need and Access

In Canada, concerns around the cost of having large families and poor maternal and infant health grew in the years following the Great Depression of the 1930s. Through the 1940s and 1950s, the use and sale of birth control was illegal and punishable under the Criminal Code of Canada, however, diaphragms and pessaries were available to Canadian women through physicians, and condoms were sold at drugstores as prophylactics against disease. It was only in 1969, about ten years after the birth control pill went on the market in the United States, that Canada’s parliament passed Bill C-150. This Bill, among other things, decriminalized birth control (including voluntary sterilization) and abortion (if approved by a hospital’s therapeutic abortion committee).

Even so, birth control advocates, such as Alvin Ratz Kaufman, saw contraceptives and sterilization as a method of controlling Indigenous and working-class communities. In eugenicist language that bore an uncanny similarity to that of many birth control proponents in India, Kaufman sought to regulate the reproduction of the “unintelligent” and “feeble minded,” not the least directed at Indigenous women. In other words, the early campaign for birth control in the first half of the twentieth century in Canada saw a tense and uneasy relationship between material realities of women’s health and the dubious ideology that supported birth control use and access.

Bleak Reality and Rhetoric

Canadian historian Erika Dyck has well argued in her work that maternal and infant health was bleak particularly amongst Indigenous communities that had the least access to healthcare. Similarly, in India too, sections of society that were most vulnerable, such as lower castes, rural and working communities, had the grimmest maternal health as well as limited access to healthcare resources.

As these images reflect, infant mortality rates in India were gloomy compared to other countries, and those communities in India that were most vulnerable, such as the Scheduled Castes, had the poorest infant health compared to advantaged communities, such as the Parsees and Europeans within India. Indeed, the need for birth control stemming from legitimate concerns of poor health of mother and child, and loss of life due to multiple pregnancies, had an uneasy relationship with the language and proponents that surrounded its advocacy.

Indian advocates of birth control, much like their Western counterparts, revealed their fears and spoke in disparaging tones about the poor sections of Indian people. One such example was P. K. Wattal, a Kashmiri Brahmin who, in 1916, published an influential book, The Population Problem in India: A Census Study. His concerns were quite simply, eugenic. He believed that there was an unchecked increase of the poor and unfit, and that the Indian racial stock was in decline. The 1933 edition of his book included the results of the Census of 1931 to support his argument. Wattal raised fears about the high fertility of those he considered poor racial stock such as tribal communities, lower castes, and Muslims.

Similarly, popular Indian leader Subhas Chandra Bose, in his presidential address to the Congress in 1938 said:

“With regard to the long-period programme for a free India, the first problem to tackle is that of our increasing population. I do not desire to go into the theoretical question as to whether India is over-populated or not. I simply want to point out that where poverty, starvation and disease are stalking the land, we cannot afford to have our population mounting up by thirty millions during a single decade… It will, therefore, be desirable to restrict our population until we are able to feed, clothe and educate those who already exist. It is not necessary at this stage to prescribe the methods that should be adopted to prevent a further increase in population, but I would urge that public attention be drawn to this question.”

Despite the emphasis on curtailing population, the leadership of the time did not, in the least, concern themselves with the what types of contraception should be used. This is where the story gets most interesting. It begs the question: what birth control products were available in India and Canada during these years?

Markets and Experiments in Contraception

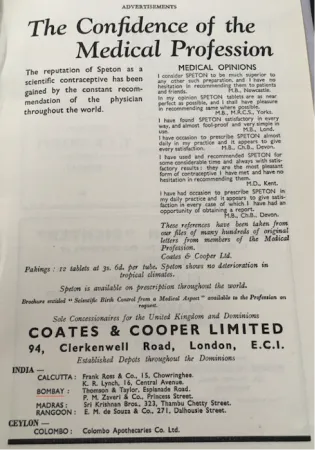

By the early 1930s, several kinds of contraceptives had entered the Indian markets. Products such as condoms, diaphragms, tonics, birth control pills, foam powder, jellies, and chemical contraceptives were being manufactured and sold. Manufacturers were both Indian and foreign, from large and small firms; no single product dominated the sexual health market. For the next 30 years, the market and affiliated medical personnel served as advocates for birth control products in India. The medical fraternity in India, as well as local and global champions of birth control, showed flexibility in their interpretations of women’s health—that is, it was not their first concern.

The birth control market was a private one based on profit. The manufacturers based in London, New York, Tokyo and Berlin, and retailers based in Bombay, Delhi, Calcutta and Kanpur—whether local or global—overlapped in their promotion of these products as “modern” and “scientific.” They understood the demand for birth control products, and the appeal of science-based terminology as a marketing strategy, in the Indian market.

