Lights! Camera! Personality! The Karsh of Ottawa Collection Profile

In 1997 Jerry Fielder contacted the then-director of the Collection and Research Division of the Canada Science and Technology Museum, Geoff Rider, with an offer of a donation. Each year the Museum receives several hundred offers from across Canada, yet Geoff immediately recognized that this was not an average proposal. Since 1979 Jerry had been a curator and an assistant to prominent Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh.

Yousuf Karsh with his camera during a donation ceremony at the Canada Science and Technology Museum, 17 April 1998

When, five years earlier, Yousuf and Estrellita Karsh closed down their Chateau Laurier studio in Ottawa and moved to Boston, they donated prints and negatives to the National Archives of Canada. Now, the photographer had decided that it was only appropriate to offer his studio equipment to the Canada Science and Technology Museum, and Jerry had been given the task of arranging the donation. On 17 April 1998 Yousuf Karsh presented the Museum’s chairman with one of his lenses—the lens that he used in 1941 to take his famous photograph of Winston Churchill. With this symbolic gesture, Karsh transferred the ownership of his photographic equipment to the Museum.

8×10 bellows Calumet, Karsh’s main camera, draped with a focusing cloth made for Karsh by his assistant and librarian Hella Graber

Despite the fact that he did not like to think about his equipment, or perhaps because he wanted to keep it out of mind, Karsh bought the best cameras that he could afford, designed to his specific instructions, and in fact he acquired and used a great number of photographic lights, cameras, and accessories.

Karsh’s camera cases bear witness to the photographer’s many travels, and to the wear that his equipment had to endure.

At the beginning of his career, Karsh carried with him around the world almost two hundred kilograms of equipment. His large Chrysler automobile was especially adapted to haul the cameras and lights: the back seat was removed and extra storage was installed on the roof.

The Karsh of Ottawa collection contains artifacts ranging from his cameras and lighting units to small accessories and retouching tools.

Finally, Karsh decided to maintain three sets of identical photographic equipment. One set was kept in his studio in Ottawa, a second was stored in New York, and a third set in London. The artifacts now held by the Canada Science and Technology Museum were used in Karsh’s Sparks Street, Chateau Laurier (both located in Ottawa), and New York studios, from the early 1930s until 1992, and many travelled with him around the world.

“To record the human spirit, human soul”

Karsh, The Searching Eye (Toronto: CBC, 1986)

Landscape, 1926. One of the earliest photographs taken by Karsh, this image won the $50 grand prize at a T. Eaton Company competition in 1926.

Yousuf Karsh was born in Mardin, Turkey, on 23 December 1908, to Armenian parents. The family left Turkey in 1922, and two years later, on New Year’s Eve 1924, Karsh arrived in Canada. Karsh began his study of photography at the studio of his uncle George Nakash in Sherbrooke, Quebec. There he learned to take, develop, and enlarge his first images, snapped with an inexpensive Brownie camera. One of Karsh’s landscapes won the grand prize of $50 at a local competition run by the T. Eaton Company.

John H. Garo, 1930, by Karsh

Nakash recognized potential in his nephew and in 1928 arranged an apprenticeship for Karsh with a Boston photographer and fellow Armenian, John Garo. Karsh was deeply affected by Garo’s art and his personality. Like his mentor, Karsh chose to learn the art of portraiture and become a photographer of the “giants of the earth.” To improve his skills, Garo encouraged the young apprentice to study great masters—Rembrandt, Rubens, and Velasquez.

A set of brushes given to Karsh by John Garo

At the end of his apprenticeship, Garo gave Karsh a set of brushes dating from 1890, which Garo had used to apply gum Arabic and bromoil to his prints. For the rest of his career Karsh kept the brushes locked in a safe and did not allow anyone else to use them. It was difficult for Karsh to part with this particular treasure, and the brushes were among the last objects that he passed on to the Museum.

Image from Saturday Night, credited “Karsh of Ottawa.”

In 1933 Karsh opened his own studio at 130 Sparks Street in Ottawa. The same year, at the theatre of the Ottawa Drama League (later the Ottawa Little Theatre), Karsh took the first photographs that gave him recognition. He submitted them to Toronto’s Saturday Night magazine. On 6 January 1934, the magazine printed photographs taken by Karsh in December 1933 at the Ottawa Drama League’s production of Romeo and Juliet. The images were signed “Karsh, Ottawa.” The Earl of Bessborough, who starred as Romeo, arranged for Karsh to meet his father Lord Bessborough, the first Governor General of Canada photographed by Karsh.

Lord and Lady Bessborough, 1933. The image was published in a double-page spread in the Illustrated London News.

Before he took the famous image of Churchill in December 1941, which opened the door to an exceptional career, Karsh spent almost a decade setting the stage for his art. He established his name as a skilled photographer, and became acquainted with important personalities, artists, publishers, and politicians. And most of all, he developed his own style characterized by masterful lighting, almost exclusive use of studio equipment, and careful development and retouching.

Foyer of the Ottawa Little Theatre, 1933; watching the illumination of the stage during theatrical productions at the Ottawa Little Theatre, Karsh became fascinated with artificial lighting, and began to experiment with the application of lighting units to photography.

Karsh found artificial lighting fascinating and challenging; he wanted to master it, and make it work for him. He was particularly interested in stage lighting, and learned new techniques watching his first wife Solange direct plays for the Ottawa Drama League.

The main studio lighting unit

The collection donated by Yousuf Karsh to the Museum contains seven lighting units from his studios in Ottawa and New York. The main lighting unit, the last used by Karsh in his Chateau Laurier studio, which opened in 1973, was produced in the early 1970s. The unit consists of a stand made by Dyna Lite Inc., a light box manufactured by Colortran Inc., and a Mylar diffusing screen. During a typical photographic session, the unit stood about one and a half metres to the right of the camera, and was placed slightly behind it. Karsh did not arrange the stage for photographic sessions himself. The equipment was always set up beforehand by the photographer’s assistant. First, the assistant checked all bulbs, and placed the main and fill lighting units in a standard arrangement. Then the assistant would assemble the backdrops. At the beginning of his career, Karsh used an old Canadian army blanket as a background for his images. He later purchased stands from the American Photographic Instrument Company Inc., and asked his technician and librarian Hella Graber to make several velvet backdrops, which he combined with homemade wooden or vinyl backgrounds.

Turban (Betty Low), 1936

When he photographed women, Karsh always used softer light and turned the main and fill units slightly away, directing the spot lights on the hair or shoulders to reduce the appearance of facial lines and wrinkles. If in the final results the subject still looked cold or unapproachable, and the personality that Karsh wanted to reveal was not reproduced by the camera, he would refuse to print the photo.

This 8×10 bellows Calumet was Karsh’s main camera.

The 8×10 bellows Calumet, made in 1956 in Chicago, was Karsh’s main camera. He used it for more than three decades, first in his Sparks Street studio, and then in the Chateau Laurier studio. For many years he took this camera or its New York twin across North America and to Europe. With the Calumets Karsh photographed Canadian prime ministers from Diefenbaker to Chrétien, as well as Ernest Hemingway, Mother Teresa, Margaret Atwood, Marc Chagall and many other personalities. Although Karsh took most of his pictures in 8×10 format, the camera had a removable back and could have been adjusted to 2×4 and 5×7 formats. The camera was painted a pale grey, almost white.

The focusing cloth made for Karsh by his technician and librarian Hella Graber

Karsh explained that “[a] camera need not look funereal.” Hella Graber made a focusing cloth, which Karsh liked to drape loosely over the Calumet. The cloth was sewn from rich burgundy velvet with a gold lining; Hella embroidered it with Karsh’s initials.

A Saltzman enlarger used by Karsh and his printer Ignas Gabalis

When Karsh moved his enlarger to the Chateau Laurier from his Sparks Street studio the ceiling had to be raised to accommodate the size of the machine. This extra-large enlarger allowed Karsh to make photographic prints up to 30×40 inches (76×101 cm) from the original 4×5 and 8×10 negatives. It took up to thirty minutes to print the photographs on this scale. Only Karsh and his printer, Ignas Gabalis, who worked with Karsh from the early 1950s until 1992, operated the enlarger. Because it took so long to produce the large format images, Karsh called Gabalis the world’s slowest printer, but admitted that the quality of his work was impeccable.

The glass blade, pencils, and magnifying glass used by Karsh to retouch his negatives and prints

Karsh processed negatives in batches of ten, in film developers made according to his own formulas. He used Kodak products to desensitize the film to a very low level of green light, and then used the light to inspect the film periodically as it developed until the negatives reached the density levels that Karsh desired, and could then be removed from the developing solution.

Karsh developed the photos on a Kodak paper called Opal V. He chose the paper carefully. It was perfect for portraits, as the texture of the paper was similar to the texture of human skin. Moreover, Opal V was coated with a matting agent containing very fine silica or starch, which shifted the light reflection from pure creamy-white to a tint of blue, making the portrait printed on this paper truly unique.

Karsh liked to do all the finishing work himself. His retouching tools included various inks, spotting colour sets, brushes, pens, and pencils, with Steadtler and Koh-I-Noor leads. Karsh employed these tools to soften and accentuate lines and shadows on prints. He also used a set of retouching Turquoise Prestomatic pencils; soft pencils produced a greater density of fine lines superimposed on each other, while harder pencils formed less visible light shading on the final prints. Among the retouching tools donated to the Museum is a custom-made glass blade with which he sharpened lines in negatives, a technique learned from Garo. When retouching photos, Karsh used a magnifying glass to examine the effects of his work. Karsh would allow Hella Graber and his assistants to help with some finishing work. For example, they lightly swept negatives with a polonium Staticmaster brush to remove the static, and after the photos were mounted, they cleaned them with a fine badger hair brush.