Research budgets, staff and the development of new products grew steadily in the 1920s and 1930s. There was the emergence of dedicated research institutes catering to the pharmaceutical industry. Examples of these are the Merck Institute for Therapeutic Research founded in 1933, the Lilly Research Laboratories founded in 1934, and the Squibb Institute for Medical Research and the Abbott Research Laboratories founded in 1938. Research in the pharmaceutical industry increased manifoldly after the Second World War. Annual spending on research on the US-based pharmaceutical industry reached about $50 million by the early 1950s and quadrupled by the 1960s. Despite the pharmaceutical standards, contraceptives in public circulation were largely experimental in nature with little or no quality control.

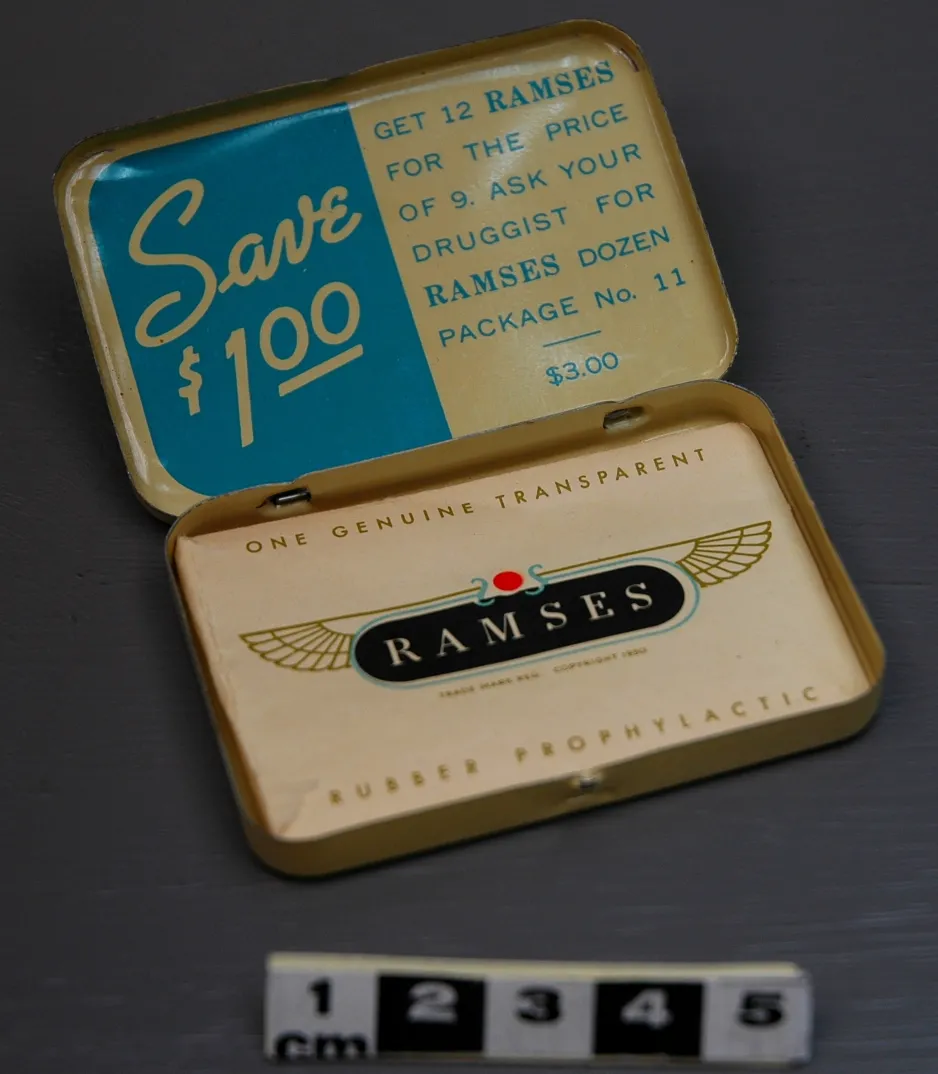

Notably, prior to 1969, sponges, pessaries and caps entered the medical field in Canada but not for their contraceptive properties. Sponges, for example, were recommended to realign the angle of the uterus, and condoms, rather than being advertised as contraceptives, were sold as prophylactics against disease. Also, most interesting is that Julius Schmid, creator of the Sheik and Ramses condom, who was born in Germany and later immigrated to New York, used Egyptian and Arab names and imagery on much of the packaging to signify strength and masculinity. The name Ramses comes from the third pharaoh, Ramesses, remembered as the most powerful and glorious leader of the ancient Egyptian dynasty.