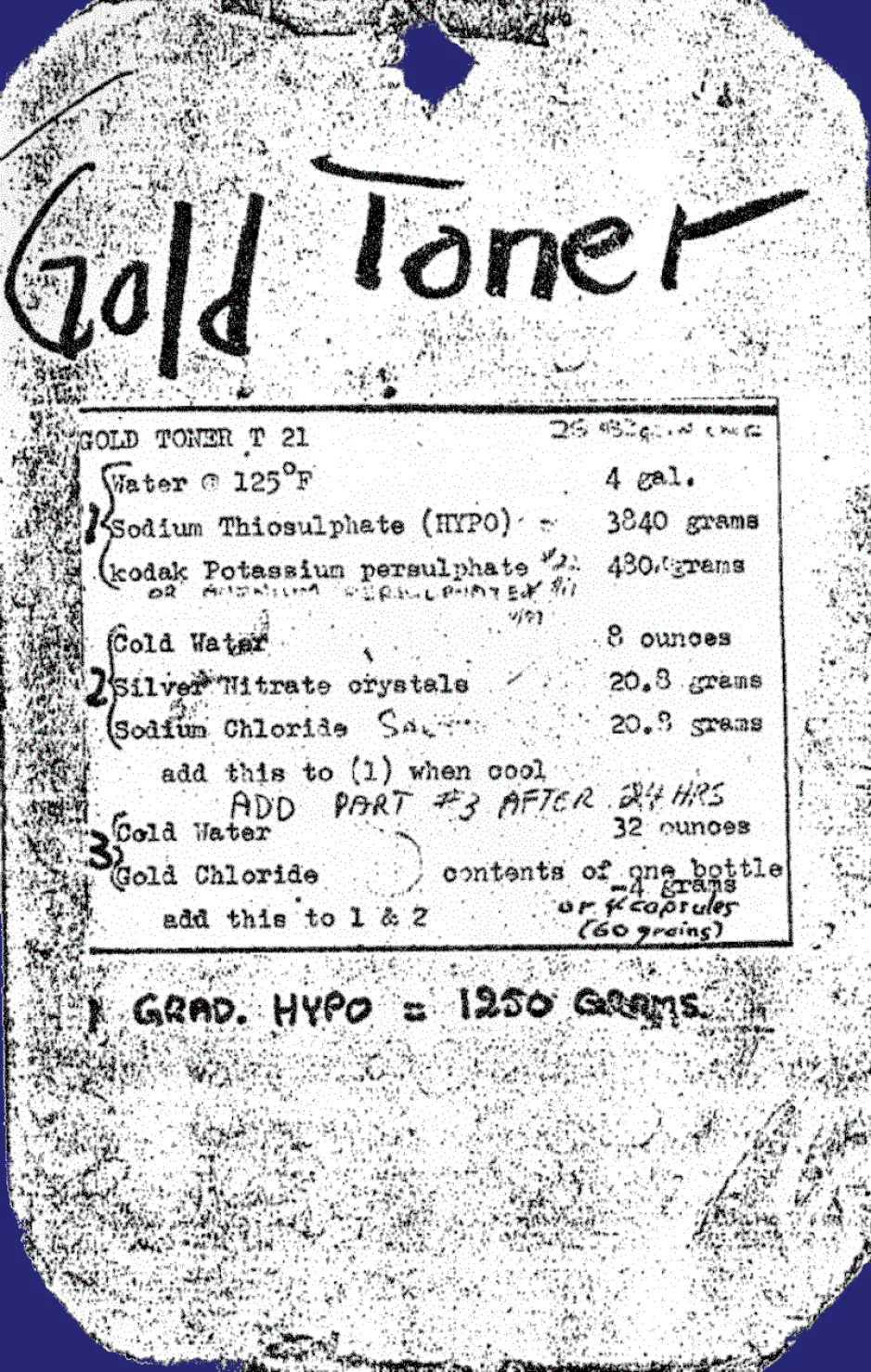

A copy of Karsh’s recipe for the gold toner with his handwritten notes

Assistants were also trusted with the task of mixing gold toner, made according to the master’s recipe, in a large stoneware crock. The gold toner was Karsh’s signature, as few photographers chose to use it. It was expensive and had to be applied at just the right moment to coat and replace silver salts, but the resulting gold-toned prints had a special warm and rich “archival” look.

The Karsh of Ottawa collection contains many other interesting tools of his trade: lenses, films, adapters, filters, light metres, and shutters. Along with the Museum collection of photographic trade literature, and behind-the-scene stories recounted by Jerry Fielder, Karsh's artifacts offer a glimpse into his now closed studios and darkrooms.