Similarly, pessaries, prosthetic devices that could be used by women as contraceptives, bring a fascinating story. Originating from the ancient Greek word ‘pessós’, they are mentioned in the oldest surviving copy of the Hippocratic oath that stated– “Similarly I will not give to a woman a pessary to cause abortion.” In Canada, the use and sale of pessaries from the 1930s onwards strings together not only manufacture and distribution in an international way, but also advocacy. This is because, on the one hand, these devices were often manufactured in the US and elsewhere, with local retail and supply, and on the other hand, early advocates of birth control travelled as “medical missionaries” to other countries to promote them. In the case of the pessaries seen in Figures 10 & 11, Canadian medical doctor, Dr Norman Found, promoted them when he worked as a medical missionary in Korea from 1921 to 1935. It may be speculated that Canadian companies, in this case Julius Schmid Canada Ltd, promoted their own brand internationally through such missionary work– given that the brand names were highlighted clearly on many of the products, and since it was not yet legal to promote birth control in Canada.

Choice, But What Kind?

Canada’s history with birth control saw the forced sterilization of Indigenous women. Different yet similar, in India, birth control was portrayed as the way out of poverty and therefore imposed upon poor women. Aside from that, since Canada criminalized the use of birth control, there was not the same option of choice and preferences that women in India had because of the large birth control market that offered several products. Indeed, in Canada birth control in these early years primarily meant condoms used by male consumers, or sterilization. This is different from the story in India where the sexual health market catered largely to women users. Birth control products in the Indian markets from the 1930s onwards were essentially female contraceptives (other than the condom).

This difference of who was using the contraceptives in India and Canada, as well as the choices available in India, makes the story of the two nations in this time period interesting in their contrast. Even so, the matter of choice in India came with significant tensions. As mentioned, many contraceptive technologies that entered the Indian markets had questionable efficacy and safety even as they were aggressively promoted by Indian and non-Indian advocates.

One such bizarre product was promoted by Alyappin Padmanabbha Pillay, the man considered India’s foremost advocate of birth control. A regular correspondent of Western eugenicists, Pillay hosted Sanger when she visited Bombay. He was also the founder and editor of the international scientific journal Marriage Hygiene, which aimed to “publish scientific contributions treating marriage as a social and biological institution.” In 1960, Pillay wrote a book in English titled Birth Control Simplified: 51 Illustrations, 10 Diagrams, 4 Tables. In the book he wrote about contraceptive options for women and argued that foam powder was “the ideal contraceptive.”

In Pillay’s discussion of foam powder, far from providing readers with information, he made fanciful statements about female orgasms. He wrote, “The difficulty with the (foam) tablet is that there must be moisture in the vagina for it to disintegrate and diffuse. Often the vagina is dry naturally or because of insufficient sexual stimulation.” He elaborated saying, “During orgasm of the woman, the quantity of fluid in the vagina increased. The longer the coital time, the greater the disintegration of the tablet and other chemical contraceptives. These two are important factors in the effectiveness of chemical contraceptives, (Pillay’s emphasis), that is to say, they are more effective when the woman gets orgasm and the coital time is long.”

Pillay’s claim was that the orgasm of a woman during sex is necessary for the success of foam powder as birth control. For the contraceptive foam powder to work as spermicide, he claimed, two conditions had to be met: first, the woman would have to orgasm during penetrative sex, and second, she would have to do so before the man ejaculates. Pillay’s confidence in the sexual abilities of men is inspiring; however, the chances of either of these happening were statistically low, and the chances of both, even lower. Therefore, the chances of foam powder working as an effective contraceptive were very poor. This was one amongst several kinds of substandard contraceptives that were being circulated. It may be argued that the sexual health markets emerged in response to the demand for birth control, however, they did not deliver in terms of quality or efficacy of product, even less so, towards women’s wellbeing.

Concluding Thoughts

In sum, the grim statistics regarding maternal and infant mortality and the incredible suffering of women due to multiple pregnancies indicates more than just the racist paternalism behind the early global contraceptive movement. Perhaps it is difficult and inaccurate to separate the intellectual and materials thought processes. The startling neglect of women’s wellbeing, particularly the most vulnerable, reflects the limits of the early contraceptive technology—even as it could provide the option to control the number of children women had to bear. It raises discussion about how a concern for women’s health played a role in the face of the rhetoric of overpopulation, and how the limits of such thinking were visible in the treatment meted out to women. Regretfully, in the tale of both nations in relation to early birth control, the larger structural and societal hierarchies were left uncontested.

The author is grateful to David Pantalony and Emily Gann for their valuable comments as well as assistance in navigating the virtual archives.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!